The Cave Affair:

Protestant Thought in the Gilded Age

By Samuel C. Pearson, Jr.

![]()

On December 8, 1889, under the headline "Clerical Sensation" the St. Louis Republic printed a recent sermon by the minister of the city's Central Christian Church. According the the Republic the sermon had "provoked an endless amount of discussion and gossip last week, and was severely denounced by at least one minister." Thus commenced what came to be known as the Cave affair, a controversy over the reverend Dr. Robert Cave's theological modernism, which excited and entertained citizens of St. Louis for several weeks, provoked a schism in Cave's congregation and establishment of the Non-Sectarian Church of St. Louis, and stirred a controversy over heresy in the newspapers of the Disciples of Christ. The affair also won Cave one brief citation as his denomination's "first modernist" in William R. Hutchison's The Modernist Impulse in American Protestantism. Aside from this small note Cave appears to have been relegated to the domain of denominational history where attention has focused less on the man and his ideas than on the impact of the affair within a denomination on the eve of its division into Christian Church and Churches of Christ. The inevitable result of this focus on impact rather than event has been to render Cave a mysterious figure who suddenly appeared among the Disciples of Christ, stirred a controversy over modernism, and as suddenly disappeared. Like the priest Melchizedek, Cave seems to have neither father nor mother nor line of descent. Yet this depiction is entirely inaccurate and serves only to obscure a fascinating personality whose biography is instructive with respect to forces at work within Protestant thought in the gilded age.

Robert Catlett Cave (1843-1924) was actually a birthright Disciple of Christ. He was the second son and third child born to Robert Preston and Sarah Lindsay Cave of Orange County, Virginia. The county, almost entirely rural, had been a center of Baptist activity in Virginia since John Leland's ministry there between 1776 and 1791. The separation of the followers of Alexander Campbell from the Baptists about 1830 promptly led to the formation in Orange County of churches of the new denomination known variously as the Christian Church, Church of Christ, or Disciples of Christ. To one of these, the Macedonia Christian Church, both the Cave and the Lindsay families belonged. The profound influence of this congregation on the Cave family is suggested by the fact that all three sons and the one son of the daughter who lived to maturity became disciple ministers.

The family was relatively prosperous, owning over four hundred acres of farm land as well as several slaves. Their home was then and remains an impressive local landmark. The county had no public schools, and Robert Cave, his brothers, and his sister probably received their early education in the home. In any event it may be presumed that here in rural Virginia in a county whose favorite son was James Madison they early encountered Jeffersonian and Madisonian political philosophy. Though Sarah Cave died in 1852, her death seems not to have left Robert with an extreme or abiding sense of loss. His early experiences in home, church, and community were later fondly remembered and apparently exercised their influence in shaping Cave's commitment to agrarian democracy, state's rights, and religious freedom as well as his lifelong affection for the place and people of his youth.

It is scarcely surprising that in 1859 at the age of sixteen Robert Cave should have been sent to Bethany in the northwest corner of the state to study in Alexander Campbell's college. Established in 1840, the school had earlier reflected the vigor and zeal of its founder and had won a reputation throughout and beyond the denomination. Yet times could not have been less propitious for an entering student in Campbell's academy. Campbell himself was in declining health, and Cave's first year proved to be Campbell's last of active labor in the college. In October of Cave's freshman year John Brown's raid on nearby Harper's ferry threw Virginia into panic and the entire nation into political turmoil. Campbell had struggled valiantly but ineffectively to stem the tide of sectionalism among his followers only to see his efforts scorned alike by North and South. Even Campbell's own family was torn by the issues dividing the nation, and Campbell recognized in the growing probability of conflict in the demise of his millennial expectations for America. Both the vigor and the optimism which had sired the college waned; and if anything positive occurred in the classrooms of Bethany in 1859-60, it must have been a miracle.

Yet Cave's second and final year was far worse. It commenced with the election campaign of 1860 which left the nation torn by talk of secession and civil war. In the midst of the nation's uncertainty Cave spent the holidays in Orange County where his father died on New Year's day, 1861. Though he probably returned briefly to Bethany, Cave soon withdrew to enter the military service. The college matriculation book bears the cryptic marginal notation "returned home" Thus at eighteen years of age Cave had completed his formal education; he never returned to college though he had excelled academically and was granted an honorary degree by his alma mater following the Civil War.

What Cave learned at Bethany is hard to say. Campbell's morning lectures to the class of 1859-60 were subsequently published, but they are unexceptional. The editor of the lectures admitted as much in observing that they "frequently fall below the standard of his Lectures during the previous sessions" and that their greatest value will derive from "endearing associations" Cave's commitment to the Disciples of Christ preceded his matriculation at Bethany and may be presumed to have accounted for rather than to have resulted from his study there. Furthermore, Cave remained throughout his life intellectually heir as much to Jefferson as to Campbell. Yet some of his writing for the Apostolic Times during the 1870s bears an unmistakable Campbellian flavor as does his propensity to enter his lists with Baptists and Catholics. Beyond this, if the purpose of a college education is the development of a lively imagination and sufficient skills to pursue questions to solution, Robert Cave may have been well served during his short tenure at Bethany. Through a long life he read widely and perceptively and maintained a vital interest in belles lettres, history, national affairs, and religious scholarship.

