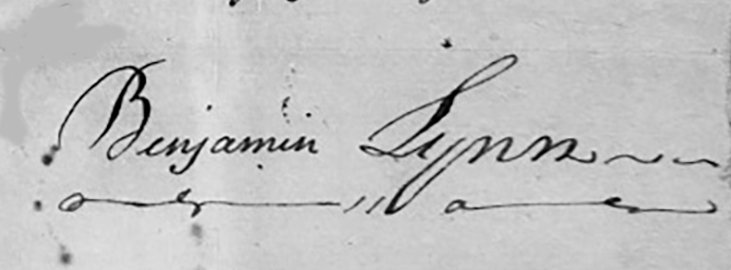

Benjamin Lynn

1750-12.1814

Personal Signature of Benjamin Lynn

![]()

South Fork Baptist Church

Seven persons baptized in Nolin

Creek by Rev. Benjamin Lynn. He

and Rev. James Skaggs founded

South Fork Church ca. 1782.

Organized as Separate Baptist

Church with 13 members, it met at

Phillips' Fort; later moved to

South Fork of Nolin. In the past,

church has assumed philosophy

of United. Separate and Regular

Later split on slavery issue. (Over)

(Other side below)

![]()

Benjamin Lynn--Indian Fighter

The subject of this sketch was born in Chester County, Pennsylvania, in 1750 of Scotch-Irish parents while they were traveling from New Jersey to Maryland. His father was Andrew Linn, Sr., who according to a family history, was brought to America in 1701 ‘as a babe in arms.’ The Linns (after 1792, Benjamin Linn spelled his name “Lynn”) remained in Maryland until about 1767 or 1768 and then moved to southwestern Pennsylvania. About four years later he moved to Kentucky (Chisholm 158).

At seventeen, young Benjamin went into the forest region of Ohio and spent seven years away from his family. He lived among the Shawnee, Delaware, Maumee, and Kickapoo Indians and mastered their languages and customs. He later put this acquired knowledge of the Indians to good use during the long Indian siege of Fort Harrod in 1777. He travelled as far west as the Mississippi River and visited the French. He travelled as far south as Natchez, which gave him a good knowledge of the frontier country. He might have become just as famous as Daniel Boone, had he had a historian for a friend as was John Filson to Boone.

Lynn could fight the Indians or live among them in peace (he killed the first Indian at Harrodsburg during the long siege). He always let the Indians set the mood of interchange between himself and them. It was this sense of adventure which brought him to Kentucky where he lived for over thirty years.

This young frontiersman brought a party of settlers on flatboats to settle near Bardstown, Kentucky, about 1772. John Gilkey and John Ritchie (of sour mash whiskey distillery fame) were among the settlers who came with him. Young Lynn built a fort five miles southeast of Bardstown near Beech Fork Creek. Dr. M. F. Coomes, a Bardstown physician, described the site of Fort Lynn in his paper which he read before the Filson Club of Louisville, Kentucky in 1895 (Coomes 3).

In 1780, when Kentucky was still part of Virginia, Patrick Henry, governor of Virginia, deeded Lynn one thousand acres of land on which his fort had been constructed (Land Records 10:3). In 1774, he helped the settlers at Fort Harrod to strengthen their fortification against the Indians. In, 1777, the fort at Harrodsburg was attacked and besieged for six months. George Rogers Clark was in command at the time. He used Lynn to secure powder and supplies, and to hunt game for the fort. Lynn could slip in and out of the fort under cover of darkness, and the Indians were never the wiser because he spoke their tongue so well and communicated with them.

While under siege, Clark sent Lynn and Samuel Moore to Kaskaskia in Illinois to spy on the British. Lynn and Moore travelled many miles to the west and found the thriving settlement of Kaskaskia. They posed as fur traders and trappers. After a few days, someone discovered their real mission, and they had to flee for their lives. They fled up the Cumberland as far as Nashville and then travelled northeast back to Harrodsburg. Their information would help Clark to break British power in Illinois among the Indians. This exploit may have earned the commission of captain for Lynn. Clark refers to Lynn as Captain Lynn in his official reports after the Kaskaskia mission (Beattie 140-142). In 1780, he went on an expedition to Vincennes and then to Ohio against the Indians. These were his last military activities.

Benjamin Lynn—Pioneer Preacher

Benjamin now turned his interest in another direction—that of a pioneer preacher. He was about thirty years old when he began to think of religion. He allied himself with the Separate Baptists, and made preaching in that group his main occupation. Although unfamiliar with books, he learned to read enough to teach from the Bible. He only learned to read after his marriage to Hannah Sovereigns (Severns according to some documents). Lynn’s marriage to Hannah was on July 9, 1777, during the Indian siege (Clark 6). Records of marriages performed by preacher Lynn are found throughout southern Kentucky until 1802.

It was about this time that Lynn changed from the Baptist to the Christian church. In July, 1802, Lynn occupied a seat in the Green River Association of Baptist Churches. In 1803, Lynn was replaced as minister of the Brush Creek church, the last Baptist church he ever served. Lynn had come under the influence of the Cane Ridge Revival and soon transferred his allegiance from the Baptist to the Christian church (Beattie 154-155). Lynn even travelled to Cane Ridge to be baptized by Barton Stone. One of the earliest ordination certificates known among the Restoration churches was that of Samuel Boyd, signed by Benjamin Lynn and Lewis Bynam. It reads as follows:

We the underwritten do certify that according to a previous appointment on the east fork of Little Barren on Monday after the third Sabbath of July, 1809, Samuel Boyd was publicly set apart by ordination for the work of the Gospel ministry according to the manner of the Christian Church then present at that place--and that as such he is received by the different branches of sd. (sic.) church and in full communion and good standing. Given under our hands the day and year above mentioned, Benjamin Lynn (and) Lewis Bynam (Whitaker 26).

Such documents were common during the early days of the Restoration Movement. A few months after the ordination of Boyd, Lynn moved to Huntsville, Alabama.

John Chisholm, who had married Esther Lynn, Benjamin’s younger daughter, had moved to Huntsville, Alabama, looking for new lands. Lynn followed Chisholm by 1810 and lived the remaining days of his life in the Chisholm household (Shankland 20). In the early part of 1814, Benjamin Lynn established a Christian church in Huntsville. Through the family of John and Esther Chisholm, along with Rachael D’Spain (Esther’s older sister) and her husband, Marshall D’Spain, the church was active in Huntsville for about two years. Benjamin died December 23, 1814, and was buried in the churchyard near the Chisholm home. This brought to an end a most illustrious life of one of Kentucky’s pioneers and unique preachers.

Benjamin Lynn’s Legacy

Though Benjamin Lynn was dead, his influence lives even today. In 1816, the Chisholms moved to Florence, Alabama, in Lauderdale County, bringing the church with them. That same year the D’Spains moved to Waterloo, also in Lauderdale County. They too took the church to Waterloo. The two earliest churches in Northwest Alabama were due, indirectly, to Benjamin Lynn’s labors. The Chisholm work still survives as the Stony Point Church of Christ near Florence, Alabama. It is, possibly, the second oldest congregation still surviving in Alabama.

John and Esther Chisholm’s daughter Dorinda, married B. F. Hall while he was teaching grammar school at the Old Cypress Creek (now Stony Point) meeting house near Florence, Alabama (B. F. Hall 71). John Chisholm corresponded many times with Alexander Campbell and even subscribed to the Millennial Harbinger (Campbell’s Ledger 1830-1836). Chisholm even made provisions in his will to aid Campbell’s work at Bethany College (Lauderdale County Wills 548). It is an interesting sidelight that some of John Chisholm’s relatives were members at the Old Mulkey Meeting House near Tompkinsville, Kentucky. On this list their names appear in the old spelling--“Chism.”

