Burritt College

1848-1939

![]()

"Pioneer of the Cumberlands"

A History Of Burritt College

1848-1938

Marion West

Table Of Contents

Acknowledgements

Chapters 1: The Church of Christ And Nineteenth Century

Reform And Education

Chapter 2: Burritt College To The Civil War

Chapter 3: The Unstable Years: 1865-1890

Chapter 4: The Age Of The Phoenix: 1890-1918

Chapter 5: Sunset And Evening Star: 1918-1938

End Notes

Bibliography

Appendices

Appendix A: 27th General Assembly Of Tenn. - Burritt

College Incorporation

Appendix B: Incorporation Of The Church of Christ In

Spencer

Appendix C: Rules And Regulations Governing Burritt

College

Appendix D: Burritt College Courses Of Study For 1871,72

School Year

Appendix E: 29th Gen. Assem. Of Tenn., 1851,52 - Incorp.

Of Burritt College Philomathesian Society

Appendix F: Gen. Assem. Of Tenn. 1878 - Incorp. Of Burritt

College Calliopean Society

Appendix G: Literary Programs Of Burritt College

Well Known Christians Related With Burritt College

Timeline History Of Burritt College

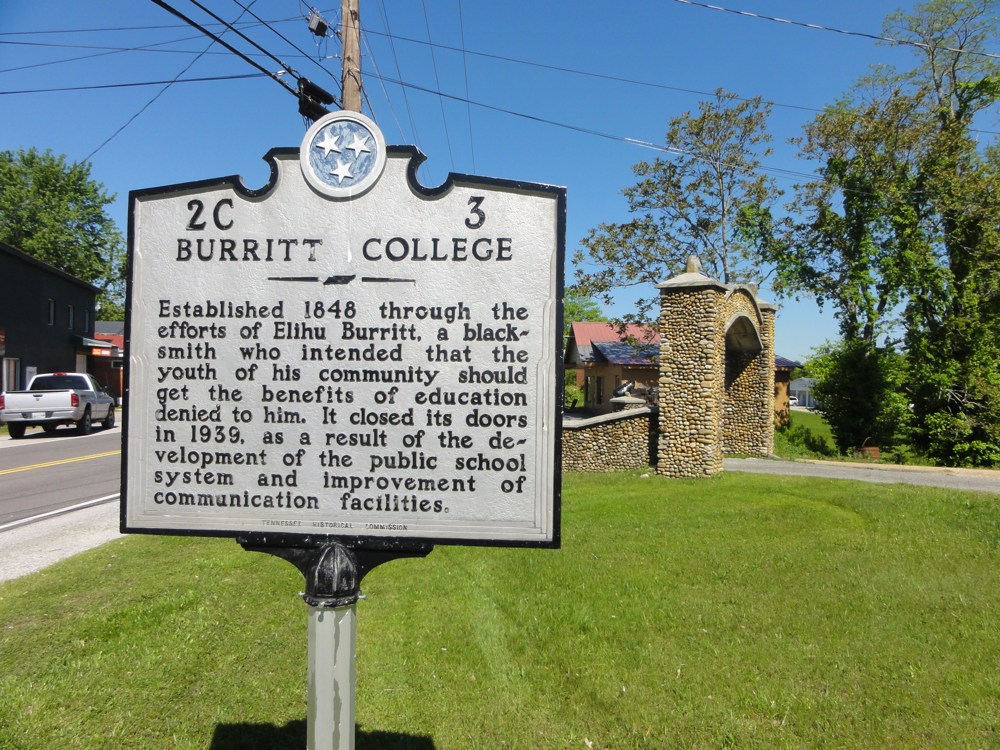

Historical Marker & Photos Of Old Burritt College

Directions To Spencer, Tennessee & Location Of The Remains

Of Old Burritt College Campus

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The undertaking of any project involving research and time requires much assistance on the part of many people. Cooperation on the part of those without whose help the materials could not be assimilated; counsel on the part of those whose experience qualifies them to give advice to the inexperienced; and patience on the part of all those in any way connected with the project are three qualities which are prerequisite to the successful conclusion of that project.

The writer wishes to express his grateful appreciation to the following persons for their cooperation in this project: first, Miss Mary Gillentine of Hollis, Oklahoma, for her lending the writer a number of original materials, without which this study would be incomplete. It is her wish that these materials be placed in the Burritt College Memorial Library at Spencer, Tennessee, for permanent keeping. The writer has complied with this wish. Secondly, Creed Shockley of Spencer, Tennessee, who gave so much needed assistance in revealing to the writer the local history of Burritt College and Van Buren County. His intimate knowledge of these areas proved invaluable in this study. Finally, Miss Mattie Cooper, research librarian at Tennessee Technological University, who cooperated so freely in complying with the writer's requests for rare and specialized studies unavailable locally, deserves a special word of thanks.

Remembrance is also made of the wise counsel and direction provided the writer by his graduate committee chairman, Dr. H.W. Raper. By his patience and advice the writer was able to complete this study. The assistance of the other members of the graduate committee, Dr. Nolan Fowler of the Department of History, and Dr. John Warren, of the Department of English, Tennessee Technological University, is gratefully acknowledged.

Special recognition is given to Mrs. John (Lois) Anderson of the Department of English, Tennessee Technological University, who, despite her very busy schedule, so graciously consented to proofread this paper. Mrs. Anderson's suggestions proved helpful in eliminating many incongruities in the mechanics of this paper.

CHAPTER I

THE CHURCH OF CHRIST

AND NINETEENTH CENTURY REFORM AND EDUCATION

The year 1848 was in many ways pivotal for both Western Europe and the United States. For Europe it was a time of political crisis and upheaval. Intense nationalistic feelings produced revolutions in Italy and Prussia, while there were also uprisings in Spain and Austria-Hungary. In this same year Louis Napoleon of France became President of the Second Republic following the flight of Louis Philippe from the country.

While Europe experienced political unrest, the United States was enjoying comparative calm. In January of 1848 gold was discovered in California; shortly thereafter the treaty ending the war with Mexico was signed, and later in 1848 Wisconsin became the thirtieth state in the union, a short time before Oregon was organized as a free territory. Thus the year 1848 was momentous for both Americans and Europeans in that it was a year in which economic expansion, political independence, and military conflict dominated the world scene. Although victory evaded the grasp of many of the liberal groups in Europe, 1848 was one of the notable years in world history.

For the people of the Cumberland mountain village of Spencer, Tennessee, the year 1848 was also a momentous one. The political ferment of Europe and even the events which were changing the political, economic, and geographic picture of America were very far away; however, an event more immediate and more personal commanded the attention of the citizens of the town. It was in the early months of 1848 that a small but influential group of Spencer's citizens made the decision to establish a college in the town.

The first idea concerning the possibility of establishing a college in Spencer is credited to Nathan F. Trogden, who was by trade a mason and a leading citizen of the village. Trogden had been contracted to erect a brick courthouse to replace the original log structure. It was while he was constructing this building that Trogden first thought about erecting a school for the children of the area. He conveyed his idea to John Gillentine, a native Virginian whose family was one of the first in the territory that later became Van Buren County.[1]

Trogden’s proposal was enthusiastically received by Gillentine and other leaders and resulted in a general meeting of the citizens from which a board of twenty-six, by Gillentine, was selected to secure a charter from the state and to set in motion the administrative machinery of the proposed school.[2]

The first order of business which the new board took up was the matter of raising funds for the purpose of erecting a building to house the college. Interested citizens of Van Buren, White, and Warren counties contributed a sufficient amount of money to warrant construction of the main structure.[3] Nathan F. Trogden was awarded the contract for the building. Trogden cut the timber for the edifice, hauled it to the site of the campus, dressed the lumber, and burned the brick, all virtually without help.[4] The building, a two-storied structure, was not completed in time to begin school in the fall of 1848; therefore, the opening was delayed until February, 1849.[5]

In selecting a name for the college the founders desired one which represented the ideals which they sought to embody in the school: scholarship, the dignity and worth of labor, and service to man.[6] The name finally chosen was "Burritt College," named for Elihu Burritt of Worcester, Massachusetts. The founders’ choice of a name has presented a number of intriguing questions that need to be answered before the study of the college itself is undertaken. These questions deal mainly with the nature of the religious group with which Burritt College was associated throughout its existence. Of special interest is the group’s views on social reform and education. In order to answer these questions it will be necessary to notice something of the nature and work of Elihu Burritt.