![]()

-"in this Orange County company,...half of the casualties occurred before the Seven Days Battle"-

Virginia's entry into the Civil War found Robert Cave a private in the Montpelier Guard, Company A, 13th Infantry, Army of Virginia. Having promised his father "that [he] would serve Virginia as long as she might need [his] service," Cave enlisted on April 17 as soon as Virginia voted secession. Both of his brothers and many of his friends and neighbors served in this unit recruited largely from Orange County. The four years of adversity, terror, and loss proved to be a horrible coming of age for a bright and sensitive youth; but the exorbitant demands of war proved ennobling as well. Cave would certainly have understood and concurred in the observation of his contemporary, Mr. Justice Holmes, who had left Harvard to fight for the Union in Virginia, that "the generation that carried on the war has been set apart by its experience. Through our great good fortune, in our youth our hearts were touched with fire. It was given to us to learn at the outset that life is a profound and passionate thing."

Though all three brothers survived the war, each was wounded. The company itself was decimated. While Robert Cave was transferred to the Signal Corps during the course of the conflict and while there were undoubtedly other isolated transfers, the terrible-fact remains that in this Orange County company, which Cave estimated entered the war with about a hundred officers and men and which received an additional fifty in reinforcements, twenty-seven were killed; and most of the remaining were wounded. Half of the casualties occurred before the Seven Days Battle in the summer of 1862, and Cave recalled that thirty-five more were killed or wounded in that struggle alone. The company fought at Harper's Ferry, Bull Run, Winchester, Cross Keys, Port Republic, Fredricksburg, and Manasses. Reflecting the exhaustion of soldiering, Cave observed in his memoirs that as they marched wearily toward Winchester "the rising sun bathed the summit of the distant Blue Ridge in splendor, but my eyes were too heavy to appreciated its beauty." The same memoirs record the rejuvenating power of momentary victory and the light-hearted banter of the barracks. Yet the dominant mood is one of seriousness and, after Gettysburg, of foreboding. Cave was in Winchester when the Confederate survivors of Gettysburg straggled through. He described them as "more ragged and unkempt, more worn and haggard, more slow in their movements, and more grave and cowed; they seemed rather to be conscious of adverse fortune and grimly determined to face it bravely. But they looked dog-tired; and, as some one standing near me said, they seemed to be ashamed of coming back to their friends without having accomplished all that was hoped for."

At New Market, his line of communication with his own army broken by the Union advance, Cave learned from a "ragged, dust-covered, and tired-looking man, mounted on a lean and tired-looking horse," of Lee's surrender. With some comrades from the New Market outpost he headed south to join Johnston, but upon reaching Staunton the band learned of Johnston's surrender. With that news, recalled Cave, "our last hope died. The end had come, and with a heavy heart I turned my horse's head eastward and rode home." Mindful of a soldier's duty, he added, "I had enlisted for the war; the war was over; the term of my enlistment had expired." The following month Cave signed the parole at Louisa Court House a few miles south of his home.

From this youthful experience

of struggle, sacrifice, and defeat Cave gained attitudes which marked the

rest of his long life. In retrospect he concluded that the Confederate

cause was lost before the first shot was fired. The outcome was determined

by population and industry, not by ideology or devotion. Yet to this lost

cause in its constitutional dress of state's rights and limited government

and to a Jeffersonian laissez faire economic system based in agriculture

and small business Cave remained committed into the twentieth century. The

result of the war experience for Cave was a profound awareness of the

discontinuity between truth and  power or right and might which left him

ill at ease with the progressive optimism and positive thinking of so many

Americans in the gilded age. Perhaps from this war experience rather than

from the teaching at Bethany College, which was reputed to be Lockean,

Cave became a philosophical idealist who posited innate ideas and elevated

the realm of ideas to a level of greater significance than that accorded

the realm of empirical reality.

power or right and might which left him

ill at ease with the progressive optimism and positive thinking of so many

Americans in the gilded age. Perhaps from this war experience rather than

from the teaching at Bethany College, which was reputed to be Lockean,

Cave became a philosophical idealist who posited innate ideas and elevated

the realm of ideas to a level of greater significance than that accorded

the realm of empirical reality.

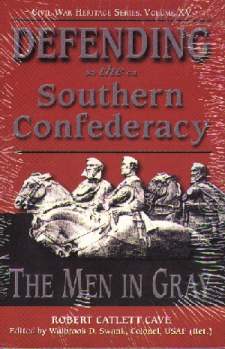

The lasting significance of Cave's early life in antebellum Virginia and of experience as a Confederate solder became fully apparent in the last decade of the century. As a generation of veterans was rapidly dying, Confederate and Union monuments were erected in large numbers. One of the most impressive was erected to the memory of soldiers and sailors of the Confederacy in 1894. On the occasion of its dedication, Cave, a native Virginian, a veteran of enlisted service, and by then a former Richmond minister, was chosen to give the address. Delivered on Memorial Day, it was a defense of the lost cause itself, a vindication not simply of the bravery of those who struggled and died but also of the cause for which they labored. Eloquent and impressive, the speech was printed in its entirety in the Richmond newspaper and subsequently in pamphlet and in newspapers throughout the country. One newspaper account described the speech as an expression of "sentiments, seemingly long-bottled up" and as "ample evidence of the fact that the efforts of the reconstructionists had availed nothing in [Cave's] case." The description was accurate; for Cave might, not right, had been the victor. Appomattox was not, declared Cave, "a judgment of God....Instead of accepting the defeat of the South as a divine verdict against her, I regard it as but another instance of 'truth on the scaffold and wrong on the throne'" Similar sentiments characterized Cave's 1911 address to the annual meeting of Confederate veterans; and in that year he published The Men in Gray, a volume containing the Richmond address, a narrative of the controversy which followed that address, and additional chapters arguing the legitimacy of the Confederate constitutional position. His views are summarized in an inscription Cave penned for the Confederate monument placed in Forest Park by the St. Louis chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy in 1914:

