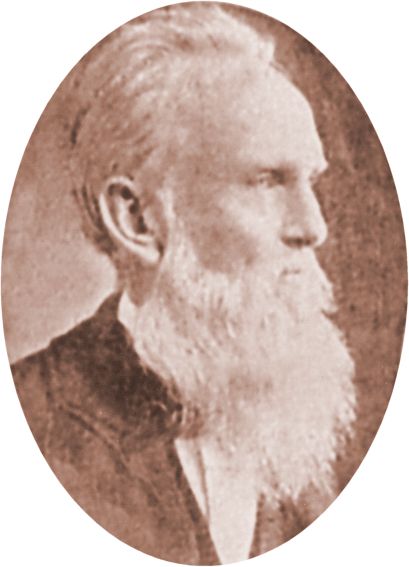

Justus McDuffie

Barnes:

The Heritage Of Alabama's Restorer

This year is the 150th anniversary of the birth of Justus McDuffie (""Mack"") Barnes who was born on February 10, 1836 in southern Montgomery County, AL. His heritage is the strength of the churches of Christ in South and Central Alabama. Though he was educated under the feet of Alexander Campbell at Bethany College (from which he graduated in 1856 with an A.B. and received an A. M. in 1861), he fell under the influence of David Lipscomb in the post-war period. As a result, J.M. Barnes became the single most important representative of restorationism in Alabama. His influence is particularly important in three respects.

His Conservative Heritage

The progress of the conservative wing of the restoration movement in Alabama owes its present condition to the efficient work of J.M. Barnes in the last four decades of the nineteenth century. Though closely associated with the Millenial Harbinger immediately after the war, he quickly saw more of a common spirit in the Gospel Advocate edited by David Lipscomb. For a time he wrote a column in the Advocate under the heading ""The Little Man.""

Lipscomb and Barnes developed a close relationship through their mutual concerns, Barnes' meeting work in Tennessee, and his articles (as well as occasional news items) in the Advocate. They stood together against missionary societies and instrumental music. More than any other man, Alabama owes its conservative heritage to J.M. Barnes who opposed these innovations from the very beginning. When an attempt was made to establish a society in 1865 at Pine Apple, AL, Barnes was there to oppose it and the effort failed. When the Alabama Missionary Society was finally established in 1886 at Selma, Barnes was there to oppose it. When an instrumental group attempted to establish a congregation in Montgomery in 1898, Barnes and his son, E.R. Barnes, persuaded them to give up the work. Even when the instrumental group was established in 1908, their membership did not total more than seven in 1911. Barnes' conservativeness is reflected in the fact that he wrote for the Firm Foundation, American Christian Review, J.A. Harding's Christian Leader and the Way, and the Word and Work while it was still in New Orleans.

However, in matters of controverted points within the southern brotherhood, Barnes generally stood with Lipscomb over against the Firm Foundation and other detractors. Three points substantiate his closeness to the Advocate editor. Lipscomb believed that a Christian should not participate in the civil affairs of government. Barnes, independently of Lipscomb, arrived at the same conclusion during the Civil War. Barnes, like Lipscomb, only voted in one national election--1860. On a second front, Lipscomb opposed participation in war and Barnes stood with him. During the Civil War, Barnes was drafted by the Confederacy, but was quickly released as a conscientious objector because he did more preaching than fighting. On a third front, Lipscomb did not believe that every Baptist had to be re-immersed if his motive was to obey God rather than join the Baptist Church. Barnes, again independently, stood with Lipscomb. His articles in the Advocate establish this as well as the church roll of the Strata Church of Christ where Barnes ministered (1869-1881).

The Strata records clearly demonstrate that in any given year some might be immersed, some might be disciplined, some might confess, some might be restored and others might ""come from the denominations."" Barnes was calling men out of their sectarianism, but he was not, in his view, forcing them to obey the gospel twice.

Thus, Barnes held the line on innovations and was not pressured by others into changing his convictions on issues of interest in the late 1800s. This conservative heritage, preserved in the likes of Rex A. Turner, Sr., is due in large measure to the work of Justus McDuffie Barnes more than any other man.

His Educational Heritage

Barnes was a leader in education in Central Alabama. When he returned from Bethany in 1856, he established Strata Academy on his father's plantation. It offered an elementary and secondary education. The school continued except for two interruptions, the war years and the depression of 1873, till it was moved to Highland Home, AL in 1881 as Highland Home Institute. The school was incorporated as Highland Home College in 1889 and offered the A.B. degree. Barnes left the school in 1898 to establish a secondary school in Montgomery and serve the church there, but Highland Home College continued till 1916. Before it closed, the school was reorganized as a Bible College (1910), and Barnes served on the board of the institution.