Elihu Burritt, commonly known in his lifetime as “the learned blacksmith,” gloried in the concept of self-improvement, and like many of his contemporaries, became a self-made man. Though a poor man with few opportunities for education, Burritt through initiative and determination acquired a working knowledge of approximately fifty languages. Even more outstanding in Burritt's own life was his ideal to serve mankind in some humanitarian endeavor rather than to accumulate a personal fortune, for "unlike most Americans, he had no ambition to rise above the working class from which he came.[7]

Burritt was born in New Britain, Connecticut, in 1810. At the age of twenty-seven he moved to Worcester, Massachusetts, where he was first exposed to the crusade against war, Burritt aligned himself with these peace forces and therein found his life's work. In 1844 he began the publication of a weekly newspaper, the Christian Citizen, which was to serve as an Organ for the peace movement until its demise in 1851. It was Burritt's work with this newspaper that first brought him to the forefront as a leader of the peace crusade.[8]

In 1846 Burritt went to England to enlist support for the peace movement. It was here that he first conceived the idea of a "league of universal brotherhood" whose object was "to employ all legitimate and moral means for the abolition of all. . .war throughout the world.” It was not long afterward that he succeeded in setting up this organization. Burritt was in Belgium establishing local chapters of the league in 1848, the year that Burritt College was chartered. These undertakings on the continent brought international fame to Burritt, and the response to his efforts was so great in Europe that he remained there until 1855, making only two trips back to the United States during this period.[9]

In addition to the Christian Citizen, which went defunct in 1851, Burritt also edited The Bond of Universal Brotherhood, an outlet for the parent league. Burritt served as co-editor of this paper with Edmund Fry until 1856. The most widely circulated of all Burritt's printed materials was the so-called Olive Leaves, a pamphlet which Burritt published periodically and sent to some 1,500 newspapers in the United States. A number of these pamphlets were sent to a few newspapers in Tennessee.[10]

Although Burritt's work in the peace movement in the Northeast contributed much to its success in this area, the work suffered in other sections of the United States. One of its weaknesses was the failure to carry its activities in to the South. By 1850 leaders in the peace effort felt that those most susceptible to the arguments of peace had been reached and because of this no concerted, effort was made to cultivate the support of sympathizers in either the South or West.[11] Until 1854 only a limited number of Burritt’s Olive Leaves, as well as periodicals of the American Peace Society, had circulated in the South. It was in this same year that the Reverend William Potter, an agent for the American Peace Society, toured Tennessee and Alabama and met with what he described as “a kind reception.” Although many of the citizens were "open to appeals, Potter wrote that "they were all practically unacquainted with the subject of peace."[12]

There are indications which run contrary to Potter's view that the citizens of Tennessee and Alabama were not familiar with the peace movement. In the first place, Potter himself admitted that the people were "open to appeals," therefore not entirely averse to the idea of pacifism. Secondly, Burritt himself felt there was sufficient peace sentiment in Tennessee to warrant a tour through the state on behalf of the American Peace Society in the mid-1850's.[13] Finally, that the founders of a college atop Cumberland mountain knew enough of the work and personality of Elihu Burritt to name a school after him indicates there was some degree of sympathy, if not outright support for the peace crusade.

A contributing factor to the existence of this sympathy in Tennessee lay in the presence of a large number of members of the Church of Christ, a splinter group which resulted from the "New Light" schism in the Presbyterian Church in the early years of the nineteenth century.[14] The nature of this group, as well as the loosely-knit organization[15] characterized the movement prevented any comprehensive unity on the moral and social questions of the day. Lacking my rigid organization, no one person or group could pronounce ex cathedra, the church’s official position on issues such as war, slavery, or education. Many of the more prominent leaders of this “restoration movement”[16] maintained the position that these were in the realm of human opinion upon which, in the absence of explicit instructions from the Bible, the church could not take a definite stand.[17]

Despite the abstinence by the church from social issues, many of the more influential leaders spoke out freely on the problems which faced the church in the nineteenth century. It should be noted, however, that this response was intended only to point out the Christian's relationship to them, and not because the leaders were interested in the problems for their political content.

An example of this response came from Alexander Campbell, the leader of the restoration movement in Pennsylvania and Virginia. In speaking on the issue of war Campbell pointed out that war was immoral because it was the result of rebellion against God. He also emphasized that Christians could not participate in war because they were pacifists, being followers of Christ, the “Prince of Peace."[18] Despite the fact that he did not actively participate in the peace movement of the time, Campbell nevertheless lent his moral support to it end used every method short of involvement to assist the effort. The Millennial Harbinger, Campbell's magazine, was used to reprint the articles of the various peace organizations as well as report their activities.[19]

The war with Mexico provided the first real test of the position of the Church of Christ on the question of war. The pattern of support or denunciation in the church generally followed that set by other religious groups and was determined partly by the geographic distribution of the membership and partly by the attitudes of the leadership. The most vigorous protests to the war came from the Northeast, where the pacifist sentiment was strongest. The only organized attempt by the church In this section to express its disapproval of the war came from New England, where 150 members drew up a petition voicing ardent opposition to the war. This petition denounced the action as an outright invasion of Mexico and identified the motives as a lust for additional territory and the desire to extend slavery. The petition further described the continuance of the war as "one of the greatest crimes against our modern history."[20]

That the most vehement opposition to the war should come from the North is seen by the fact that over forty per cent of the congregations of the Church of Christ were located in the East Central region, composed of the states of Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. On the other hand the attitude of members in the South was similar to that of other southerners. The states of Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, and Mississippi, contributed 16,000 volunteers for the war, approximately one in 140 for the white population. This is to be compared to one in thirty-three for the Southwest area (Arkansas, Louisiana, and Texas), and one in 2,500 for New England.[21] Some of the church's ministers rent so far as to defend the war as a struggle to free the oppressed people of Mexico from Catholic despotism.[22]

There were exceptions to the pattern on both sides, however. For example, Campbell, who lived all his life in Pennsylvania and Bethany, Virginia, now West Virginia, did not oppose the Mexican war and, in fact, did not take up the anti-war cause until after the conclusion of the conflict. On the other hand Tolbert Fanning, an influential Church of Christ minister in the Nashville and Middle Tennessee area, opposed the war vehemently. Condemning the war as “a violation of Christian ethics,” Fanning said that Christians could not participate "under any circumstances."[23]

The most pacifistic element within the church was in Middle Tennessee. The strength of this sentiment was due mainly to the influence of the many writers and ministers in the area. The most influential of these was Tolbert Fanning of Nashville, the editor of the Gospel Advocate, the most effective periodical in the church in the South. It was through the Advocate that Fanning exercised the greatest authority; however, it was Fanning who, more than any other man, trained the corps of preachers who dominated the church in Tennessee and the lower South for the next half century. It was Fanning's pacifistic pronouncements during the Mexican war that served as "a solid foundation for the later militant pacifism of church leaders in the state."[24] While virtually every major leader in the Church of Christ in Middle Tennessee followed Fanning's lead, not every lay member agreed with Fanning. In fact, many of the members of the church in this area "packed their Bibles into saddlebags and rode off to war."[25]

The same characteristics which divided the church's thinking on war were also present in the issue on slavery. As in the question of the Mexican war, the attitudes of the membership were partly determined by the position of the leaders and partly by geographic distribution, although again an irregular pattern was followed. Barton Warren Stone, for example, rejected radical abolitionism in favor of the “humanitarian emancipation and colonization" of all Negro slaves to Africa, Stone went so far as to form a colonization chapter in Georgetown, Kentucky, in 1830. Hopes for the success of gradual emancipation waned during this decade, however, and Stone eventually moved closer to the abolitionist cause.[26]

Like Stone, Alexander Campbell began his antislavery campaign on a moderate, humanitarian basis. Campbell had been a slaveholder atone time, but was converted by the anti slavery arguments of his father, and ultimately freed his slaves on a gradual basis. In 1829 Campbell, who was well respected in Virginia as an outstanding religious and educational leader, was elected as a delegate to the Virginia Constitutional Convention. Acceptance of this position brought much criticism upon Campbell, who had espoused the idea that Christians should not actively participate in governmental affairs, Campbell's critics accused him of “turning from heavenly things to follow the path of worldly ambition in politics." Campbell justified his position by explaining that he "wished to do something toward ending slavery in Virginia," and that by participating in the convention he might succeed in this effort.[27]