Marshall and Rachael D’Spain had two children who were connected with the Texas movement--Hetty Lynn D’Spain who married Joseph Clark and Lynn D’Spain who became a well-known gospel preacher. In 1835, the entire church at Waterloo, Alabama, moved to Texas, with David Crockett at their head (Colby Hall 55). On the first Sunday in January 1836, the first services ever held in Texas by New Testament Christians (as an organized Church) were conducted near Fort Clark. A few house churches had met from time to time, before this, through the encouragement of William DeFee and others The Lynn legacy was continued in Texas by the D’Spains (now Spain in some places) and the Clarks. Texas Christian University was a result of the work of Addison and Randolph Clark, Lynn’s great-grandsons. The Chisholms and the D’Spains still are influential in the church in Alabama. Many D’Spains (Spain) and their descendants still live in Lauderdale County, Alabama and are faithful members of the church. But the real thanks belong to the founding father of their spiritual line--Benjamin Lynn.

Beattie quotes O. M. Mather of Hodgenville, Kentucky concerning Lynn: “His name is perhaps more securely perpetuated than that of any other person identified with the settlement of the Green River Section of Kentucky” (156). Many places in this region of Kentucky still bear his name. The continuing influence of Benjamin Lynn and his descendants is inestimable in the churches of Christ.

Works Cited

Beattie, George William and Helen Pruitt Beattie. “Pioneer Linns of Kentucky.”

Filson Club Historical Quarterly 20 Jan. 1946: 23.

Campbell, Alexander. Subscribers Ledger Book. (Filed at Bethany College, Bethany, West Virginia).

Chisholm, John. “Letter to John Barbee.” September 16, 1846. (Filed in Filson Club Historical Collection on the Lynn Family).

Clark, Joseph Lynn. Thank God We Made It. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1969.

Coomes, M. F. “Unpublished Paper on Benjamin Lynn.” (Filed in the Filson Club Historical Collection on the Lynn Family).

Hall, B. F. The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin Hall. (Unpublished manuscript in University of Texas Library)

Hall, Colby. Texas Disciples. Fort Worth, TX: Texas Christian University Press, 1953.

Land Records - Jefferson Entries, Book A. p. 146 and Virginia #2029 Grant Book 10, p.30. (Filed in Office of Secretary of State, Capitol Building, Room 148, Frankfort, Kentucky).

Shankland, Albert B. “Benjamin Lynn - Indian Fighter, Hunter, Scout, Preacher.”

Despain Log Chain (Filed in Lynn Biographical File at Huntsville, Alabama).

Whitaker, Wilford W. Despain Log Chain 3 Jan. 1968: 26.

Wills. (Filed in Lauderdale County Court House, Florence, Alabama).by C. W. (Wayne) Kilpatrick, March, 2012

Web Editor's Note: My first recollections of hearing of Benjamin Lynn were in classes on Restoration History, while a student at Heritage Christian University (then, International Bible College). It was back in the late 1980s. One day, upon entering class, our beloved teacher C. Wayne Kilpatrick had us pile into vehicles so he could show us "something." We traveled about six miles from the school, on the Chisholm Hwy., just north of Florence, to a small house on the side of the road. Behind the house was a small cemetery where the remains of the John Chisholm family are buried. It is one of the oldest cemeteries in Alabama. It was the beginning place for your web editor; the beginning of many years and miles of travel to places where Restoration work has been done. Someday, perhaps we can discover more accurately the location of the grave of John Chisholm's father-in-law, Benjamin Lynn. We know it was on some property he owned north of present day Huntsville, perhaps in the vicinity of Meridianville.

![]()

PIONEER LINNS OF KENTUCKY

BENJAMIN LINN(1)--HUNTER, EXPLORER, PREACHER Benjamin Linn', the "hunter preacher," the "Daniel Boone of Southern Kentucky,"(2) is one of a number of men who played noteworthy parts in early Kentucky history but have had no recognition from historians beyond brief mention of a few of the main events of their careers. Unlike Daniel Boone, they had no John Filson to write their biographies early and so preserve a fuller record of their lives. The information in the following pages has been gathered from many different sources, and it will be noted that many important gaps in the story still remain.

According to the best authorities known, Benjamin Linn was born in Chester County, Pennsylvania, in the year 1750, of Scotch-Irish parents en route from New Jersey to Maryland.(3) His father, Andrew Linn, Senior, remained in Maryland some fifteen or seventeen years, and then moved to the valley of the Monongahela River in southwestern Pennsylvania, settling there in 1767 or 1768.(4)

Benjamin accompanied his father and his brothers when they made this change, but he did not join them in acquiring land there. He seems to have been of a different mold, his taste being for hunting rather than for farming. Impelled by the same sort of spirit that drove Daniel Boone and the Long Hunters into the Wilderness, Linn, only seventeen years of age, plunged into the forest regions northwest of the Ohio River and spent seven years away from his people. He lived among the Shawnee, Delaware, Maumee, and Kickapoo Indians for several years, becoming familiar with their languages and customs. He visited the French settlements as far west as the Mississippi River and as far south as Natchez, hunting, trapping, and learning the country as he went.(5)

Neither Benjamin nor his older brother, Colonel William, seemed to feel the bloodthirsty hatred of Indians that characterized such men as Jesse Hughes6 and Lewis Wetzell. He fought them fiercely in war, but lived amicably with them in times of peace. He must have been of the same type as Daniel Boone, Simon Kenton, and Jesse Hughes(6) in his skill and sagacity as a woodsman, but he was different from them in that he could adapt himself to conditions that arose when the strictly pioneer period in Kentucky passed. He could do more than range the forest, and unlike them he was able to keep the lands he acquired.(7)

On one of his trips through Kentucky he stopped to visit the station at Harrodsburg that had been established in 1774, two years before. He remained there for a time, helping the settlers to strengthen their fort in anticipation of Indian attacks, and giving them the benefit of his knowledge and experience.(8) He was one of the thirty men who, in January, 1777, went under the leadership of James Harrod to get the powder that George Rogers Clark had secured from the Council of Virginia and had brought down the Ohio from Fort Pitt, concealing it on the bank of the river until a sufficient force of men was available to transport it safely overland to Harrodsburg. John Todd and a party of ten had attempted to move it but had been overwhelmed by the Indians and had lost three of their number, among them the John Gabriel Jones who had helped Clark to bring the powder from Fort Pitt.(9)

The Council of Virginia was aware of the situation of the pioneers out in Kentucky County, and on March 5, 1777, commissions from Governor Patrick Henry arrived at Harrodsburg for George Rogers Clark as a major of militia, and for Daniel Boone, James Harrod, John Todd, and Benjamin Logan as captains. Men in the settlements were promptly formed into companies, and Simon Kenton, Samuel Moore, Silas Harlan, Thomas Brooks, and Benjamin Linn were appointed scouts to watch the movements of the Indians.(10)

These precautions were taken none too soon. The day after the scouts had been selected, a large band of Indians moving toward Harrodsburg killed William Ray only five miles from, the fort, and early the, next morning cut off a party of men who had gone from the fort to some cabins outside. Benjamin Linn was one of 'this party. In an attempt to decoy the settlers from the fort, the Indians had left some new rifles stacked near one of the cabins where anyone attempting to secure them would be within shooting range. Linn saw the arms, suspected an ambuscade, and dissuaded his companions from approaching them, whereupon the savages, realizing that their stratagem had failed, began firing. In the melee that ensued Linn killed and scalped an Indian, the first one slain in the Siege of Harrodsburg just beginning.(11)

This siege, so familiar to all readers of Kentucky history, was continued with more or less vigor for about six months. On the morning of April 29, 1777, occurred the Tunnel Incident. Francis McConnell and James Ray were surprised by Indians while outside the fort, and McConnell was mortally wounded. He lay behind a log the entire day within sight of his friends in the fort, waving his hand feebly at intervals for help. Ray, a youth of seventeen, managed to reach the stockade unharmed only to find the gates closed and the men inside afraid to open them. He hid behind a stump a few feet from one of the blockhouses of the fort for several hours while his friends tunneled under the wall and dragged him through the opening to safety. This adventure did not unnerve Ray, for he was one of the party that sallied forth that evening to carry the wounded McConnell inside the fort where he died soon after.(12)

According to the account given years afterward by Mrs. Elizabeth Thomas to Dr. Lyman C. Draper when he was collecting materials for what was to be a monumental history of the West, Benjamin Linn was leader of the group that went out to rescue McConnell.(13) Mrs. Thomas, a pioneer woman, was in the fort at the time and had witnessed the occurrence. Considerable evidence, however, exists to show that in this instance her memory was at fault. It is pretty clearly established that Linn was not at Harrodsburg that day.