After moving to Montgomery, Barnes established Barnes School which continued operation until 1942. Since ""Mack"" wanted to devote his last years to evangelistic work in Alabama and Texas, his son, E.R. Barnes, took over the principalship of the school in 1901. Many of Alabama's greatest politicians, doctors and lawyers were educated at one or more of Barnes' schools. The religious atmosphere of Alabama is also indebted to J.M. Barnes since he educated any man who wished to be a preacher free of charge.

His influence reaches into the present. In the same year that the Barnes School ceased operation, the Montgomery Bible School, under the direction of Leonard Johnson and Rex A. Turner, Sr., was established in Montgomery, AL. This school, once Alabama Christian College and now Faulkner University, was possible only because of the previous efforts at education, whether specifically Christian or not, by the Barnes family. In 1967 Alabama Christian School of Religion was established by the board of ACC as a separate institution to offer the B.A. degree while ACC sought accreditation as a Junior College. Today Christian education is offered at both the undergraduate (at Faulkner University and a junior/senior program at ACSR) and graduate (at ACSR) levels in the wake of the early efforts of the Barnes family in Central Alabama.

His Evangelistic Heritage

Barnes was an active church planter. Given his relative wealth (he inherited a plantation from his Father in 1861), he was able to travel as an evangelist throughout Alabama as well as in every southern state (including Texas) except the Carolinas. Like most second generation pioneers of the restoration movement he was involved in many protracted meetings (ranging from four to eight weeks in length). In this way he planted churches all over the state of Alabama and other southern states. At his death in 1913 Barnes had been a preacher of the gospel for 51 years (beginning in 1862).

In particular, Barnes is remembered for beginning the work of the churches of Christ in both Montgomery and Birmingham. Around 1879 there were both Black and White christians in Montgomery. Barnes had been preaching occasionally in the city for sometime. In 1888 the church began meeting as an organized body on Herron Street in a building largely financed by Barnes. When he moved to Montgomery in 1898, he served Montgomery's first church as its minister. He also provided the funds for the purchase of the synagogue on Catoma Street in 1901. The Catoma Street Church of Christ where George Herring ministers still meets in that same facility. When Catoma hired its first minister on a stipulated salary in 1910, Barnes began work for another congregration he had planted called West End (disbanded in 1981).

The beginning of the work in Birmingham is due to J.M. Barnes (dating as early as 1876) but its development and expansion is largely due to John T. Lewis (1906 graduate of Nashville Bible School). Barnes and Lewis held meetings together in the Birmingham area and developed a close relationship. They are responsible for the beginning of the West End congregation in Birmingham. In one meeting with John T. Lewis in Childersburg near Birmingham the father of Emily Cleveland Cliett was immersed. In 1918 Emily became the wife of B.C. Goodpasture, the lamented editor of the Gospel Advocate from 1939 to 1977. Another daughter, Mildred Cliett, later became the wife the beloved J.M. Powell. Their mother was a sister-in-law to J.M. Barnes and had attended Highland Home College.

While serving the church in meetings and local work, he did not feel comfortable with being paid for his efforts. He never made a stipulated salary a condition of his labors, and he never received a stipulated salary. In fact, J.M. Garrett recalled that when Barnes received $92 for week-long meeting in Tennessee, he commented that he would never return to Tennessee for a meeting since it would be injurious to himself and the church. Garrett also stated that Barnes never received more than $300 for his evangelistic work in any given year. This is indicative of the sacrificial attitude of the restoration movement's pioneer preachers.

In conclusion, let it be said that the past is studied so that it might teach us about the present. The heritage which has come down to us from Justus McDuffie Barnes is a good one. It motivates, guides and sustains us. We need not renounce our conservative, educational and evangelistic heritage. However, it must be remembered that one of the things which we learn from the past is its mistakes. In this light, the Bible and the Bible alone must judge the efforts, views and heritage of J.M. Barnes. This challenge must be accepted and pursued by all restorationists, and not just Alabamians.

-John Mark Hicks, Gospel Advocate Vol. 128 #9 (May 1, 1986), pages 276,277

This Monument Lies In The Fair Prospect Cemetery Located On

Hwy 331, About 30 Miles South Of Montgomery Alabama

Dedicated To The Work Of J.M. Barnes At Strata And

Highland Home Schools

ReturnTo J.M. Barnes Main Page

![]()