As the years passed, it became evident to Campbell that the moderate position on slavery was a lost cause. As the abolitionist element in the church in the North and Northeast became more restless and he was openly attacked for not coming out in favor of immediate emancipation, Campbell assumed a harder line on the entire question. Consequently in 1845 he began a series of articles in the Millennial Harbinger in which he sided with the advocates of abolition. He evaded any further pursuit of the question by reaffirming an earlier statement that American slavery was not a religious problem but a political one, therefore, a matter of opinion rather than faith.[28] He attempted to discourage any sympathy for slavery by enumerating the economic risks involved. While admitting that the Bible did not explicitly condemn slavery, Campbell felt there the real danger to be in the area of a Christian's responsibility as a steward over his possessions.[29]

Despite the moderate attitude taken by many of the better known leaders, pockets of militant abolitionism developed within the church. Nathaniel Field, a minister in Jeffersonville, Indiana, wrote in 1834 that he had determined not to fellowship as Christians with any who were slaveholders. John Boggs, abolitionist editor of a Church of Christ newspaper in Cincinnati, Ohio, remarked that a biblically-founded congregation would not tolerate slaveholders as members.[30]

Very few ministers in the church encountered Pardee Butler's experience as an antislavery preacher. Butler had been instrumental in establishing the Church of Christ in Kansas in the early 1850's as well as assembling the first convention of churches at Leavenworth, Kansas, in 1857. He first attracted attention when he began to preach abolitionism from the pulpit. As his sermons became more extreme, Butler was warned by proslavery elements in Kansas to stop his attacks. When these warnings proved unsuccessful, Butler was kidnapped by members of the proslavery faction In Atchinson, Kansas, and threatened with hanging if he did not stop. Rescued from this, Butler continued his antislavery campaign. Captured again, he was tarred and feathered and set a drift in the Mississippi river. This failed to intimidate Butler, however, and he continued to preach abolitionism. The climax came when the proslavery elements in the churches which supported Butler withdrew his funds. When he applied to the American Christian Missionary Society[31] for financial assistance, it offered to provide the aid only if Butler would "preach the gospel and keep out of politics, which in effect meant to discontinue his antislavery agitation.[32]

While there existed a distinct abolitionist group in the Church of Christ camp,[33] this faction was in the minority, for most members of the church refused to accept the uncompromising conclusions of radical abolitionism. Numerous church leaders shared the aversion of many Protestant churchmen to the extreme demands which the abolitionists espoused particularly after 1830. Such southern ministers as Tolbert Fanning and Philip S. Fall of Nashville, along with such border area ministers as Alexander Campbell, John T. Johnson, and Thomas M. Allen rejected militant abolitionism because "it smacked of a social fanaticism essentially out of step with the tolerant mind of the restoration movement. Consequently, they remained “unemotional, rationalistic moderates" and by doing so kept most of their followers in the moderate camp.[34]

The church's aversion to "preaching politics” determined the position of many of its leaders on the subject of slavery. One of the primary tenets of the restoration movement was that church and state should be distinctly separated. For the Church of Christ the restoration movement was essentially a religious one with matters of faith assuming primary importance over all temporal affairs; hence political questions were relegated to the realm of opinion. This helps to explain why the Church of Christ never openly split over the issues which divided other religious groups and resulted in the Civil War.[35]

The comparative unity which existed among the congregations of the Church of Christ in Middle Tennessee on the issue of slavery is attributed to a number of factors, he of the most important of these was the relative freedom of much of the Middle Tennessee economy from slave labor.[36] Connected with this is the fact that the appeals of the church found response among the poorer farming element of the area. Of no small consequence was the attitude of the Gospel Advocate, the most powerful periodical in the church in the South. Edited by Tolbert Fanning, the Advocate officially assumed a neutral position on the question. Unofficially, Fanning leaned somewhat toward the proslavery camp. He took the liberty to write in the Advocate that he implicitly accepted the enslavement of the Negro. Fanning stated the three conditions upon which he could accept this state of affairs: first, men may be deprived of liberty because they may not be qualified to enjoy it; secondly, slavery is permissible if it serves the good of those in slavery; and thirdly, the regard of those whose qualities fit them to rule over others must be preserved. Fanning was quick to point out, however, that this was only a personal conclusion and that he could not speak for others on the matter. He expressed the belief that all social ills could best be alleviated through individual action.[37]

In summation, then, the position of the Church of Christ on the questions of war and slavery hinged primarily upon two factors: the geographic distribution of the membership and the positions of the leadership. Members in the North, especially those In New England, were pacifist icon the topic of war while their counterparts in the South, although deploring war as an evil, were not entirely averse to the idea of participating in war on a moral and sectional basis.

On the question of slavery the most ardent abolitionists in the church were those in New England. These tended to look upon slavery as a moral wrong that could be neither justified nor tolerated; therefore, it had to be abolished at all costs. Members of the church in the South, while regretting the trepidations brought about by the moral implications of slavery, nevertheless justified its existence. Members in Middle Tennessee viewed the question as one of a political nature to be settled on an individual basis by one's conscience. By dismissing the issue in this manner, they succeeded, in evading any real confrontation which could have divided the church.

The third issue facing the Church of Christ in the first half of the nineteenth century was one which confronted the entire country: education. The trends which characterized American education in this period were present in the educational efforts of the church. The church school founded in the nineteenth century was usually designed to meet the needs of the community in which it was located. It was established either by an individual or a small group of people affiliated with one of the major religious groups, With few exceptions the school was beset with numerous problems which prevented any real progress in providing an adequate education for the public. The first and often most critical issue which the school had to meet was that of financial support.

Churches were expected to supply students, furnish publicity for the school, and give the school the opportunity to make its appeal before the congregation "with some degree of sympathy on sectarian grounds.[38] Lay members of the region in which a college was located were expected to give as much as possible toward the maintenance of the institution; however, donations of money were few and such gifts as were made usually consisted of labor, agricultural produce, lands, or a combination of these.

Because of the existence of an unsure source of capital, a college had to struggle over a period of years before it was either firmly established or suffered its demise because of the lack of support. In many cases the colleges which became established did so only because they begged for aid "until even their friends sickened at the sight of a subscription list and the sounds of old arguments."[39]

When the founding of an educational institution was not under the auspices of a religious denomination the problems were more acute. The question of location in such instances was of prime importance. Competition among the communities was at times so keen that the entire affair often resembled an auction with the highest bidder receiving the prize.[40] If the location of a college was settled in this manner, the community which was awarded the college often found itself unable to support the institution, having exhausted its resources securing the contract. In such instances the college often found it less difficult and often necessary to close its doors permanently rather than attempt to move to a different location. A number of private and church related colleges met their fate in this way.[41]

Another problem common to many of the early colleges was internal dissension, which took on a number of forms. One of these was discipline, perhaps the most common question facing the schools. The student body often consisted of youth accustomed to the undisciplined and often capricious conditions of the isolated communities and the rigid conditions of the classroom often resulted in open conflicts with the faculty. Dissension also existed between the faculty and the trustees who exercised considerable authority in planning the policies of the school.[42]

Natural disasters proved to be a major problem to the isolated or frontier college. The most common and certainly the most destructive of these calamities was fire. Many of the schools which had no permanent endowment with which to provide funds for rebuilding following such a misfortune were forced to close. A second calamity was disease. Although great care was taken to choose locations most conducive to the health of the students, the prevalence of diseases such as malaria, smallpox, cholera, and various fevers at times led to the suspension of school for prolonged periods. This problem was uppermost in the minds of the administrators and trustees as they attempted to persuade students to attend their colleges. One of the most common advertisements of the school catalogues of the nineteenth century boasted the fact that the school was located in the best and most healthful environment, "entirely removed from all malarial influences.[43]

Many of the colleges founded in the South during the first half of the nineteenth century were the products of religious effort. Church leaders propagated the idea that education was the function of religion by predicting that profitable results would benefit society if education and religion were united and that fearful consequences would follow if they were not. Between 1820 and 1860 over fifty church colleges were established in the South. The primary purpose of this outburst of educational effort was to fulfill the critical shortage of educated ministers. A secondary purpose was to perpetuate the basic teachings of the church.[44]

Private and denominationally controlled academies[45] remained popular in the South longer than elsewhere primarily because the public high school which replaced the academy was late in coming to the South. These academies fell into two classifications, the first of which was merely an expansion of the tutorial system which was common to the South. This type was highly localized and remained under the control of the individual or group which had initiated the tutorial system. The other class consisted of larger more organized efforts which were generally chartered by the state. This type had a wider patronage because of the excellence of the work offered.[46]

The purposes of the private academies were "to develop the moral and spiritual natures, give emphasis to the cultural side of education, and develop a body of intelligent citizens.[47] Although generally religious in tone, most the academies managed to avoid the narrow sectarianism which otherwise divided the people of the South religiously and politically. It should be pointed out, however, that this non-doctrinaire attitude was necessary in order to win the allegiance and financial support of the community.