It was in this same month of April that Benjamin Linn and Samuel Moore went to Kaskaskia under orders of George Rogers Clark, to learn everything possible regarding conditions in the Illinois country. With remarkable vision, Clark had conceived the idea of taking the British military posts north of the Ohio, thereby destroying their power in the Northwest and discomfiting their Indian allies who were making life almost unbearable for the settlers in Kentucky. Before venturing on such an expedition he needed a knowledge of British strength and resources, and it was this knowledge that Linn and Moore were to gain for him.(14)

According to Simon Kenton, Clark originally named four of his five scouts to make this trip but, with the independence and disregard of military authority and discipline so characteristic of frontiersmen, they decided among themselves that two could do the job better than four. They cast lots to see who should go, and the lots fell to Linn and Moore.(15) In his diary Clark makes this entry under the date of April 20, "Ben Linn and Samuel Moore sent express to the Illinois."

The Indians were surrounding Harrodsburg in great numbers at the time, and to venture outside was always hazardous. Captain John Cowan, a man at the fort who kept a diary, gives an idea of the conditions under which the two young woodsmen set out when, under date of April 25, he made this entry: "Linn and Moore set off for Mississippi. Fresh signs of Indians seen at 2 o'clock; they were heard imitating owls, turkies, &c. at 4; centry spied one at 7; centry shot at three at 10 o'clock."

The two men succeeded, nevertheless, in slipping through the Indians watching the fort and set out for their destination by the most direct route, but signs of Indians where they intended to cross the Ohio led them to change their plans. They then worked their way southward to the Cumberland River, where they were fortunate in discovering an unused canoe. Glenn and Laird, two men who arrived at Harrodsburg on June 5, reported seeing Linn and Moore on May 6, embarked on the Cumberland claiming to be on their way to Ozark.(16) The spies had shrewdly refrained from telling their real purpose.

From the mouth of the Cumberland the two men floated down the Ohio to the point nearest to Kaskaskia, hid their canoe, and proceeded overland. At Kaskaskia they represented themselves as hunters from the Mississippi with furs for sale. They even entered the employ" of Rocheblave, the acting British governor, this audacity helping still more to conceal their identity. Unfortunately, the resemblance of their white wool hats to those worn by Kentuckians led certain British adherents, to suspect them of being spies, and their lives soon became unsafe. Linn was also recognized by Indians with whom he had once hunted. The peril of the two men finally became such that n American friend warned them to leave at once. They did so, traveling rapidly without stopping until they were sure that Indians who had been pursuing them had given up the chase. Their consummate woodcraft saved them.

On recrossing the Ohio they found bands of Indians hunting game in that vicinity. They therefore abandoned the Ohio and went south along the ridge that separates the Cumberland and Tennessee rivers, a route that took them into what is now the state of Tennessee, as far as Nashville. With infinite caution they then made their way northward again and, slipping through the still besieging savages, entered Harrodsburg on June 22.(17) Cowan's diary contains the entry for that same day: "Indians killed and beheaded Barney Stagner at the upper end of the town." Stagner had rashly ventured out from the fort.

What Linn and his companion underwent while on this mission can only be imagined, but the information they brought back to Clark was definite and of inestimable value to him in his planning of the Illinois campaign. From them he learned that although the British at Kaskaskia were not apprehensive of any attack by Kentuckians, their fort was well supplied with fighting material, the militia were well trained, and the minds of the French inhabitants of the region were carefully and persistently filled with ideas intended to inflame them against Americans. He learned also that the Indians were allied generally with the British, and were constantly being incited by means of gifts to make war upon the settlers. There were, however, some persons in the region who were well disposed toward the American cause.(18)

Benjamin Linn's own account of his Kaskaskia trip comes to us through two different persons—Andrew Linn, of Cookstown, Pennsylvania, a nephew, and John Chisholm, a son-in-law. Andrew, when a twelve-year-old boy, heard his uncle tell the story at Redstone in 1778, less than a year after the trip was made. Sixty-seven years later, he repeated the tale to Dr. Draper, and it is this account that we have. John Chisholm heard the story, probably more than once, but considerably later when he was a mature man. As might be expected, he gives more details than Andrew of Cookstown gave.(19)

There is nothing in these accounts to suggest that either Linn or Moore had any idea of the great importance of the trip they had taken or of what they had learned at Kaskaskia. The task had called for intelligence, skill, discretion, and physical endurance of the highest order, and it probably was the main undertaking of their lives, little though they ever realized it. They gave only the details of their journey, and made no comments. This was to be expected. Clark says that he took no one into his confidence when he sent them, and it is only in the letters of Clark and Jefferson and in the Treaty of Paris that one gains insight into the Illinois Campaign, the preliminary to which was the spy expedition of Linn and Moore. The most significant thing about the two accounts from a historical standpoint is the information in them concerning assistance rendered him and his companion while they were in Kaskaskia. By combining the two stories to some extent, one gains the following:

An American, a friend of Linn who had known him when he was living among the Indians, now living in Kaskaskia and connected with the Indian trade, met the two spies secretly on their arrival, advised them where to camp, ana assisted in the sale of their beaver skins. He warned them not to be seen with him. Later he visited them at night, brought them supplies, and informed them that they were suspected of being spies, and that Indians who had known Linn in years past were holding a council on his base. The American attended the council, learned its decision, which was unfavorable, and reported it to the spies early the next morning. He told them that the inhabitants of Kaskaskia would be at Mass during the earlier part of that day, and business would then be suspended. The Indians would not enter the town until the shops were open', and he urged Lima and Moore to take advantage of this opportunity to make their escape, as they would be killed ff caught. He directed them to his own canoe, in which they immediately crossed the river and set off on a run, traveling three days and nights at such a speed that the Indians who followed them gave up the chase.

The name of the friend Who rendered this service is not given, but the narrative supplies a link to a chain of evidence presented by Clarence W. Alvord in his introduction to the volume containing Kaskaskia records that had been collected, evidence that points strongly to a Kaskaskia merchant. Alvord discusses the possibility that the Illinois Campaign had been preceded by communications of some sort between Thomas Bentley, a British trader-merchant of Kaskaskia, and George Rogers Clark. The records show conclusively that Bentley had been willing to do business with anyone who promised profit. He was decidedly a double-dealer, and the idea of the spying trip very possibly developed from information that got to Clark through him. He had a business agent named Daniel Murray, one of the few Americans living in Kaskaskia. Murray wrote to Bentley at this very time:

"As for the hunters you write of there is three of them, one of which was here before, his name is Benj. Lynn but they bring no news that I can here[sic] of worth your hearing."(20)

One wonders whether such marked friendship and helpfulness as Linn's unnamed American showed was wholly personal in its nature, or whether it was one of the "traces of affection in some of the inhabitants" toward the American cause that Clark says the spies reported to him. One also wonders how the two spies making their hurried trip to Kaskaskia could have had a supply of beaver skins fit for market. Were these skins, designed to complete their disguise as trappers, provided by the third hunter who according to Murray entered Kaskaskia with them? And why did not this third man accompany Linn and Moore in their flight?