To the memory of the soldiers and sailors of the Southern Confederacy, who fought to uphold the right declared by the pen of Jefferson and achieved by the sword of Washington. With sublime self-sacrifice they battled to preserve the independence of the states which was won from Great Britain and to perpetuate the constitutional government which was established by the fathers. Actuated by the purest patriotism they performed deeds of prowess such as thrill the heart of mankind with admiration

![]()

-"must be so non-exclusive that it can include all Christians"-

During the War Cave married Fannie Daniel, a neighbor whose family was also active in the Macedonia Christian Church. The first of their ten children was born in 1864, and it was thus to a growing family that Cave returned at war's end. He entered briefly into business but was soon encouraged by the Macedonia Church to become its minister. Ordained in 1867, Cave served this congregation and other nearby churches of his denomination until 1872. While he was still in his twenties Cave's reputation for eloquence and effectiveness spread, and in the latter year he was employed by the editors of the Apostolic Times, a denominational journal published in Lexington, Kentucky.

The most apparent characteristic of the Apostolic Times is its contentiousness. Published during the years when Cave's denomination was splintering, The Times was dominated by J. W. McGarvey, the conservative president of College of the Bible and ardent opponent of innovation whether in the area of biblical criticism in the classroom or of instrumental music in worship. The Apostolic Times missed no opportunity to identify and condemn error whether of other denominations or of the brethren. Though sometimes directing its attack against conservatives within its own ranks who too literalistically applied the scriptures in defining an apostolic order, the paper more generally attacked liberals who were attracted to the urbane and ecumenical Protestantism of the Northeast.

Cave was hired to manage the office and to edit departments of Christian family and of religious news. While the former department was innocuous enough, the latter required that he examine all available religious publications in order to provide readers of the Times with adequate information concerning general religious developments. Clippings reprinted in the Times during Cave's tenure with the paper reveal that in addition to other denominational papers and national literary magazines Cave regularly read papers reflecting a wide variety of religious viewpoints. Most important among these for Cave's own religious development were the Congregational Independent and Christian Union and the Unitarian Christian Life. While much of this literature was quoted to be refuted or to illustrate dangers attending the positions of rival religious groups, many of the criticized views of the Protestant liberals later reappeared as Cave's own. Thus from the Christian Union Cave clipped an editorial "in favor of making not sectarian creeds, but the essentials of Christianity the basis of Church membership." While the sentiment expressed was ambiguous enough to gain limited endorsement from the creedless Disciples, this was not true of the sentiments of J. G. Chinn of Lexington, Missouri, who, according to the Times, advocated that a Christian should "believe as you please and do as you please, provided you are honest." Cave vigorously denounced what he deemed to be in the Unitarian position that a person may be baptized upon making a confession of faith "as he understands it, while the church judges that he is not a proper subject of that ordinance until he can make the confession as she understands it."

On the other hand, Cave reflected a more liberal temperament in launching an attack upon the methods and efficacy of revivalism while at the Times. He observed that "what are termed revival meetings may prove a curse, instead of a blessing, to both the church and the world." In a magazine dominated by controversy and heresy hunting, Cave seems also to have been a voice of moderation. In an editorial entitled "The Christ-Spirit in Us" Cave insisted that "conversion is something more than the assent of the mind to the truth that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of the living of [sic] God, and the burial of the body in water in obedience to his command." This something more Cave identified as the implanting of the Christ-Spirit in the individual. He soberly confessed that "when I call to mind the jarring and wrangling and strife that prevails to such an alarming extent among those who profess to be Christians, I cannot but think that many are deceived in regard to this matter." In words which may well have been addressed to his co-editors Cave cautioned: "We advise no compromise with error, either in our own ranks or in the ranks of sectarianism, and we have no sympathy with that charity--falsely so called--which seeks to make apologies for it. But we would not rashly prefer charges against our brethren; for justice and right demand that guilt shall be proved before sentence of condemnation is pronounced." Cave agreed with his fellow editors that the true church "must be so non-exclusive that it can include all Christians," and that no denomination was sufficiently inclusive. Yet while agreeing that their own denomination had struggled to avoid sectarianism, Cave lacked McGarvey's conviction that the effort had been successful. He warned that "men have a peculiar fondness for their own views, and we should be very cautious, lest we practically exalt some cherished opinion of our own into a test of fellowship." In ecclesiology as elsewhere Cave's ideal seems to have been transcendent and immaterial rather than the all too empirical reality of the majority of his fellow Disciples.