Control of these schools remained in the hands of the founders or other private individuals who were mentioned in the charter as a "body politic” or "board of trustees" empowered to set up the necessary administrative machinery. The board or governing body also exercised considerable influence over the president and faculty in determining the school policy. Although classified as "private” schools, these academies in effect were semipublic institutions, for they relied upon the public including individuals of other denominations for their support.[48]

The Church of Christ assumed a more liberal attitude towards education than it did upon the questions of war and slavery. In fact, education was viewed as a cardinal tenet in the development of the religious, social, and moral fiber of the nation as well as the members of the church.[49] The acceptance of the responsibility to educate its members was stressed as one of the three chief functions of the church.[50]

The first college established by the Church of Christ in the South was Bacon College, founded in 1836 at Georgetown, Kentucky,[51] Walter Scott, one of the outstanding leaders of the restoration movement in Kentucky, as one of its first presidents. While a number of other colleges were founded in the first half of the nineteenth century, none exceeded Bethany College in prestige and influence. Founded by Alexander Campbell in 1840 in Bethany, Virginia, now West Virginia, the school was primarily a "preacher's school," although it attempted to cater to the needs of every student.[52]

Franklin College, founded in 1845, was the first Church of Christ college in Tennessee. Located some five miles east of Nashville, the school, a product of Tolbert Fanning, reflected the conservative ideas of Fanning and other leaders of the church in the area.[53] Although it was in existence for less than a quarter of a century, Franklin College exercised considerable influence upon members of the Church of Christ in Middle Tennessee. One of the primary reasons for the school’s failure was Fanning's refusal to acceptor seek monetary endowment.

In this matter Fanning encountered the opposition of Campbell, who recognized the necessity of providing some sort of permanent support. Said Campbell, "Not a College in the world has existed one century without endowment, nor can they. This fact is worth a thousand lectures. Can any one name a College that has seen one century without other funds than the fees or tuition?"[54] Despite Campbell's warnings against the failure to provide such an endowment, schools supported by the Church of Christ continued to spring up without this benefit.[55]

Franklin College was unique among early church of Christ schools because it was opened as a manual labor school.[56] One of Fanning's purposes in operating the school was to bring education within the reach of the poor. Perhaps this explains the silence of Franklin's charter on the subject of religion. Although Fanning proposed to use the Bible as a textbook in the school, he did not intend that the college be denominational in any way, or for it to be a "preacher's school.” In addition, the school had no requirement that the board and faculty be members of the Church of Christ, although most were.[57]

An important adjunct of the educational efforts of the church was coeducation. Campbell was among the first to voice his approval of this undertaking. In 1838 he wrote:

The education of the female sex, I contend, is at l east of equal importance to society as the education of our own. In moral results it is perhaps greater. Their influence in extending and perpetuating general education, as well as their moral influence, is likely to be greater than ours.[58]

Coeducation in the church's schools was concentrated primarily in the North because higher education for women in the South came from schools designed especially for them.[59] Consequently coeducation in institutions of higher learning was unknown in Tennessee during the first half of the nineteenth century. Burritt College was the first school in the state and the South to admit girls on an equal basis with boys.[60]

The founders of Burritt College chose the name of Elihu Burritt to affix to their school because they admired the initiative, perseverance, and determination which characterized Burritt's rise to national prominence.[61] While there was not an overwhelming amount of pacifistic sentiment within the Church of Christ, there was nevertheless a sufficient amount for the small band of Christians in the isolated village of Spencer, Tennessee, to know of the life and work of one of the outstanding leaders in the peace movement. Generally the Church of Christ followed the pattern set by other religious groups in questions such as war and slavery. Geographic distribution of the membership and the stands taken by the leadership determined the thinking of the laity; however, deviation from this pattern was exhibited.

Burritt College epitomized the attitudes taken by the Church of Christ on the matter of education and also reflected the traditional developments in the educational field during the first half of the nineteenth century. Problems of discipline, administration, finance, and maintenance which plagued the frontier college combined to shape the destiny of Burritt College as the "pioneer of the Cumberlands."

CHAPTER II

BURRITT COLLEGE TO THE CIVIL WAR

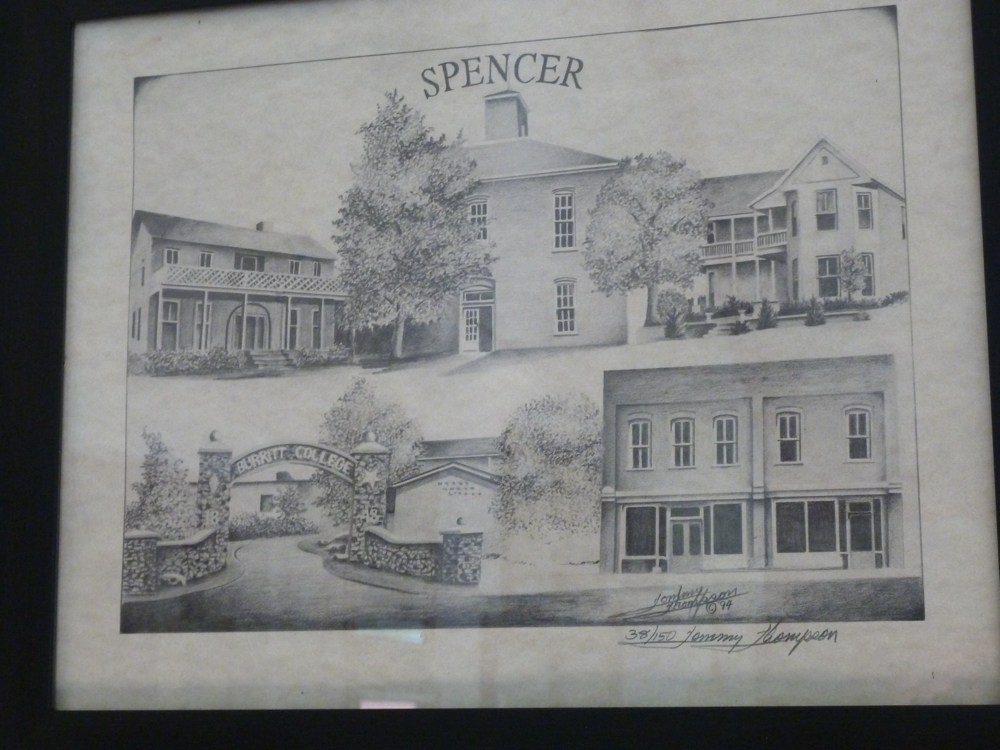

The story of Burritt College is the story of Van Buren County, for whatever prestige the area has received has been the result of Burritt’s presence. The town of Spencer[62] owes its existence to Burritt College, for many parents who enrolled their children in the school moved to Spencer to eliminate many of the costs of education. The conditions and circumstances surrounding the establishment of Burritt College are closely connected with the history of Van Buren County.

The people who settled the Cumberland Plateau in the latter half of the eighteenth century came mainly from North Carolina and Virginia. They were of basic Scotch-Irish stock with strongly Calvinistic concepts, Among the prominent family names who settled the area in the nineteenth century were Clark, Walling, Glllentine, Stewart, Parker, Smith, Seitz, Trogden, and York.[63]

In 1839 state senator Samuel Hervey Laughlin of McMlnnville[64] received a petition from Uriah York, William Armstrong, and others, containing the names of "three or four hundred citizens” of the Caney Fork, Rocky River, and Cane Creek areas of Warren County requesting the establishment of a new county. Laughlin succeeded in getting the legislature to authorize the new county, which he named Van Buren, after the eighth president of the United States.[65] The town of Spencer was settled shortly thereafter and was named by Samuel Turney, state senator from White County.[66] A.K. Parker, a native Virginian who owned some 5,000 acres of land in the vicinity of Van Buren County, deeded fifty acres of land for the town site and built the first house there. John Gillentine, also a Virginian, followed Parker into the area and along with John Stewart built a storehouse and a small log structure which served as the first courthouse.[67] The first court was held on April 6, 1840.[68]

Spencer was isolated from the main arteries of transportation of the area. The nearest towns were McMinnville, eighteen miles west, and Sparta, fifteen miles north. Roads leading to and from Spencer were extremely rough, and a journey to either of these towns usually required several hours, particularly on the return trip up the mountain. The Nashville, Chattanooga, and St. Louis railroad, the only other means of transportation serving the area, was not begun until 1848 and was not completed until 1853. The nearest branch of this line was located at Doyle Station, nine miles north of Spencer, in White County.[69]

Initial census reports for Van Buren County, conducted in 1850, indicate the county had a population of 2,674,[70] while Spencer's population stood at 164. [71]It was the latter group which made the decision to establish a college in Spencer, although support for the undertaking was promised by the people In the county as well as citizens living in the surrounding counties. This support was given despite the number of educational efforts already underway. However, the group responsible for the establishment of Burritt College felt the need to found a school of higher caliber than that of existing institutions.[72] In addition, the isolation of the community, compounded by poor transportation, plus the inability of the people of the county to send their children to better schools in McMinnville or other towns[73] prompted the people of Spencer to go ahead with plans for the college.