Since Murray's letter indicates that he recognized Linn as having been in Kaskaskia before, he must have known him during his sojourn with the Indians, and since it also shows that Murray had conversed with the spies, could he not have been the friend referred to in Linn's narrative? May he not have arranged with some local hunter to share some of his skins with the Kentuckians, for a time? Murray was associated with Bentley in commercial enterprises, but may he not, as an American, have wished to bring the Americans to Illinois? May not his colorless letter to Bentley have been made so purposely, in order that it might pass any British censor and yet be illuminating to the recipient? It was not long after this that Bentley was called before a British Court of Inquiry to answer to the charge that he had been aiding Americans in various ways. It is know that his boats met Benjamin's brother William below the junction of the Ohio and the Mississippi when William was bringing powder up from New Orleans, and supplied him with goodly amounts of food and ammunition. Bentley denied any such activities, but they are proved by records discovered comparatively recently.(21)

Before Linn's return from Kaskaskia, Clark referred to him in his diary without giving him any military title. But beginning with July 5, in the Court Martial Book of Kentucky County, he records the name of Lieutenant Linn. This suggests that Linn was given official rank after his successful mission.

On July 9, 1777, Clark makes this brief but interesting entry in his diary: "Lieutenant Linn married. Great merriment." The fact that the inhabitants of Harrodsburg, shut up iu a fort amid the horrors of a prolonged Indian siege, could relax sufficiently to indulge in wedding festivities illustrates one of the eternal peculiarities of human nature. Linn married Hannah Sovereigns, member of a Welsh family that had gone through the rigors of the French and Indian War on the Potomac along with the Linns. Her father had been killed then, and Hannah, her mother, and her brothers and sisters had been taken captive by the Indians, carried into the Ohio country, and held there until rescued by the expedition led by Colonel Henry Bouquet in 1764.(22) Hannah was a pioneer in her own right. She came early to Kentucky with her brothers, and as an independent farmer occupied land at the Yellow Banks above the mouth of Green River a year or two prior to her marriage.(23)

The so-called Turnip-patch Affair is described by Linn in the accounts he gave Andrew Linn of Cookstown. It occurred August 5, 1777, the last recorded incident in the Siege of Harrodsburg before the Indians left. While seated at the door of his cabin mending his moccasins, he noted the nervousness of some cattle grazing a short distance away. Linn and those with him knew instantly what it meant. Indians were lurking in the bushes beyond. The men in the cabin left it by another door and crept up behind the savages, killing three and sending the others off in flight. They dropped guns, tomahawks, and packs as they ran, and at an auction of this plunder held soon after, Benjamin purchased a tomahawk.(24)

The next appearance of Benjamin was in the winter of 1777, when he returned to the home of his father and brothers on the Monongahela bearing a letter from Colonel John Bow: man, Kentucky County Lieutenant, to General Hand, the Commanding Officer at Fort Pitt (now Pittsburgh). The letter described conditions among

"the poor Kentucky people who have these twelve months past been confined to three forts on which the Indians have made several fruitless attempts. They have left us almost without horses sufficient to supply the stations, and we are obliged to get all our provisions out of the woods. Our corn the Indians have burned . . . at this time we have not more than two months bread-near 200 women and children . . . many of these families are left desolate widows with small children destitute of necessary clothing."

The next statement, "Necessity has obliged many of our young men to go to Monongahela for clothing," may explain Linn's making such a trip at this time, leaving his wife behind at Harrodsburg. He was never deaf to appeals for help. Accompanying Linn was John Bailey, who served later as an officer under Clark in the Illinois Regiment.(25) He appears again in connection with Linn, but in a very different capacity, as will be seen.

Clark had left Harrodsburg in the preceding October, after the long siege had ended, for Virginia to secure authority from Governor Patrick Henry and tile Virginia Council to recruit men for the expedition to the Illinois country. He went by the Wilderness Road, but he returned by way of Redstone Fort on the Monongahela, and while there began recruiting in that vicinity. Referring to this part of his military activities in his "Memoir," he says, "I appointed Captain William Harrod and many officers to the recruiting service"; and in his diary under date of February 8, he says, "Appointed Samuel Moore Lieutenant under Captain Harrod, also Benjamin Linn to raise a company."

It was probably about this time that Clark issued a commission to Linn as Captain. The Court Martial Book Of the Illinois Regiment in 1779 refers to him as Captain Lynn. John Chisholm, in writing to Dr. Draper about Linn, invariably refers to him as Captain Lynn.

Clark discontinued somewhat suddenly the mustering of men in the Monongahela Valley, where Linn must have been at the time, on receiving what later proved to be a misleading report concerning the progress of the recruiting on the Holston River and the region about Winchester. Clark was near Redstone at the time, and his letter to General Hand at Fort Pitt announcing this change of plan and General Hand's reply to it were carried by a messenger designated as "Mr. Linn." This was probably Benjamin, although William was then arranging to move his family from Redstone to the Falls of the" Ohio, at the Louisville of today, under the protection of the Illinois Expedition, and he may have been the bearer.(26)

For some unknown reason Benjamin did not accompany Clark to the Illinois country, and because of this fact his claim, in 1784, for an allotment of land in the Clark Grant was. disallowed, notwithstanding the services he had rendered in preparing the way for the expedition.(27) His brother William did go, as we know.

Dr. Draper attempts to explain Benjamin's absence by saying that he was "probably needed to remain as a hunter for the supply of Harrodsburg.(28) This suggestion finds support in a deposition given in a land case by Linn himself in which he says that in the fall of 1778 he traveled from Pottinger's Creek to the head of the same, and that in the spring of 1779 he traveled up said creek.(29) This deposition contains all the definite' information we have concerning Linn's whereabouts while the Illinois Campaign was in progress. Why he was making these trips along Pottinger's Creek is unknown. He may have been hunting for game. The creek was some thirty or thirty-five miles from Harrodsburg, and game in the vicinity of the fort was practically exhausted.

John Chisholm says that Benjamin was at the Falls of the Ohio when the Clark expedition reached that point on its trip down the river from Fort Pitt, that Clark there assigned him to a command of seventeen men to assist in guarding Harrodsburg during the absence of Clark's forces, and it was from this command that Linn and Moore were detailed for the spying trip.(30) Chisholm is clearly in error concerning the spy trip, for it had been made in the previous year, but it is hard to ignore his definite statement regarding the guard of seventeen men under Linn who were designated as protectors of Harrodsburg. -It is more than probable that Benjamin returned from Redstone to the Falls of the Ohio with the Clark force, and it is also entirely possible that he was sent to Harrodsburg as an officer of the militia garrison left for its defense. As Draper suggests, he doubtless hunted to help keep up the fort's larder.