Yet neither Cave nor his colleagues at the Apostolic Times had an idea of the theological destination to which he was headed in the 1870s. From his arrival in Lexington in 1872 Cave had preached in the historic Christian Church in Georgetown, and at some point he moved to that community. The increasing demands of the Georgetown ministry and the difficulties of commuting to Lexington rather than theological disagreement led to Cave's amicable withdrawal from the editorial board of the Times in 1875.

May of 1876 found Cave in Hopkinsville as the newly elected president of South Kentucky Female College, a denominational institution, where he remained until 1883. Cave taught English and literature as well as philosophy and became acquainted with the work of post-Kantian theological reconstruction in Germany. He also continued reading liberal magazines with which he had become familiar. Cave's scrapbook includes a long review of Edward Beecher's History of Opinions on the Scriptural Doctrine of Retribution, published in 1878, which traced the idea of universal salvation to the church fathers. The scrapbook also includes Cave's own copy of Jefferson's abridged New Testament which he apparently prepared from the table of texts provided in Henry S. Randall's The Life of Thomas Jefferson.

In a denomination whose polity was congregational and which lacked virtually all rudiments of associational structure, Cave seems perennially to have been torn between his eloquence and love of preaching and the pastorate on the one hand and his ambition to exercise a wider influence available only through newspapers and institutions on the other. Just as he had found a pulpit in Georgetown while at the Times, so he found other pastorates while at the college. He served the Hopkinsville and Cadiz Christian Churches for a time and by 1880 had become minister of the Church Street (later Vine Street) Christian Church in Nashville. Cave apparently commuted by rail to Nashville and shared the responsibility of the church with his brother, R. L. Cave, who remained in Nashville as pastor of the church for many years.

Characterized by a recent historian as "the only [Disciple] minister in Tennessee who voiced liberal tendencies" at this time, Cave was apparently far from outspoken about his changing ideas. However, his scrapbook for the period contains a clipping discussing the views of Felix Adler, found of the Ethical Culture Society, and another exploring the problem of whether a Unitarian, led through practicing the Unitarian beliefs, was bound to "step down and out" of the denomination. Thus it is probable that Cave was considering seriously the challenge posed by liberalism. Yet the only two sermons extant from Cave's Nashville ministry were preached in 1883 in response to statements made at the consecration of Catholic bishop Joseph Rademacher. These sermons reveal a Protestant clergyman arguing the case against Catholic claims of ecclesiastical authority on traditional grounds. On the other hand they also reveal an impressive grasp of church history and a familiarity with the debate waged within the Catholic church over the dogma of infallibility at the time of Vatican Council I.

Cave left Richmond to accept a call to the Central Christian Church of St. Louis. St. Louis was a dynamic city; and though the church was relatively weak, it appeared to have a promising future. Central Christian Church had just occupied a new but heavily mortgaged building on the bustling west side of the city, was the most liberal of Disciple churches in the city, and had within its congregation several prominent figures including James H. Garrison, the editor of a denominational weekly, the Christian-Evangelist, and Dr. Robert M. King, a distinguished physician and Kentuckian who had known Cave in Hopkinsville. Upon receiving the call, Cave was reluctant to leave Richmond. He first asked for time for consideration and then for written assurance that he would have freedom to preach his convictions. Apparently satisfied, he was in St. Louis by December, 1888.

![]()

-a church "as free as the universe"-

Cave's first year at Central Church passed quietly. No notice of his sermons appeared in the local press, the church's board minutes are devoid of ideological controversy, and the mortgage remained a consuming problem. In late September Garrison confided to his journal an uneasiness with Cave's sermon of September 29 in which he had identified the "brethren" whom Christians are to love with "all men" but if others were concerned there is no evidence. However, Cave became a prominent public figure on December 8, 1889, when the Republic printed his sermon of the previous week together with commentary from other clergymen. In this sermon entitled "No Man Hath Seen God" Cave introduced a few of the more obvious implications of biblical criticism. He suggested that scripture contains not the inherent and unalterable word of God to man but rather the record of man's gradual and incomplete, fallible and evolutionary discernment of the will and nature of God. He specifically challenged the scriptural claim that God commanded Abraham to sacrifice his son, claiming that such a command would have violated the nature of God and was morally abhorrent. These views may have been commonplace in some quarters, but in St. Louis they constituted a "clerical sensation." The newspaper account included the criticism of another Disciple minister, O A. Bartholomew, and the judgment of a local Baptist pastor that Cave was "verging on Ingersolism" but added the interesting editorial observation that Cave's magnetic eloquence...had excited no little jealousy" among other of the city's clergy.

Having created general excitement through its initial story, the Republic maintained and satisfied community interest by sending a stenographer to Cave's church and printing his sermons for several weeks. The denominational press quickly took notice of the St. Louis affair. While its criticism was of little concern to Cave or to his congregation which, according to Disciple practice, enjoyed virtual autonomy, it was a serious threat to Garrison whose newspaper was engaged in vigorous competition for a denominational readership. As an officer of the congregation Garrison was compelled to comment on the Christian-Evangelist. He initially recommended moderation, but when Cave, true to his idealist philosophy, declared that one could believe in the "essential Christ" whether believing "him to be divine or human, historic or fictitious," Garrison condemned Cave and engineered his withdrawal from the congregation. Critical comments also appeared in Chicago's Christian Oracle, Cincinnati's Christian Standard, which had absorbed the Apostolic Times, and Nashville's Gospel Advocate. Cave submitted his resignation to Central Church on December 27 though it was not accepted until January 5, 1890. By the end of December members were withdrawing from the congregation to form a new West End Christian Church on what one of them termed "the old-line Campbellite basis" of absolute congregational autonomy. Cave accepted a call from this group and preached his first sermon in a rented hall on January 13, 1890. Two weeks later in response to continued denominational criticism both Cave and the congregation renounced all denominational affiliations, and the congregation became the Non-Sectarian Church of St. Louis.