Of no small consequence was the fact that most of the colleges of the area were associated with religious bodies other than the Church of Christ.[74] Arguments among members of this group expressing the desire for a college resembled that later advanced by J.A. Hill, a future secretary of Burritt's board of trustees. In arguing that the school have a religious emphasis, Hill stated:

As a people of the South and Southwest we are not very far behind the foremost, in numerical strength, and material Resources, yet what have we done in preparing for the education of the rising generation, nay, even our own children?

While the Methodists have a magnificent university at Nashville, the Baptists one at Jackson, the Presbyterians one at Clarksville, the Cumberlands one at Lebanon, the Episcopalians one at Sewanee, what have we? Where have we a first-class college in the South built by our money, and controlled by us as a people, to which we may send our children, where our morals will be safe, and their education thorough?[75]

In short, then, Nathan F. Trogden’s earlier suggestion of April, 1848, that a college be established in Spencer was readily accepted by the townspeople, because the conditions made such a suggestion feasible and attractive.

The charter granted to the stockholders made them “a body politic and corporate by the name of Burritt College, and shall under that name have succession for five hundred years.” Each stockholder was given one vote for each share of stock he held. This arrangement made it possible for the school to be dominated by one man or a syndicate representing the policies or interests of one man, and it resulted in a number of conflicts between the president of the college and the stockholders. From the stockholders a board of twelve trustees was to be chosen, with the president to be an ex officio member. These trustees, whose terms ran for two years, had the power to elect the president, hire "such professors, tutors and other officers. . .as they may deem necessary," and make "such by-laws, rules, and regulations as in their opinion may be expedient or necessary,"[76] Also delegated to them was the authority to subscribe stock in the college, contract the building of additional structures on the campus, and advise the president on the policy of the school.[77]

Upon completion of the main structure, the school opened on February 26, 1849, with seventy-three students and three teachers.[78] The total amount of money available to the college that year from all sources, primarily tuition and donations, amounted to $1,500.[79] Isaac Newton Jones, a native of McMinn County, Tennessee, and one of the chief promoters of the college, was the first president. Although he was well liked by the trustees, Jones lacked the academic training needed for the position.[80] Consequently the school failed to make the progress the trustees desired. Jones succeeded, however, in establishing the type of curriculum which Burritt was to follow for sixty years virtually without change. The basic courses comprising the curriculum were classical and included Latin, Greek, philosophy, mathematics, logic, natural philosophy, and evidences of Christianity.[81]

After serving one year Jones resigned, He and W.B. Huddleston, a member of the board of trustees, secured the services of William Davis Carnes to succeed Jones as president.[82] Expanding upon the start made by Jones, Carnes made Burritt the well-respected institution it was, for he shaped its policies and set its standards. That the trustees were pleased with his administration is seen by the fact that Carnes, with the exceptions of William Newton Billingsley and Henry Eugene Scott, served as president of Burritt longer than any other man.[83]

Carnes was born in Lancaster district, South Carolina, in 1805, but moved with his parents to McMinnville, Tennessee, when he was five. His childhood was spent in Warren and Rutherford counties. After marrying at an early age, he moved to the Sequatchie valley, where he became a successful farmer as well as a preacher for the Church of Christ. Without formal education, Carnes determined to secure his formal training and was persuaded by a professor James Garvin of East Tennessee College to enroll in that school. After selling his farm in Pikeville, Carnes moved his family of seven to Knoxville in 1839, at which time he entered the school. He was then thirty-four years of age.[84]

Carnes finished the school's four year course in three years and went on to receive the master's degree from the same institution. Upon completion of this degree Carnes was made principal of the preparation department. After two years in this capacity he became a professor of English language and literature.[85] A serious illness forced Carnes to abandon his teaching duties at East Tennessee College, and he returned to Pikeville, where he farmed and taught locally until the presidency of Burritt was offered to him. Carnes accepted the position when he learned that he would be given a free hand to initiate whatever reforms he deemed desirable and that the trustees, especially Jones and Huddleston, were members of the Church of Christ.[86]

Upon becoming president in 1850 Carnes initiated several reforms in the school's operational make-up. During his first year Carnes introduced coeducation at Burritt, a step taken despite much opposition on the part of many supporters and citizens in Spencer. It was this step which had the most far-reaching effect in Burritt's history, for it singled the school out as the pioneer in bringing coeducation to the South. Many of the school's supporters looked upon this move as a dangerous experiment at best. Few parents regarded their daughters safe at a boarding school where they would be associated with the boys almost as intimately as sisters with brothers in the family circle."[87] To offset this opposition Carnes erected a small dormitory adjacent to his house and appointed his daughter Mary the head of the female department.[88] While there was some dissent among Burritt officials over the acceptance of girls at the school, most defended Carnes' action by emphasizing that it was,

. . .God's law that the young of the opposite sexes should exert a healthful influence in the formation of each other's characters, and no place is better fitted to this purpose than the class room and lecture room. By being continually associated at the table and in the class room, the young man does not lose his gentleness nor the young lady her strength. . . . Parents having boys and girls to educate can place them all at the same institution, where brothers and sisters can enjoy each other's society.[89]

Despite this support, however, the pressures and opposition of members of the Church of Christ in the area forced Burritt officials to include in the school's regulations a rule governing the male-female relationship on campus.[90] This rule forbade all oral and written communication between the students except that permitted by the faculty. This rule did not apply to brothers and sisters, however, so long as they did not abuse the privilege by seeing and speaking to others at the time of visiting each other.[91] Failure to comply with this rule resulted in suspension of both boys and girls for a lengthy period.[92] The rule was lifted only for special occasions such as athletic events or school picnics to nearby Falls Creek Falls on weekends. These chaperoned dates were the only ones permitted by school Officials.[93]

In keeping with the general purpose of the school to develop the complete student, the social relation of the sexes was made "an object of sleepless vigilance." All social meetings including the weekly debates of the literary societies[94] were arranged by the president. The daily chapel exercises followed rigid patterns with boys and girls marching into the auditorium separately and being seated on separate sides of the auditorium with a rope between them designating a partition.[95] It was because of such close supervision that coeducation was maintained and later won the approval of even the most severe critics. Carnes continued the classical curriculum which Jones had introduced the first year; however, he modified it somewhat to conform to that of East Tennessee University.[96] Among the modifications was the inclusion of a number of elective courses not included in the first year's curriculum. These included French, German, drawing and painting, instrumental music, and needlework and embroidery.[97]

Each student was required to take at least three but not more than four courses in any term unless approval was granted by the faculty. While all students were enrolled either in the "regular course or the "English department," the college was divided into two levels, each with its own course of study, The first of these, the academical department,[98] was subdivided into two classes, with the first, or lower class, required to take Latin, mathematics, geography, orthography (spelling), and writing the fall term, while the only change for the spring session was the deletion of orthography and the addition of history. Greek and English composition were the only additions to the second class.[99]

In the collegiate department Latin, Greek, and mathematics were required of freshmen, sophomores, and juniors. Freshmen also were offered physiology, sophomores had rhetoric and logic, juniors found surveying, philosophy, political philosophy, and botany a part of their course of study. The only major changes in requirements occurred in the senior curriculum, Latin was deleted altogether and mathematics was required only for the fall session. In place of these chemistry and mental philosophy were offered the first term, along with geology and political philosophy. The spring session included astronomy, moral philosophy, theology, criticism, and a general review of Latin and Greek.[100]

Chapel attendance was made an integral part of the daily exercises by Carnes and was required of every student. In addition, Carnes required a half hour of calisthenics each day; however, the gymnastics program was not made a permanent part of the curriculum until 1879.[101]

The collegiate year was divided into two terms of twenty-one weeks each, and were classified "fall" and “spring” terms. The fall session began the last Wednesday in July, and the spring term started the last Monday in February.[102] The courses offered in each of the departments were one-term courses. This permitted students to attend school in "broken terms.” Many took advantage of this arrangement to attend the fall session and work the spring term, Inasmuch as most of the boys had to assist in farm work in which most of their parents were engaged. Consequently the educational career of many students extended over a number of years.[103] Each of the terms amounted to one academic year. This arrangement made it possible for Burritt students to complete two academic years in two terms and also explains why many students finished at an early age.[104]

Burritt College offered the Bachelor of Arts degree during the early years and by 1871 was offering its equivalent to the female.[105] The Master of Arts degree was conferred upon those who had "attained to fair scholarship, and to eminence in some literary or professional calling."[106]

Entrance requirements for the school were liberal. The only condition which prospective students had to meet was to "present satisfactory evidence of good moral character; to read (or have read) the laws of the institution; and to pay the required contingent fees cash in advance."[107] Expenses were charged by the term and remained fairly constant throughout Burritt’s history.[108] Maintenance fees and tuition charges ran as follows:

Tuition in the primary department, per session

... $10.00

Tuition in the advanced branches, per

session....... 15.00

Boarding and washing, per

session........................ 30.75

Contingent Fee per session ………………...……. 1.00

Tuition On The Piano, (extra) ……………………

18.00

Use of the instrument, (extra) …………….……..