We next hear from Benjamin in June, 1779, when, according to Dr. Draper, "Captain Ben Linn went to Vincennes with a small company of fifteen men."(31) It is well known that Clark's plans for the occupation of the Northwest had the British post at Detroit as its objective, since it was from there that the Indians were being incited to harry the settlers in Kentucky. Clark had won a spectacular victory at Vincennes, and had confidence in his ability to carry his plans to completion provided he could have enough men. Before he ever started on his undertaking to conquer the Northwest, he had had assurance from the Virginia authorities of reinforcements to the number of five hundred men, and John Bowman, the Kentucky County Lieutenant, had promised three hundred men from Kentucky.(32)

With these men in addition to those already with him, the expedition to Detroit could have succeeded, but when Clark returned to Vincennes from Kaskaskia he found only one hundred and fifty of the five hundred expected from Virginia, while of the three hundred promised from Kentucky only thirty had arrived. Linn's band of fifteen must have been part of this number. The plan to capture Detroit was promptly abandoned since, as Clark says in his" "Memoir," "The loss of the expedition was too obvious to hesitate about it. ''(33)

Clarks refers to the men from Kentucky as being under the command of Captain McGary, but Dr. Draper's note, the authority for which however is not cited, suggests that McGary and Linn had fifteen men each. The Court Martial Book of the Illinois Regiment shows that Captain Linn was in Vincennes in July, 1779, and at one time at least was decidedly in evidence. There was a personal encounter between him and a Frenchman in which the-Kentuckian was clearly coming out best when he was called off by a superior officer. In this fight such rules as govern fistic combats in our day were lacking. According to the creed of the Kentucky frontiersmen, kicking, biting, hair-pulling, eye-gouging, and throttling were all allowable- anything to win. During the encounter the Frenchman exclaimed in disgust, "I won't fight with nobody but a man. You bite like a horse." The record says that Benjamin released his antagonist instantly upon being so ordered, but unfortunately there is nothing to show what had roused his Scotch-Irish blood to such an extent in the first place?(34)

After returning from Vincennes Benjamin accompanied Clark in the successful campaign of 1780 against the Indian towns of Old Chillicothe and Piqua on the Big Miami River in what is now Ohio, a campaign in which his brother, Colonel William Linn, commanded a regiment?' His service in this expedition is the last military activity on Benjamin's part of which we have any record.

At this time his home was near the present Louisville,(36) a few miles from Linn's Station where Colonel William lived. The Virginia Land Commission had allotted Benjamin's wife, Hannah, fourteen hundred acres on the South Fork of Beargrass Creek in lieu of the lands at the Yellow Banks on which she had made improvements in 1775, as already described. The Yellow Banks tract had been found to be covered by an earlier military warrant(37)

Benjamin himself made two appearances before the Court of Land Commissioners, the first on October 31, 1779, at Harrodsburg, when he submitted his own claim .to fourteen hundred acres of land north of Green River.(38) This tract was on or near the site of what is now Hodgenville, and was the first on which improvements had been made in that locality.(39) The improvements, which he said were made prior to January 1, 1778, were probably very crude-perhaps no more than a girdling of trees so that they would die and corn could be planted among them, and possibly some rude living habitation- the sort of procedure known as "tomahawking a claim." Whether the improvements were made before or after the Siege of Harrodsburg is not known. He never took title to the land, although his claim was approved by the Commission.

His second appearance before the Land Commission was on February 12, 1780, when it was sitting at Louisville. Here he represented the heirs of Eli Gerrard, or Garrard, who had" been killed in 1777 during the Siege of Harrodsburg.(40)

Up to this time Benjamin's life had been that of a hunter, trapper, explorer, scout, and Indian fighter. At the age of thirty he entered upon a new and entirely different career, that of a pioneer preacher. Although unfamiliar with books, learning to read only after his marriage,(41) he allied himself with the Separate Baptists and made preaching and pastoral work in that denomination his main occupation for the next twenty-two years, ranking, through sheer native force of character and sincerity of purpose, with the foremost of his associates. However, during all the years be devoted to preaching his love of the wilderness persisted, and he spent a portion of his time hunting and exploring. Thus it is that he has passed into Kentucky history as the "'hunter preacher."(42)

The fact that a rough-and-ready frontiersman could develop into an acceptable preacher of the Gospel seems remarkable even when we remember that his audiences could not have been over critical, and yet who can know how long he had been engaging in serious thought. The Scotch-Irish were a deeply religious people, and the life of that period, with its familiarity with suffering-and death, could hardly fail to leave its impress upon him. We know that some of his associates were men of simple and yet deep religious feeling, men, for example, like Henry Wilson or John LaRue. The preachers of his day were men of unusual power, men who wrought wonderfully upon the minds and hearts of their listeners.

The Baptists had established themselves in Redstone, Pennsylvania, as early as 1766 or 1768, and the Linns, who arrived there at about the same time, became prominent supporters.(43) But Benjamin had left almost immediately for his long sojourn in the Wilderness, and he could have been but little affected by the preaching of that locality. Also, during his early years in Kentucky, preachers were infrequent visitors. Who, then, was it that had converted him?

In Virginia, forces that were soon to exert great influence in Kentucky had long been active. Virginia was a stronghold of the Established Church of England, and other denominations there were barely tolerated, were in fact subjected frequently to oppression ff not persecution. But they had not been suppressed. Even before the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, the Separate Baptists, with their intense opposition to State control in matters of religion, had profited by the prevailing spirit of revolt among many of the colonists and had made a phenomenal growth throughout Virginia, a growth which spread over into the Carolinas. About 1780, many Separate Baptists were among the immigrants making their way into Kentucky from these colonies, and with them came some of their most enthusiastic and influential preachers.(44) Although we have no direct knowledge, we can readily infer from what we know of his life that Benjamin Linn came into contact with some of them and that they had much to do with shaping his beliefs and his later career.

Among these preachers were William Marshall and James Skaggs, Marshall having been a recognized leader of the Separate Baptists in Virginia.(45) Squire Boone, a brother of Daniel Boone, was a Regular Baptist preacher, the Regulars differing in certain details of belief from the Separates. He and Linn had both been in the fort at Harrodsburg during the dreadful siege there. In 1778 and 1779 Boone had been selecting lands for John and James LaRue in what later was called the Nolin Valley,(46) and as Linn was hunting there at the time,(47) the two men probably met frequently.

John Bailey who, we remember, accompanied Linn on his trip from Harrodsburg to the Monongahela in 1777, became a Separate Baptist preacher in time. The two men doubtless had had abundant opportunities for serious conversation on that long journey, and it is not hard to believe that the urge toward a more spiritual life was even then making itself felt in them.

We know nothing concerning Linn's formal admission to the ministry, but he began preaching before the end of the Revolution, and Skaggs was associated with him in his earliest work. J.H. Spencer, in his History of Kentucky Baptists, says that at the end of 1780 there were three ordained Separate Baptist preachers in Kentucky-James Skaggs, William Marshall, and Benjamin Linn. John Bailey did not begin his preaching until after the Revolution closed.(48)

The Virginia Land Law of 1779 stimulated speculation in Kentucky lands, and men familiar with the country, men such as Squire Boone and John Severns, Benjamin Lima's brother-in-law, were employed at times to select desirable tracts on which entries might be made. Benjamin accompanied Severns on some of his trips.(49) Early in 1780, in company with John LaRue, John Garrard, then a licentiate in the Baptist church, John Severns and others, Benjamin went on a hunting and exploring trip to the region where Hodgenville now stands and where Linn had tomahawked a claim earlier, as we have seen. They selected a knoll as a camping site, and began the search for a location suitable for a settlement, where Linn was doubtless slated to undertake pastoral work.(50)

The explorers, ten in number, arranged to separate during the day and return at night to the camp on the knoll. One night Linn did not return, and a member of the party on reaching the camp exclaimed, "This is the knoll, but no Linn.'" From this or some similar remark was derived the name Nolin given to the creek that flowed by the camp and into Green River, a name by which it is known today.(51)

This trivial incident gave rise to a persistent legend. The commonest version of it is to the effect that Linn was lost, and tales have been written of the anxieties attending the search for him. His own account as repeated to his son-in-law, John Chisholm, is very different and much more consistent. Chisholm says, in substance, that on the first day out Linn noted a fresh Indian trail, and true to his instincts as a scout and woodsman, he followed it to learn the destination of the savages, going so far that he could not get back to his companions that night. No specific mention is made by Chisholm of a searching party, although he does speak of the members of the company as returning to camp one by one the second night, saying, "No Linn yet?" until Linn finally appeared.(52)

That anyone who had spent years in the wilds and was as famed as Linn was for woodcraft could have been lost on this occasion is most unlikely, especially when we remember that probably no white man was then more familiar with the country between Green and Salt" rivers than he was. He undoubtedly had covered that part of Kentucky during his years of hunting and trapping in the wilderness before Kentucky was ever settled. Family tradition has it that his appearance at Harrodsburg, in 1776, was due to his knowledge that in that region there were "many camp sites with convenient water."(53) His work as a scout in the spring of 1777 must also have enlarged his knowledge of that region. According to Chisholm, Linn and Moore traveled to the Beech Fork of Salt River, crossing it near the mouth of the Rolling Fork, through the region afterwards called Nolin," when they made their trip to Kaskaskia.