Though it identified with a national Non-Sectarian movement, the St. Louis church had a particular character shaped by Cave's personality, theology, and denominational background. Erecting a building on one of the city's most fashionable west end boulevards, the congregation maintained a vigorous ministry on the liberal fringe of Protestantism for a decade. After Cave's retirement the church affiliated with the Christian Connexion, a denomination historically and ideologically closely akin the to Disciples. The character of Jesus was exhibited as the model for reshaping individuals and society in the face of a perceived decline of orthodoxy. A religion without priests or creeds and a church "as free as the universe" were the objectives of the society. Cave insisted that his congregation was to be "practically, as well as theoretically, non-sectarian. [and to] receive into fellowship all who accept Christ and follow him according to their own conception of him and his teachings..." He declared his church to be "for Christ against creeds; for rational faith against blind credulity; for spiritual religion against lifeless formalism...for the final redemption of all against the failure of God's purpose and work."

Joseph Fort Newton, who served for a time as Cave's assistant, later remembered the church as "a shrine of simple faith and good fellowship. It was positive both in its message and its methods, an appeal to the Church outside of the church, not a revolt against faith but an affirmation of the things really essential to religion as it stands in the service of life." He described Cave as "a new species of preacher. A man of rare personal and intellectual charm...[who] set forth the life of Jesus, His spirit, His teaching for everyday living, His office as Savior of man from himself, from brute fact and dark fatality."

![]()

-"Even the Bible lacks authority independent of reason"-

The Republic continued to publish Cave's sermons regularly until mid-March, 1890, when interest apparently began to wane. Thereafter his sermons were occasionally reported as when he preached in the Church of the Messiah, when he stirred a storm of protest by baccalaureate sermon at the University of Missouri, or when he returned from a trip to Europe and the Holy Land. A monthly journal, the Non-Sectarian, was inaugurated by Henry R. Whitmore, a member of Cave's church, in January, 1891. Before the magazine's demise in December, 1895, no less than twenty-five additional Cave sermons appeared in print. From these sermons and from an unpublished manuscript entitled "The Immanent God," Cave's theology may be reconstructed.

There is a remarkable sameness to Cave's sermons. Regardless of title or text the sermons inevitably turn to a quite limited range of very specific questions. Among these are the central questions posed for Christianity by the Enlightenment: the relationship of faith to reason, theodicy, and the relationship of religion to morality. His position on these themes was consistently rationalistic and reflects the influence of the American Enlightenment. Cave also focused attention on Christology and ecclesiology, topics probably thrust upon him by his background among the Disciples of Christ. Yet his treatment of these doctrines may easily be subsumed under the general questions of the conception of God and the universal scope of salvation Cave reflected the influence of nineteenth century philosophy and American transcendentalism as well as of an earlier Enlightenment rationalism.

Central to Cave's homiletic endeavor was the conviction that orthodoxy had been routed by modern thought and that the church had but two alternatives, to change or die. Observing that "the world is rapidly turning away from the church of dogma and form," Cave declared that "only five per cent of the young men of America are members of the church, that only fifteen per cent, including the church members, attend church regularly; and that seventy-five per cent never darken the church doors." The reason insisted Cave, is "because they can no longer believe, and find satisfaction in the theological theories and schemes and ceremonies which the church teaches and requires men to accept. The church no longer has a gospel for them." Cave characterized the age as a "time of religious unrest" in a baccalaureate sermon at the University of Missouri, and in the heat of controversy he reminded his congregation of Tennyson's claim that "there lives more truth in honest doubt, believe me, than in half the creeds." Thus, though recognizing his significant departure from orthodoxy, Cave regarded himself as a defender of Christianity. In phrases reminiscent of Jeffersonian liberalism Cave presented the Non-Sectarian case:

We claim that we have freed ourselves from many superstitions and errors still taught by the Church, and planted ourselves on higher ground. We claim that we have come nearer to the truth as it is in Christ Jesus; that we have truer and nobler conceptions of God, and of Christ, and of worship, and of sin and salvation. We claim that instead of weakening moral obligation, we place morality on a more rational and permanent foundation, making it, instead of obedience to the arbitrary will of a supreme ruler whom we must obey to avoid his vengeance, conformity to the eternal law of right which is written in man's being and in the constitution of the universe, and to which we must conform because it is right, and because conformity to it is necessary to the preservation and development of true, noble, and self-respecting manhood. We claim that, instead of opposing true religion, we have separated the religion of Jesus from the traditions and dogmas and forms imposed upon it..."