2.00

Tuition On The Guitar, (extra) ……………………..

18.00

Tuition on the

flute.................................................... 15.00

Tuition on the violin ……………………….............

15.00

Tuition in painting and drawing

portraits................ 10.00

Tuition in French

…………………………................ 5.00

Tuition in Drawing, (extra) …………….………....

35.00

Students entering within two weeks of the school's opening were charged full tuition; those entering after that time were to pay from the time of entrance. The only exception to this rule was in cases of protracted sickness which amounted to at least two weeks atone time. Students who were expelled forfeited the entire amount.[110]

Carnes’ first year as president proved so successful that Burritt outgrew its facilities.[111] He urged the trustees to issue a new stock subscription to build additional dormitories, but when his request was turned down he sold his farm in Pikeville and gave the money toward the erection of the needed buildings. The result was three small brick edifices which served as dormitories for boys. In return for his action the trustees awarded Carnes stock in the college at par value equal to the amount he invested in the structures. These shares in addition to those he already owned gave Carnes a controlling interest in the college.[112]

During his first year Carnes introduced the practice of Bible reading as an integral part of the students' activities on campus. Although Carnes' real interest was in secular education and the establishment of academic quality, it was through his influence that the school's atmosphere became congenial to religious interests.[113] To help facilitate the study of the Bible by students, Carnes required them to attend Wednesday evening Bible classes and Sunday School. Both of these were conducted in the school auditorium. Sunday morning services were held in the church building.[114] It has been said that this high moral and religious tone was one of the primary reasons for Burritt’s growth.[115]

Considered a pioneer among the Churches of Christ in the South in combining a career of teaching and preaching[116] Carnes established himself as a strong disciplinarian. He viewed one of Burritt's highest functions to be the building of Christian character. To accomplish this, he "strove religiously to lay the foundation. . .of virtue, honesty, and perseverance.” While attempting to establish high scholarship and efficiency at the school, he also sought to make Burritt "the School of the Heart.”[117]

Burritt's supporters were in full agreement with this principle. In their view, it was not necessary that the institution have two hundred, one hundred and fifty, or even one hundred students; but it is necessary that it should have a class of high-minded, noble, Christian young men and young ladies. For the education of such we devote our time and means, and have none of these to give to those who do not intend to make such characters.[118]

Because of Carnes' strictness and the strong skepticism of some supporters of the school among members of the Church of Christ that coeducation would succeed, every attempt was made to control the students activities on campus.[119] Despite these efforts, however, a number of problems with discipline developed, The greatest of all was whiskey as the hills surrounding Spencer abounded in “moonshine" operations. Disregarding the warnings of the school regulations and those issued periodically by the faculty, a number of young men brought whiskey onto the campus. Attempts by the faculty to curb its use were thwarted by the fact that the owner of one of the stills from which the students received their supply was a preacher "of great influence.[120]

In order to help combat the threat which whiskey presented, the faculty was given additional powers to govern more closely the activities of the boarding students. It was part of their duty to

know how, when, and where the young man spends all his time. It is fully realized that when a large number of young men are associated together at college, without parental advice or restraint, some of them will go to ruin unless the teachers take the place of the parents, and, by wholesome restraint, control their inclinations and desires and, by salutary advice, direct their young footsteps into the way of virtue.[121]When this step failed to solve the problem, Carnes submitted to the trustees a resolution which imposed severe academic restrictions and penalties upon students who were in any way associated with the liquor traffic. The trustees granted approval to these limitations, and as a result a number of students were expelled from school. There were occasions in which twelve or more students many of whom were “scions of prominent families” were expelled at one time.[122]

This fact did not prevent Carnes from executing the rules of the college in an impartial fashion, however, The upshot of this policy was to provoke the resentment of a number of his supporters in Spencer, Tennessee, many of whom broke with him openly calling him "a tyrant and a fanatic."[123]

When the whiskey problem persisted, Carnes proceeded with the assistance of state representative, John Myers of Pikeville,[124] to draw up a proposal forbidding the sale of intoxicants "within four miles of a chartered institution of learning except in incorporated towns and cities," and went to Nashville to secure such a law.[125]

Shortly after Carnes returned from Nashville his home in Spencer mysteriously burned. While he had no proof as to the cause of the fire, Carnes believed it to be the work of persons who opposed his efforts to eliminate the whiskey threat at Burritt.[126] Carnes was so embittered by this act that he sold his stock to the other stockholders, resigned as president, and moved to Knoxville, where he assumed the presidency of East Tennessee University.[127] Carnes was a vital asset to Burritt, for he stabilized it and provided the forceful administration needed to assure its future growth.[128]

Carnes was succeeded as president by John Powell, who, like Carnes, was both a minister and educator. Powell, a native of McMinnville, had served as president of Central Female Institute there before coming to Burritt.[129] Little is known of Powell except that as president of Central Female Institute he was described as "an efficient tutor and a man of fine accomplishment and sterling worth.”[130]

Powell's first term[131] proved to be uneventful. The political developments which culminated in the Civil War prevented Powell and school officials from doing little more "than hold the school together.”[132] The school closed completely in 1861 following the conclusion of the spring session.[133] One of the more immediate reasons for the closing was that many of the boys volunteered in the Confederate army.[134] A more significant reason was that Powell could not prevent a schism from developing between the trustees and himself.[135]

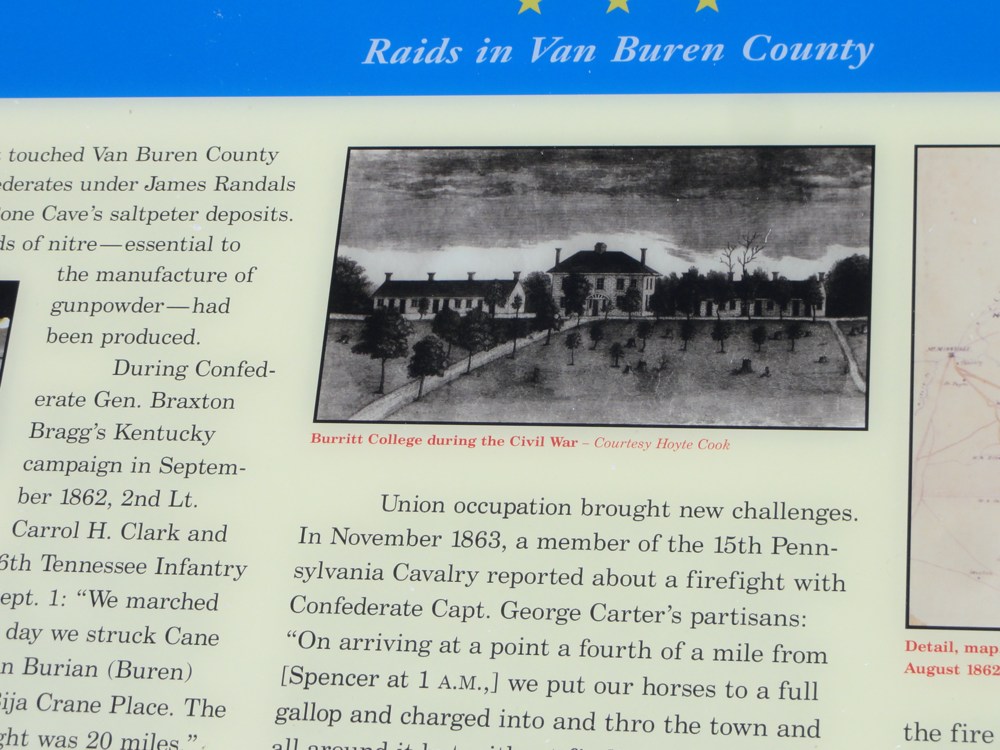

With the suspension of school in 1861 and the enlistment of many of Burritt's male students, Spencer became more isolated and deserted; however, this isolation helped the town to escape the ravages of the armies as they maneuvered through Middle Tennessee. The nearest military posts were located at McMinnville and Sparta, but the roads leading to Spencer proved so unsatisfactory that even the foraging parties of the armies made no attempts to penetrate in to the valleys surrounding the town until the Federal troops occupied the area during the closing months of the war.