To carry the matter farther, the land case deposition to which reference has already been made shows that Linn traveled the length of Pottinger's Creek in the fall of 1778 and again in the spring of 1779. Each time he must have covered considerably more territory than he mentioned, since Pottinger's Creek is only about eight miles long. In another deposition, John Severns states that he, with Linn and others, were hunting in November, 1779, and made a camp on the south side of Green River two miles below the mouth of Little Barren River, in this same region. Samuel Haycraft also deposes 'that in the fall of 1780 he, with John Severns and others, explored the Barrens south of Nolin, a region through which Severns and his brother-in-law, Benjamin Linn, had hunted some time before.(54) All this shows how familiar Linn must have been with that part of the country, and satisfies one that his comrades could hardly have thought him lost. They might have feared that he had been captured or killed, and they might have gone to look for him for that reason. Local tradition maintains that a party did go in search of him, and that a place where he had camped was found on the bank of a stream which they named Linn Camp Creek.(55)

According to the tradition, the expedition which gave Nolin Creek its name was undertaken in 1781. Evidence exists, however, to show that it was at least one year earlier. If the story relating to the searching party is correct, Linn Camp and Nolin must have received their names at the same time. John Severns deposes on one occasion that in November, 1779, the stream Linn Camp had no name, while on June 17, 1780, Robert Todd, when entering a piece of land described it as "on the barrens of Green River on Nolin Creek." The expedition which gave these names must therefore have been between November, 1779, and June 17, 1780.(56)

Linn lived for some time at Phillips' Fort, which was built in 1780 or 1781 near the knoll where he and his companions camped when exploring the region. In the summer of 1782, with the co-operation of James Skaggs, he organized a church there known as the South Fork Church. This was the fourth Baptist church founded in Kentucky, and the first to be formed by the Separate Baptists. According to tradition, it was "'constituted" early in the summer under the boughs of a great oak tree and meetings were held there throughout the rest of the season, "experience meetings" being regular features.(57)

Shortly after Linn began his work seven persons were approved for baptism. The times were most troublous. Savages were lurking in the surrounding forests, and only a few weeks before Elder John Garrard had disappeared from an adjoining neighborhood, presumably killed by Indians. The candidates [or baptism are said to have been accompanied to Nolin River by armed settlers, where they were immersed by Elder Linn; and if the traditional accounts of this church are correct, these were the first persons baptized in Kentucky. The accounts have been questioned in recent years.(58)

In 1785, Linn acquired a patent to one thousand acres of land on the south side of the Beech Fork of Salt River, six miles southwest of Bardstown, a tract to which he had previously purchased a pre-emption right from his brother-in-law, Gower Severns. When he obtained the patent the land was in Jefferson County, but that year the portion of Jefferson County in which the land lay was set aside as Nelson County.(59) He established a home on this land the same year and organized Pottinger's Creek Church, becoming its first pastor. It was in this church that he had his own membership.(60)

Linn and Skaggs also established a church known as Level Wood about fourteen miles southeast of where Hodgenville now stands. Linn was pastor of South Fork, Level Wood, and Pottinger's Creek churches as long as he remained in Nelson County. Spencer, our Baptist church historian, considers it probable that Linn also organized the church founded in 1790 on the west fork of Cox's Creek.(61)

In 1785 some break in his physical powers seems to have interfered with Linn's activities, for in November of that year the Nelson County Court entered an order excusing him from his share of public road work, "while he remains in his present infirm state." The hardships of pioneer life, the care of widely scattered churches, and the perils to health attending the clearing of new lands may have undermined what must have been an exceptionally vigorous constitution.

Some time after 1790, Linn moved from Nelson to what later became Green County, and before leaving he disposed of portions of his thousand-acre pre-emption tract, through three different deeds. The last of this tract was transferred in 1794, after he had changed his residence.(62)

On April 14, 1789, the Nelson County Court had ordered "that Benjamin Linn have license to celebrate matrimony according to law," and numerous marriages performed by him are recorded in Bardstown between May, 1789, and June, 1792.(63) One hundred and two marriages performed by him are recorded in Green County between the years 1.793 and 1802. From these dates one may infer that his move from Nelson to Green County occurred in 1792.

Linn's moving to Green County resulted in a reunion there of the surviving members of his family. James, his only living brother, had come from Pennsylvania(64) and had made his home near Greensburg on Meadow Creek.(65) With James had come the old father, Andrew, Senior, who lived in Kentucky with his children from then on until his death in 1800. A sister, Nancy, had married William Graham in South Carolina, and had moved from there to Green County, settling on Brush Creek. Their son, Johnson Graham, became a Baptist preacher well known in Kentucky.(66)

The reports of marriages performed, by Linn from 1800 to 1802 are in lists given by years only, the details supplied m the earlier reports being omitted. This may have been due to his preoccupation with the Great Revival which occurred during these years, and which necessitated an almost continuous absence from home. In 1801, he assisted in the organization of Liberty Church on the West Fork of Brush Creek, a church which was a product of the Revival.(67)

During this Great Revival Linn came under the influence of that gifted leader, Barton W. Stone, and as a result he transferred his allegiance from the Baptists to the Christians, as the followers of Stone called themselves. He relinquished the pastorate of the Brush Creek Church at the same time, and his successor was appointed in 1808, about the time that Barton W. Stone withdrew from the Presbyterian Synod.(68) Since Benjamin Linn occupied a seat in the Green River Association of Baptist Churches in July, 1802, at a meeting in what is now Monroe County,(69) the change from the Baptists to the Christians must have been made some time later.

The shift in Benjamin's religious beliefs and affiliations seems natural enough when one remembers the various forms that the Baptist faith assumed in his day. The Regulars were in agreement with the Separates in regard to baptism, but in certain other matters of doctrine they were Calvinists while the Separates were Arminians. Long continued efforts in Virginia to bring about a union of the two bodies had resulted finally in the adoption of the Philadelphia Confession of Faith, a Calvinistic document but with provisions against a too rigid construction. Later, in 1787, the two Virginia bodies united and agreed to drop the terms Separate and Regular, but the union was not accomplished in Kentucky until 1801 during the Great Revival. Many of the Separate Baptists did not enter the united organization, and of those who did enter, many left later to follow the leadership of Stone.(70)

It is easy to understand how a man like Benjamin Linn, ignorant of theology and church doctrine, untrained in logic, and unaccustomed to critical thinking, would be bewildered by the arguments on the dogmas of Calvinism. The Bible was probably the only book he had ever read extensively, and his study of it must have been of the most simple type. His religion must have been more of the heart than of the mind. When Stone renounced Calvinism and withdrew from the Presbyterian Synod, he urged his followers to cast away their formularies and creeds and take the Bible only for their guide, to abandon other denominational names and call themselves simply Christians. Men of naive faith like Linn and his associates must have felt that such a church would be more like their Separate Baptist Church of earlier days than was the new United Baptist Church with its nearness to Calvinism.