The tension between faith and reason was easily resolved for Cave who believed that "in [man's] power to discern the right and his sense of obligation to do the right he is furnished with a guide to lead him onward and upward to the true end of his being." Man's "authoritative rule of right is within himself...His reason and conscience are the supreme judges by whom whatever is offered to him as true and right, even though it may claim to be a revelation from God, must be tried, and approved or condemned." Cave's application of this principle in criticism of the biblical narrative had inaugurated the controversy. In response to criticism on the Non-Sectarian Church's creedlessness, Cave responded that thinking for himself "is not only man's right but his duty...Only as man uses his liberty of thought, only as he is mentally independent and freely and fearlessly follows the light, is it possible for him to rise up to the highest place of intellectual and moral excellence." Even the Bible lacks authority independent of reason, insisted Cave, and therefore "we leave every man free to read and study the Bible for himself, and reach his own conclusions in regard to it, and follow the light which his own soul sees reflected from its pages."

The rationalistic element in Cave's thought is also apparent in his description of divine providence. Sweeping aside the pietistic image of a God who dabbles in human affairs in response to supplication, he affirmed a trust in God's regularity and reliability. God, wrote Cave, "is a God of law. He works by and through nature alone; and we cannot reasonably trust in him to do what nature will not do. A thousand Moodys may pray for the safety of a steamer disabled in mid-ocean, but without skillful management, and favorable concurrent circumstances--without natural causes adequate to produce the result--the steamer will never be saved from the engulfing waves." Yet if Cave's God was not the arbitrary despot envisaged by many a revivalist, neither was He the remote watchmaker of the deist. God, for Cave, worked no less through the human heart than through natural law. Thus though a perfect deity could not be changed by prayer, prayers might "give Godward direction and exercise to our powers of mind and heart, and thus, naturally, draw us into harmony with the Father..." In "The Immanent God" Cave responded to "the opinion that the world-wide war, with its frightful cost of blood and treasure and its horrifying outrages, being utterly incompatible with the old faith in a benevolent Ruler of the universe who is able to bring about anywhere and at any time such conditions as he may desire, must compel the church to reconstruct her theology." His solution, suggested in earlier sermons, was a God "limited by his own nature" who "always acting in harmony with his attributes...can, sooner or later, unfailingly accomplish his purposes." Thus God, though unable to prevent the evil and suffering of war, "can and will educe good from it..." This good will come through God's action on the human heart where he "is ever working to awaken love, the divine motive."

He appeals to man through all forms of the wise and wonderful, the true and beautiful, the good and lovable. He excites admiration by the revelations of himself in the material universe...And he is present in all human thought and achievement, in all human excellence and perfection, in all human virtue and loveliness, commending himself to our minds and hearts. Truly to love him...to love the true, the beautiful, and the good as they are revealed in all forms of life around us; and to serve him rightly is...to work with him for the overthrow of all that is evil and the establishment of all that is good.

In Cave's conception of God there is a modification of the rationalist's image of nature's God through an appeal to the idealist's vision of a force active in the human soul. "Manifestations of him are both physical and spiritual," declared Cave. "He reveals himself in the phenomena of the material universe and in the phenomena of the human soul." As an "infinite force acting in accordance with wise laws," God is "the universal Spirit which voices itself in all sounds, reveals itself in all colors, and unfolds itself in all forms--the invisible essence of being which clothes itself in the visible universe." Yet God is also described as "revealed in human consciousness. He is present in the spirit of man as well as in the material world. He lives in the impulses and longings and hopes and aspirations of the human soul no less truly than in the forces of physical nature." The mission of Jesus, though clearly didactic, has at its core the declaration of "the divinity of human nature--thus revealing God in man." As the teacher of this saving truth Jesus is "a representative of humanity...an unfailing source of encouragement and strength, and a prophecy of humanity redeemed and glorified."

![]()

-"not what form of worship he adopts, but what spirit dwells in him"-

For Cave morality constituted the heart of religion. He charged the orthodox with having separated the two and having placed special emphasis on man's duty to God rather than upon his duty to his neighbor. "Of all the pernicious doctrines that have been taught in the sacred name of Christianity," wrote Cave, "it seems to me that this is one of the most pernicious." Speaking of and to the Disciples of Christ with their proclivity for a legalistic restitutionism, Cave clearly delineated the weakness of their program:

We have heard much of "Apostolic Precedent" and the Restoration of the Ancient Order of Things"...What we need is not the restoration of old forms but the restoration of the old spirit--the spirit of sublime unselfishness and self-sacrifice which is born of divine love, and which, revealing itself in methods suited to its circumstances, adapting itself to the needs of the age in which it lives, and becoming all things to all men, abides forever and works out the best results for God and humanity.

Elsewhere Cave insisted on

the identification of religion with morality rather than with formal

religious rites or dogmas as a prerequisite for ecumenism. "On this

moral creed we can stand together," he wrote, "however we may

differ in our theological beliefs. It is a creed of just on word, and that

word is RIGHTEOUSNESS." Cave reminded his congregation that "it

is the pure in heart rather than the sound in faith who shall see

God," and this observation led to the affirmation that anyone living

a life of "unselfish devotion to the interests of humanity" is,

regardless of his knowledge of doctrine, "a Christian and one of

God's anointed." This commitment to deed rather than to creed was the

hallmark of the Non-Sectarian Church.