Like their southern counterparts in the Mexican war, many members of the Church of Christ in Spencer "packed their Bibles into their saddlebags and rode off to war.” The majority of the people in Spencer and Van Buren County were sympathetic with the southern cause and continued to support it throughout the war, although this support was rather inactive during Federal occupation of the area.[136]

Volunteers from Burritt College and Van Buren county composed one of ten companies from seven Middle Tennessee counties which fought under Colonel John Savage of McMinnville, commander of the Sixteenth Regiment, Tennessee Volunteers.[137] Company I, composed of men from Van Buren county, consisted of 121 men and officers. The fourth ranking officer of the company was Third Lieutenant A.T. Seitz,[138] who graduated from Burritt in 1854 and who became its sixth president.[139]

Also included in the ranks of Carroll Henderson Clark, later an ardent supporter and trustee of Burritt College. Although he was not educated at Burritt, Clark did receive what schooling he had at Spencer, where he had moved with his parents in 1846 at the age of four, He received his earliest education in an old schoolhouse which was minus a floor and chimney. For a time he studied under a Reverend Patrick Moore. Later he attended York Academy in Spencer.[140] It was while he was a student here that the Civil War broke out, and he left to enlist in the Confederate army as a private.[141]

During the winter of 1863 Carnes moved his family from Nashville to Spencer because the mountain town "was comparatively free from restraints” brought on by the war.[142] Upon finding out that Carnes had moved back to Spencer, the town's citizens made numerous requests upon him to open a "war school" on Burritt's campus. While willing to do so, Carnes expressed the fear that either Federal troops in the area or bands of Confederate guerrillas in the mountains would prevent such an undertaking. Carnes' reluctance was prompted by the knowledge that the leader of the guerrillas was the owner of a tavern in Spencer when he had attempted to secure a prohibition law in 1856 forbidding the sale of liquor near Burritt.[143]

Despite the objections, however, Carnes was persuaded by his friends to attempt the establishment of a school at Burritt. With the assistance of Judge Thomas N. Frazier[144] Carnes persuaded the commander of the Federal troops in the area[145] to issue a special order granting immunity and protection to the property of Burritt College.

The school opened in January of 1864 and stayed in operation for two sessions.[146] The second session was marred by reports that the Confederate General, Joseph Wheeler, was to make a raid through Middle Tennessee in an effort to drive the Federal troops from the area. Southern sympathizers in Spencer met this news with joy, giving Federal troops in the area much concern, who complained that Spencer was "a nest of Rebels who made the school a pretext for gathering there to give aid and comfort to the guerrillas.” A detachment of Federal troops closed the school and sent the students and temporary residents home.[147]

Following the breakup of the school, Federal soldiers occupied the school grounds. The buildings were used as barracks for the soldiers while the dormitories served as stables for the horses. By the conclusion of the war the campus was laid waste; the buildings partially destroyed and the student body scattered.[148] Thus the efforts to reopen Burritt in 1866 were made more difficult than they would have been had the school grounds remained intact. However, the spirit of the school's supporters, as symbolized by the name and seal of the school,[149] triumphed in the end and allowed Burritt College to become one of the most influential schools in Middle Tennessee following the Civil War.[150]

Thus the Civil War that closed Burritt's doors temporarily also closed the first chapter of its history. This chapter was a successful one, for despite the problems of administration, discipline, financing, and isolation, Burritt’s leaders succeeded in establishing "a school of the heart," one which became a fortress of knowledge for the folk of the Cumberland Plateau.

The characteristics which typified the school throughout its history were due mainly to the work and influence of President Carnes. The school's reputation as a stronghold of discipline, moral strength, and Christian principles permeated the entire area for the next seventy-five years.

CHAPTER III

THE UNSTABLE YEARS: 1865-1890

The year 1865 brought peace to the South; however, little else remained the same as it was prior to the war. The economy was changed and the lives of the people made more adverse by the accompanying political and social difficulties. While they escaped the harsher indignities of the postwar depression, residents of Spencer, nevertheless, felt the repercussions of having lost the war. The town already isolated by its geographic and economic conditions became even more separated from the surrounding area. In fact, Spencer experienced a loss in population because of the acute economic conditions, declining from just over 400 to 283.[151]

Despite the setbacks brought on by the war and the ensuing depression, the friends and supporters of Burritt determined to reopen the school. In 1866 the trustees sold part of the college grounds to raise funds to repair the damaged buildings. Not having an endowment,[152] the college had no available funds from which to draw teacher’s salaries or operating expenses. Consequently the trustees continued the policy first enunciated in the charter which stipulated that teachers accept shares of stock in the college as payment of salary. With this condition the meager faculty[153] returned to the school in January of 1867. At that time the college was reopened.

Martin White was chosen as the first postwar president. White, a native of Virginia, had walked from North Carolina to Spencer as a young man to enter Burritt.[154] White remained at his alma mater for three years and devoted himself to trying to rebuild the school to its former stature. These efforts were compounded by the difficulty in raising funds. As a result the growth of Burritt was negligible during his term. Only two students were graduated during the first two years; however, by 1869 most of the former students had returned, and this resulted in an increased graduating class in 1869 and 1870.[155]

Because of ill health White resigned in 1870 and was succeeded by a former Burritt president, John Powell,[156] whose second term, like the first, was without any significant events. At the close of the 1872 session Powell had sold his stock to one of the trustees Elijah Denton, who was given the responsibility of finding a successor to Powell. Denton, a close friend of William Davis Carnes, persuaded Carnes to return to the school and assume the presidency.[157] Carnes was at this time the president of Manchester College, another school supported by the Church of Christ. He resigned his position in the spring of 1873 end returned to Burritt.[158] At the time of his resignation from the Manchester school he had been president of that institution for seven years.[159]

With a seemingly natural bent for challenges, Carnes set about to make Burritt the prestigious school it was before the Civil War. Because of his advanced age, however, Carnes did not experience the success which characterized his first term.[160] In addition, the concern for morality and discipline assumed first place in Carnes' priorities for the school at a time when the harder realities of finance and aggressive leadership were more needed. Consequently progress at the Cumberland mountain school was delayed by many years until new blood was introduced into to the leadership.

In keeping with his concern for the moral development and strong discipline of the students, Carnes first enunciated the daily routine governing the students' activities. The school day began at five in the morning and extended until nine o'clock in the evening. The students spent the first half hour of each day arranging their rooms for inspection.[161] Following this, one hour was devoted to study and class preparation before breakfast. After the morning meal the students marched in to the auditorium for a thirty minute devotional period, which consisted of singing, prayer, and on occasions a talk by the president or a prominent visiting preacher.[162] At eight-thirty the students practiced vocal music. Class recitations followed until twelve o'clock when one and one-half hours was given to lunch. Recitations then continued for the remainder of the afternoon.[163]

At the conclusion of the class day another devotional period was conducted, which, like the one in the morning, each student was required to attend. The evening meal concluded the day's activities. Following the meal the students were required to spend two hours in private study in their rooms. At nine o'clock a bell ending the day was rung. Each student has to be in bed and have his light out when the bell rang, or stern disciplinary action was taken.[164] To insure that all students adhered to the rules, the faculty reserved the right to make room checks "to see if the occupants are engaged in legitimate pursuits.[165] A later president explained that this rigid schedule was necessary "in order for the student to accomplish the most work, and we have observed that the youth require close attention in order to get them to direct their efforts in the right direction."[166]

Remembering his experiences with the whiskey problem, Carnes redoubled his efforts to control the students' activities on campus. The results of these attempts were so effective that a half century later the school was still following the principles first enunciated by Carnes. As late as 1914 the purpose of the discipline at the school was "to save young men from their evil propensities and appetites and to make them honorable, noble, and useful citizens." It was much better for the young men to be uneducated than be "bankrupt in morals." Declaring that hundreds of young men had been ruined in the colleges because they were turned loose in "large cities, full of vice, wickedness, and dissipation, with none but the wicked to guide their footsteps," Burritt determined to avoid such effects by exercising at all times "the closest scrutiny" over the young men committed to its care. When, in the eyes of the school, a young man displayed a will which could not be controlled, he was sent home.[167]