Where Linn lived and worked immediately after joining the Christians is not known, but the lack of any record of marriages performed by him in Green County after 1802 suggests that lie may have left that county about that time. Andrew Linn, of Cookstown, speaks of hearing from him in 1805, and says he was living then in the Green River region, of which, however, Green County was only a part.(71) He moved to Madison County, Alabama, in 1810, making his home there with his second daughter, Esther, and her husband, John Chisholm. Chisholm had lived in northern Tennessee prior to this,(72) and it is entirely possible that Linn left Kentucky to go to him and his wife, accompanying them when they moved to Alabama. He organized a Christian Church near Huntsville, and it was in the churchyard there that he was buried in December, 1814, in the sixty-fifth year of his age. His wife had died in the preceding May.(73)

Spencer says that before going to Alabama, Benjamin Linn revisited the churches he had served in Nelson and what later became LaRue counties, and was deeply mortified when, owing to the change in his religious affiliations, he was coldly received by people who formerly had loved him. This loss of regard must have lasted but a comparatively short time, for even though he had left their ranks his name was and still is associated with many of the Baptist institutions of that locality, a fact that would seem to furnish proof of the admiration and respect felt for him. Nolin Church, Nolin Association, and Lynn Association are all Baptist organizations. Lynnland Institute was a Baptist school maintained for many years in Hardin County. The buildings bf this school later housed the Kentucky Baptist Orphans" Home at Lynnland Station on the Louisville and Nashville Railroad. The name Linn, or Lynn, is preserved in the geography of Kentucky in Nolin River and Lynn, Camp Creek.(74) In Hodgenville there is a Lynn Hotel, the second of the name to be established there, and there is also a Lynn Mill.(75) In the light of all these uses of his name, the tribute of O. M. Mather, of Hodgenville, seems well deserved. He says: "His [Benjamin Linn's] name is perhaps more securely perpetuated than that of any other person identified with the settlement of the Green River section of Kentucky."(76)

One cannot help wondering how much of the respect shown to his memory was due to the veneration felt for an old spiritual leader and guide, and how much resulted from the appeal the hunter-woodsman type of man that Benjamin was made to the imaginations of the people of southwestern Kentucky. Much of the romance that attaches to the Long Hunters, those shadowy characters whose very existence is frequently known only by inscriptions they left on trees and rocks, must also have attached to him. The years during which those men ranged the Wilderness, years so dim and hazy in Kentucky history, were the years in which the knowledge was being gained that made it possible for pioneers to enter the land later.

Mr. Mather also says that early in 1843, numerous citizens of the southeastern part of Hardin County petitioned the legislature of Kentucky for the establishment of a new county which should be called Lynn, with Hodgenville as its county seat. The act creating the county was approved,' but owing to the fact that John LaRue Helm later governor was then influential in Kentucky State politics, the name Lynn was rejected and the new county was named LaRue, partly in recognition of the many LaRues who were living or had lived there, but particularly in honor of the fine old pioneer, John LaRue, who was the governor's grandfather.(77)

Mr. Spencer calls Benjamin Linn "The famous Benjamin Lynn, the Daniel Boone of the Kentucky Baptists." Others have called him "The Daniel Boone of Southern Kentucky." As stated earlier in this sketch, it is greatly to be regretted that he had no early biographer. Our knowledge of his personal appearance is limited to brief statements made by his nephew, Andrew Linn, of Cookstown, and his granddaughter, Miss Chisholm. Both agree that he was a man of only ordinary size, "light made," as Andrew says, and slender, about five feet ten inches tall, and blue-eyed, according to Miss Chisholm. Andrew saw his uncle when Benjamin was twenty-eight, and describes him as a man of fair complexion. Miss Chisholm writing either from her recollection of him in his old age or from a description given by her parents, speaks of him as a dark-skinned man.(78)

Fortunately, our means of estimating his character seem less meager than the hints suggesting his personal appearance. Rugged strength, honesty, sincerity, and the desire to aid and uplift manifest themselves continually throughout the story of his life. His marriage into such a family as that of the Sovereigns (Severns) is significant. He and his brother-in-law, John Severns, had many traits in common. Both had the love of the open-air life, both were skilled woodsmen; both were able to live among and hold the respect of both Indians and white men. Their moral and religious qualities were similar.

John Chisholm says, in replying to Dr. Draper's letter of inquiry: "I feel under great obligation to you for the interest you have taken to do justice to the services of one of the best men of his day and time.(79)

The Reverend S. H. Ford, in the "Christian Repository" in 1856, speaking of him, says, "To the scattered huntsmen he was the messenger of peace. In Phillips' Fort, at No-lin, all along the stations on Green River, wherever a settlement was made, Linn was found an early visitor, swimming rivers, passing through the most perilous dangers, on his hands and knees at midnight crawling through or near the Indian encampments. He counted not his life dear unto him, that he might preach the unsearchable riches of Christ, instruct and confirm and comfort the suffering forefathers of Kentucky."(80)

FOOTNOTES

(1)Early Pennsylvania and Kentucky records show Linn as the surname of Benjamin's family, but later records show the form Lynn. Marriages which he performed in Nelson County, Kentucky, prior to 1792, are recorded as by Linn, but those he performed during the next ten years, in Green County, are by Lynn. J. H. Spencer, in his History of Kentucky Baptists, always spells the name Lynn. As will be seen in the present work, descendants of Colonel William, Benjamin s brother, retained the earlier form, notably in the case of U. S. Senator Lewis Fields Linn, of Missouri. Descendants of Benjamin s brother, Colonel Andrew, Jr., in Pennsylvania, seem to have adopted the form Lynn, as do the descendants of his brother, James.

(2)Appleton, Cyclopedia of American Biography, IV, 66.

(3) John Chisholm son-in-law of Benjamin Linn in a letter to John Barbee, September 16, 1846, gives 1750 as the year of Benjamin's birth (D.M. 31J105), although Benjamin's nephew, Andrew Linn of Cookstown (now Fayette City), Pennsylvania, in an interview with Draper places the birth in 1788 (D.M. 37J22-41). The statement by Chisholm is probably the more nearly correct, since he married Benjamin's daughter, Esther, eighteen years before Linn s death and the two families lived together for several years. He would naturally have known Linn's age. Furthermore, George Rogers Clark, in his Memoir (Illinois Historical Collections, VIII, 218) describes Ben Linn and Sam Moore, whom he sent as spies to Kaskaskia, as "two young hunters." If Andrew of Cookstown were correct, Linn would have been thirty-nine years old when he went on that famous undertaking, an age that is hardly young. W. H. Lynn, in a letter cited in n. 5, supports Chisholm in regard to Benjamin's age.

(4)Eliza B. Lynn, Genealogy of Colonel Andrew Lynn, ]r., part I, p. 5, et seq.

(5)Draper interview with Andrew of Cookstown (see n. 3); John Chisholm letter, supra; W. H. Lynn to Helen Pruitt Beattie, August 11, 1917, quoting his father, Andrew, son of James Lynn. James was apparently a half-brother of Benjamin.

(6)"Life of Jesse Hughes," in L. V. McWhorter's The Border Settlers of Northwestern Virginia.

(7)A Virginia patent was issued to him, June 1, 1785, for one thousand acres on the south side of Beech Fork, Jefferson County, Kentucky. (Virginia Grants, Kentucky Land Office, Book X, 30.) This land later became part of Nelson County.