Cave explained:

We hold that love to God and love to man is the sum of all religion, the only essential thing in Christianity, and the only rightful basis of Christian fellowship and fraternity. We hold that the all-important matter is not what man believes, but what he is; not what form of worship he adopts, but what spirit dwells in him; not what ceremonies he observes but what character he builds. We hold that every one should be true to the voice of God that he hears in the depths of his own soul, urging him to righteousness; and that, being true to that voice, he cannot fail to form a character brave, tender, and true, which man must honor, which woman may trust, and which heaven will approve.

Cave's soteriology reflected his focus on moral conduct as the core of religion. He rejected alike theories of depravity and of atonement. "Man is lost," explained Cave, "in the sense that he is ignorant. He is morally blind..." He mistakes the evil for the good." He is...morally weak." Because of man's ignorance and weakness "he is living in a state of alienation from the divine life, straying from the right, running in the wrong, violating the law of his nature, which is the whole law of God as it relates to him, and bringing upon himself not the wrath of God-not any arbitrary punishment-but the penalty of wrecked being and pain naturally resulting from transgression." Thus Christ's purpose was to save man by "removing his ignorance and weakness and bringing him to respect others as himself, to hate all that is evil, to love all that is true and beautiful and good, and to hold his passions in subjection to a will which is 'the servant of a tender conscience.'"

Consequently Cave's Jesus was primarily the teacher of morality. "He is the one Universal Teacher of all history," said Cave, "and universality declares him to be a Teacher come from God." Yet Jesus' instruction is to be discerned from his life no less than his teachings. "Jesus not only taught that God is an ever-present and universal Father and that all men are brethren, but he exemplified that teaching in his life...And it was living the truth rather than teaching the truth that enthroned him above all others in the heart of mankind and made him the acknowledged leader in human progress and civilization." It was the spirit of Jesus which "ennobled and beautified and glorified his life [and] to which Jesus called men...He called upon men to come unto his spirit; to make their characters like his; to recognize the Fatherhood of God and the Brotherhood of man as he recognized them...to be pure and true and just righteous and loving as he was; and...to give themselves in loving service to humanity as he did."

Cave's ecclesiology reflected the centrality of this dominical message. In a sermon preached shortly after the formation of the new church Cave declared that the church is built on Jesus Christ but that "it cannot be built on Him as a person, for it is impossible to build an abiding society on a person. The world is governed and guided not by persons, but by ideas, and hence the church cannot be built on the person of Christ...Jesus Christ was a representative man. He was an embodiment of eternal truth, and in many passages of Scripture, I find His name standing not for Himself as a person, but for that which He embodied." He objected that the apostolic church actually "fell far short of realizing the conception of Christ and giving the world an embodiment of pure Christianity." Denying "that the church which Jesus came to establish is an organized society of his followers, with an authoritative form of government, a dogmatic creed, and divinely ordained ceremonies." Cave insisted that it is "a divine fellowship, founded on love and governed by love--a fellowship composed of those who...partake of the spirit of Christhood and sonship which he taught and manifested and so become Christs and sons of the living God themselves..."

Cave's universalism most clearly reflected the influence of contemporary religious currents. He had been impressed by Edward Beecher's 1878 defense of the doctrine of universal salvation, and his own doctrineless Christianity rendered all distinctions among religions save those of moral effect meaningless. Denying that Jesus taught the necessity of church or sacraments, Cave insisted that "Jesus taught a universal religion--a religion adapted to all times, all circumstances, and all classes and conditions of men...To make any definite ceremonial observance a part of religion is to rob the religion of universality."

Though his University of Missouri baccalaureate sermon had been reported on the front page of the Post-Dispatch under the headline "They Don't Like It," Cave in the following year was chosen the city's most popular minister in a contest sponsored by the Republic and thereby won a free trip to Europe and the Holy Land. He traveled through the spring and summer of 1892 and returned in September to create another press sensation through his sermon entitled "The Salvation of the World" in which the full scope of his universalism was revealed. Declaring the supreme desire of God to be the salvation of the world and not merely of an elect portion, Cave insisted that saving power is not limited to Jesus but is evidenced in all great religious leaders: Zoroaster, Buddha, Confucius, Socrates, Moses, Elijah, David, Isaiah, and all the prophets. They "brought to men new or fuller revelations of truth, and lifted them Godward in thought and aspiration..." In this sense all were saviors, and they differ from Jesus not in kind but in degree in that Jesus surpassed all. Cave concluded with the observation that Christians are called to be saviors today and in a later sermon reminiscent of transcendental Unitarianism declared that God was in Jesus in greater measure but in much the same way that God is in every person. Consequently for Cave various religions were simply phases of the same religion, and all derived from spiritual intuitions implanted in human nature by God. Ultimately all religious inspiration led to one universal religion and to the one God who is the source of that inspiration. Cave's universalism, like his conception of God, reflects both rationalistic and idealistic influences. His identification of the universal core of religion with moral righteousness common to every religious tradition reflected an abiding impact of Enlightenment rationalism. Yet his description of a god-given core of truth present only in greater measure in major religious leaders but implanted in every human soul linked Cave to philosophical idealism.