All behavior "calculated to corrupt the morals of youth” was prohibited. Swearing, the use of obscene language, gambling, card playing, smoking, and drinking were forbidden.[168] Later the school limited the number of visits to the parents and other relatives who lived out of town that a student could make. “Such visits,” it was believed, "cause students to lose a good portion of time, and often loss of lessons of importance, and imperfectly learn others essential to their progress.” It was also believed that visiting "begets restlessness in the whole class, until many want to visit home and friends when it is impossible for them to do so.[169]

Student life, then, was somewhat austere and simple, but was an a high intellectual and religious plane. Because of the close supervision and limitations of the students, extracurricular activities took on greater importance in campus life. Such activities centered primarily around the weekly debates conducted between the two literary societies formed by the students. The first of these, the Philomathesian Society, was founded in 1851 by twenty-four male students "for the purpose of mutual improvement in the arts and sciences," to interest students "in the world's truly great literature," and to cultivate the students' social characteristics.[170]

The Philomathesians debated questions of literary, religious, and social merit; however, the bulk of the debates consisted of rhetorical and classical subjects, inasmuch as the constitution forbade the discussion of any question "either political or immoral or bordering on immorality or sectarian," Despite the restriction, however, questions of a political nature proved to be one of the favorite topics of the society. Among the topics which brought lively discussion from the members were: "That Napoleon’s banishment to St. Helena was justifiable;" "That Robert E. Lee was a better general than Grant;” “That the Southern States had a constitutional right to secede from the Union;" and "The Merits of Socrates as a philosopher.”[171]

All male students were eligible for membership into the Philomathesian Society, The membership fee was fifty cents, and monthly dues amounted to ten cents per member.[172] A two-thirds vote of the membership was necessary to ratify a new member. Initiation consisted of a simple oath of allegiance by the prospective member "to promote the welfare of the society."[173]

Failure to adhere to the rules of the society resulted in fines and exclusion from meetings. Fines were levied against members for passing between the president and the speaker, speaking without first rising to the feet, speaking without first addressing the president, resting feet upon society property, leaving the room without permission, impersonating the president, and spitting upon the walls, carpet, and furniture. In such instances the guilty party was fined not less than ten cents nor more than twenty-five cents for each misdemeanor.[174]

The second of the literary societies was the Calliopean Society, founded in 1878.[175] The charter members consisted of thirteen members of the Philomathesian Society. Conducted similarly to the Philomathesian Society, the Calliopean Society was at first open only to boys; however, after the Philomathesians accepted girls into membership In 1885, the Calliopeans followed suit in 1887.[176] This action "became a healthful factor in the social, as well as the intellectual, development of these organizations.”[177]

The school set Saturday aside as the day on which the two societies conducted their discussions. At first the boys refused to let the female members participate in these discussions with them; instead the girls were given one Saturday each month to themselves, whereas the male members reserved the other three Saturdays for their discussions. After the school fire in 1906, however, a new policy initiated by the societies permitted the girls to engage in all the activities on an equal basis with the boys.[178]

What library the school possessed was built by the literary societies. This library began with an old dry goods box and a few used books but by the time of the fire in 1906 each society had collected nearly a thousand volumes.[179] The fire destroyed most of these, however; in 1915 the Calliopean Society could boast of a library of only "several hundred volumes.”[180] By 1925, however, the two societies possessed a combined library of approximately 3,000 volumes. This growth was made possible by monetary donations and private collections that were given to the societies, like that of a wealthy Florida planter, who contributed a valuable library of several hundred volumes.[181] In addition, the college on its own acquired a library of 2,000 volumes, one-half of which was religious in nature, consisting of reference works, commentaries, books of sermons, biographies of preachers, and related works.[182]

The literary societies not only provided the students with the bulk of their outside activity, but were also looked upon as being "an important additional means of culture” for the students, and were considered as important as any other feature of the college. It was through these societies that students could secure "Independent thought, critical investigation, and ready utterance. . . Besides, it begets a confidence students so much need, and wear off the embarrassment [sic] they all feel when appearing before an audience, to give utterance to their thoughts,[183] Because of the experience gained in debating and public speaking, many of Burritt's students went on to achieve notable careers in public office.[184]

Shortly after Carnes arrived at Burritt, Dr. Thomas Wesley Brents, physician and a member of the Church of Christ,[185] moved to Spencer and suggested the ideas of expanding the facilities of the college in an effort to restore the school's prestige and prosperity. It was Brents' belief that the school was unstable because it was not meeting the academic needs of the students, due to the conservative policies of the administration. Brents proposed the initiation of a fund drive to help build a new campus, purchase additional land, and buy new equipment for the school. Impressed with Brents' enthusiasm and suggestion, the trustees with Carnes' approval employed Brents to engineer a drive for the sale of stock for the stated purpose of securing funds to erect “a new Burritt College.” Brents proved successful as a fund raiser, for within a few months he sold all the stock which the charter permitted.[186]

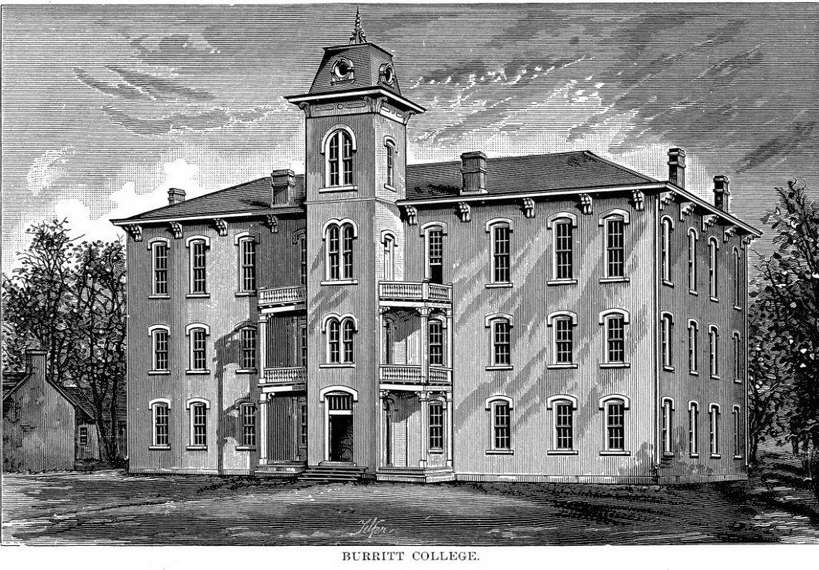

A new administration building, the center of the proposed "new school," was completed in 1878. A magnificent structure, it was three stories high, contained seventeen rooms, and had a main hall eighty by fifty feet. Described as "large, commodious, and elegant,[187] the edifice had a protruding tower centered in front, extending a full four stories, with a small portico attached on both sides for the first two floors. It clearly dominated the campus, being located at the very front with the smaller dormitories situated just to its right.

The building cost $12,000, whereas the old buildings, including the three small dormitories, were worth from $7,000 to $8,000. J.R. Ryan of Chattanooga was architect for the building, while O.S. Wright of Nashville served as contractor.[188] In addition to the new building, fifteen acres of ground were added to the ten acres which composed the campus.[189]

The expanded campus was to be the nucleus of a "brotherhood school."[190] In order to facilitate more efficient efforts toward this end, Elijah Denton deeded one-half of his stock in Burritt to Brents so that Brents could personally direct the fund drive.[191] To persuade more people to contribute to this drive Brents proposed to make Burritt a religious school.[192] This strategy paid off, for more than $25,000 was raised in cash and pledges from members of the Church of Christ in Middle Tennessee and elsewhere.[193]

When the new building was completed in 1878, Brents, who now had a controlling interest in Burritt, demanded that Carnes resign and that he take Carnes' place. This caused a great sensation among Burritt supporters, for Brents' administrative experience was at best limited.[194] Carnes' friends were shocked "with astonishment and indignation" at Brents' demands. Many openly protested to Brents, while a few of the trustees expressed their opposition by resigning their positions.[195]

Finding himself in a quandary, Brents attempted a reconciliation with Carnes' faction by proposing that Carnes remain on at Burritt in a teaching capacity. Carnes declined the offer, however, and severed all ties with the school at the end of the spring session in 1878 to become president of Waters and Walling College, a new school at McMinnville supported by members of the Church of Christ.[196]