![]()

-Liberal in content, the program was conservative in purpose-

Robert Cave's dramatic career in St. Louis during the last decade of the nineteenth century constitutes further evidence for Arthur Schlesinger's thesis of a "critical period in American religion" and more particularly for that phenomenon described by Paul Carter as "the spiritual crisis of the gilded age." Cave clearly believed that the Christianity of his youth and of the major churches, a Christianity which he termed orthodoxy, was no longer either emotionally appealing or intellectually viable. Religious knowledge he held to be evolutionary, and therefore even since the time of Christ "the thoughts of men have widened with the process of the suns,' and [he believed] they will continue to widen." It was to this new perception of religion and to the yearning of modern men and women for a more adequate religious understanding that Cave addressed himself from the pulpit and in print. The considerable, positive response to his ministry suggests that many shared Cave's convictions.

The central thrust of Cave's ministry may therefore be characterized as an effort to breathe new life into an inherited religious tradition. Liberal in content, the program was conservative in purpose. Such an interpretation is supported by the gradual evolution of Cave's theology. In an exchange of letters with J. H. Garrison in 1890 Cave declared that "the views of church fellowship which I entertain have been held by me for about fifteen years" which would suggest that his transition to modernism commenced no later than 1875 when he left the Apostolic Times. By the time Cave came into the public eye in St. Louis the transformation in his theology was essentially complete. Yet during the intervening years one may detect only gradual rather than sudden change. When the arch conservative David Lipscomb visited Hopkinsville in 1877 while Cave was both president of the college and minister of the Christian Church, he could find nothing to complain of save that the brethren stood for prayer. yet in the aftermath of the St. Louis controversy Lipscomb declared that Cave's "defection...does not surprise us." Cave affirmed in 1890 that during these years he had "labored for three of the oldest and most influential congregations in the brotherhood of Disciples without causing any trouble." One can only conclude that Cave's modernism developed imperceptibly and that it provoked little criticism until December, 1889.

Cave as a modernist is particularly interesting because of his southern origins and his ability to combine theological modernism with political and economic conservatism. Cave's proclivity for states' rights and for minimal government, clearly enunciated in his Richmond address, was revealed once more in the aftermath of the First World War when he prepared an address opposing American entry into the League of Nations. In it Cave likened the League to the American union of sovereign states, a union which had been unable to prevent the Civil War, and challenged the constitutional authority of the government to take the people and states into such a compact. Similarly, Cave was no friend of industrial capitalism. He saw economic forces behind the rival constitutional positions of Union and Confederacy, and he lamented the victory of capitalism no less than that of the Union. He complained that the people of his day had set their minds and hearts "on the possession of material riches as the highest good." In a statement opposing Philippine annexation Cave attacked commercialism which, he said, "is marring our homes, perverting our churches, demoralizing our business, corrupting our political life, and imperiling the existence of our republican institutions." The Jeffersonian agrarianism of Cave's youth recurred as populism at the end of the century, and if Ann Douglas is correct in her assessment of the New England clergy the The feminization of American Culture,, there was a clarity and integrity to Cave's assessment of American society which was missing among many of his theological mentors and cohorts of the Northeast.

Among historians of the Disciples of Christ it has long been assumed that evangelical liberalism triumphed in the North while in the South and Southwest conservatism prevailed leading to the schism between Christian Churches and Churches of Christ. Explanations for the sectional division have assumed that theological liberalism grew out of the sympathy for and accommodation to industrial capitalism and social change. Robert Cave poses a serious challenge to such generalizations. A southerner, Cave was unsympathetic to industrial capitalism and yet dramatically challenged the theological tradition of his denomination. Further, while Cave was followed in his exodus from Central Church by a large contingent of southerners, J. H. Garrison, an ardent Unionist, appears to have rallied the Yankees as a faithful remnant contending for the faith once delivered to the saints. Perhaps geographic and economic explanations for theological currents are not as significant as they have sometimes been regarded.

Finally, Cave is important as a creature of the press. Considerable attention has been devoted to the role of the religious press in the last century, and Disciple historians have insisted that after the death of Alexander Campbell in 1866 effective denominational leadership fell into the hands of a group of editors who contended among themselves for denominational dominance. Cave's experience with Disciple editors might well test and elucidate this thesis. Yet one of the most significant and interesting aspects of the Cave affair derives from its relationship to the secular press. It was the St. Louis Republic which created the Cave affair and kept it before a city and regional audience for months. It was the Republic's reports which compelled Garrison to take editorial notice of Cave in the Christian-Evangelist. It was the Post-Dispatch and the Republic which featured the controversial aspects of Cave's baccalaureate address, and it was the national press which featured his Richmond address of 1894 making him overnight both a hero in the South and a villain in the North. Thus Cave was both product and victim of the media. The significance of his deviation from other Disciples of Christ quickly declined in the absence of media attention. When Cave in retirement returned to the Christian Church explicitly declaring that he continued to hold the views espoused in 1889, no one in 1917 found them a bar to fellowship. The Standard Publishing Company whose Christian Standard had condemned Cave's heresy in 1889-90 published his A Manual for Ministers in 1918 and his A Manual for Home Devotions in 1919. His death in 1923 was memorialized by appreciative obituaries in both secular and denominational papers. One can only speculate as to whether there would have been a Cave affair without a St. Louis Republic.

Robert Cave was a novelty in the late nineteenth century St. Louis. Neither his theological liberalism nor his political conservatism set well with the majority in his day. Yet his position was remarkably consistent and enjoyed the enthusiastic support of a small but loyal following. His career adds an interesting dimension to our understanding of Protestantism in the gilded age.

Encounter; Vol. 41, No. 2, Spring, 1980

![]()