(8)Andrew Linn, interview; letter John Chisholm; letter W. H. Lynn.

(9)Collins, History of Kentucky, II, 466.

(10)Simon Kenton to Cen. Robert Pogue, August 16, 1821. D.M. 15CC161.

(11)Ibid; Andrew Linn interview.

(12)Draper version of the Tunnel Incident. D.M. 4B124-125.

(13)Robert B. McAfee to Draper reporting interview with Mrs. Elizabeth Thomas, November 80, 1847. D.M. 86J88-40.

(14) George Rogers Clark "Diary," entry April 20, 1777. Illinois Historical Collections, VIII, 21; John Cowan Journal, entry April 25, 1777. D.M. 4CC30.

(15) Draper note in D.M. 36J1 reads: "See Mrs. Kenton's notes showing Linn and Moore to be chosen by lot." The original Kenton statement is in D.M. 6BB21-26.

(16) John Cowan "Journal," entry June 5, 1777, supra; Andrew Linn interview; letter John Chisholm.

(17)Ibid; Clark "Diary," entry June 22, 1777, supra; Andrew Linn interview; letter John Chisholm.

(18)Clark Memoir, supra.

(19)Andrew Linn interview; letter John Chisholm.

(20)Daniel Murray to Thomas Bentley, May 25, 1777. Kaskaskia Records, ed. by C. W. Alvord, Illinois Historical Collections, V, 8.

(21)Defense of Thomas Bentley, August 1, 1777. lbid., 12-16.

(22)The Sovereigns family were among the earliest white people in Kentucky. The name is spelled in various ways in early Kentucky records; for example, Severin Sovereigns, Sovarins, Soverain, Soverns, Severns. Ebenezer Severns was a member of Captain Bullitt's surveying party in Kentucky in 1778, and Ebenezer and John Severns assisted Douglass and Gist in making surveys there in 1775. John improved lands near Licking River that year. In 1776 Ebenezer raised a crop of corn on Soverin's Creek, a branch of Hingston's Fork. Gower Severns acquired land on the Beech Fork of Salt River a few miles from where Bardstown now stands, through living on it more than twelve months prior to 1778. John Severns was the most widely known of the family. After him was named Severns Valley Creek in Hardin County, and from this stream came the name of the Severns Valley Church located on land now included in Elizabethtown. For references to the above see Collins, II, 326, 357, 358, 511, 519, 549, 624; "Certificate Book Virginia Land Commission," in Register of Kentucky State Historical Society (January, 1923), 51, 59; ibid. (September, 1923), 189, 206. O. M. Mathers Explorers and Early Settlers South of Muldraugh Hill, ibid. (January, 1924), 31; James T. Tartt, History of Gibson County, Indiana, 48-49; Andrew Linn interview; Deposition of John Severns, January 6, 1804, in The Boone Book, Office Clerk Hardin County Kentucky; Deposition Samuel Haycraft, August 2, 1814, ibid; Severns vs. Hill, in Kentucky Reports, ed. by Bibb, III, 240.

(23)"Certificate Book Virginia Land Commission," Register of Kentucky State Historical Society (September, 1928), 189.

(24)Mann Butler, A History of the Commonwealth of Kentucky, 44; Andrew Linn interview; John Chisholm letter; Clark Diary, entry August 5, 1777; John Cowan Journal, entry August 5, 1777.

(25)Col. John Bowman to Gem Edward Hand, December 12, 1777, in Thwaites and Kellogg, Frontier Defense on the Upper Ohio, 181-183. Capt. William McKee to Gen. Edward Hand, December 81, 1777, ibid., 194.

(26)Clark to Hand, April 17, 1778, and Hand to Clark, April 22, 1778, Illinois Historical Collections, VIII, 44-45.

(27)Draper notes on Benjamin Linn. D.M. 36J36-40.

(28)Ibid.

(29)Carter vs. Oldham, Kentucky Reports, Hughes ed.; I, 354.

(30)John Chisholm letter.

(31)Draper notes on Benjamin Linn, supra.

(32)Clark Memoir, Illinois Historical Collections, VIII, 300.

(33)Ibid.

(34)Court Martial Book, llinois Regiment. D.M. 56J10-12.

(35)Draper notes on Benjamin Linn; Henry Wilson, dictation. D.M. 6J97.

(36)McAfee to Draper, November 30, 1847. D.M. 4CC84.

(37)"Certificate Book Virginia Land Commission," Register of Kentucky State Historical Society (September, 1923), 189, 216, 222.

(38)Ibid. (January, 1928 ), 28.

(39)Otis M. Mather, "Explorers and Early Settlers . . . ," ibid. (January, 1924.)

(40)Certificate Book Virginia Land Commission," Register Kentucky State Historical Society. (September, 1923), 206.

(41)John Chisholm letter.

(42)See n. 2; Spencer, History of Kentucky Baptists, 1, 17.

(43)James Veech, The Monongahela of Old, 101.

(44)Albert Henry Newman, "Baptists," in Encyclopedia Britannica, ed. eleven, III, 376.

(45)Spencer, op. cit., I, 102.

(46)Deposition by Squire Boone, in Otis M. Mather, Six Generations of LaRues - and Allied Families, Appendix A, 164-168.

(47)Deposition of John Severns, see n. 22.

(48)Spencer lists John Bailey as one of seven Separate Baptist preachers in Kentucky in 1785, in History of Kentucky Baptists, I, 102.

(49)See notes 45 and 46.

(50)Collins, II, 456-458; John Chisholm letter.

(51)Ibid.

(52)Collins, II, 456-458; Rev. S. H. Ford in Christian Repository, Louisville, Kentucky (October, 1856). D.M. 35J38-40.

(53)Letter W. H. Lynn, see n. 5.

(54)The Boone Book, see n. 22.

(55)Collins, II, 457.

(56) Harrison's Heirs vs. Deremiah. Kentucky Reports, Bibb ed., II, 349.

(57)Spencer, op. cit., I, 33-34.

(58)Ibid.

(59)Virginia Grants, Kentucky Land Office, Book X, 30.

(60)Spencer, I, 68.

(61)Ibid., I, 209-210.

(62)Deed Book IV, Office Clerk Nelson County, Kentucky, pp. 288, 294, 651; Deed Book I, Office Clerk Green County, Kentucky, 40.

(63)Among these is the marriage of James Cleaver to Hannah Linn December 29 1789. Hannah is identified as the daughter of Ben'amin s brother, Nathan, in the probate of Nathan's estate in Lincoln County, Kentucky, in 1785.

(64)Among these is the marriage of John Chism [Chisholm] to Esther Lynn, September 27, 1792, and of Joseph Philpot to Milly Lynn, April 29, 1797. Esther is identified in the John Chisholm letter as the second daughter of Benjamin Lynn. It is probable that Milly also was a daughter of Benjamin, as her name does not appear among the children of his brothers, James, William, Nathan, or Andrew, all whose progeny are known, The Green County records show that Marshall D. Spain was married to Rachel Lynn, by Manoah Lashley in 1798, but no day or month is given. Rachel may have been the daughter of William, as his will contains a bequest to a daughter bearing that name.

(65)Spencer says, "After laboring among the settlements between Salt River and Green River about twenty years, he [Benjamin Lima] moved to where his brother Willian3 had settled on the southern border of the State." (History of Kentucky Baptists, I, 17.) Spencer is wrong in naming William here, as William had been killed by Indians March 5, 1781. Nathan had been killed May 9, 1781, while defending the McAfee Station, and Andrew Jr. had died at his home in Pennsylvania as early as 1790. The brother in whom Spencer refers must therefore have been James, as he was the only one living when Benjamin moved to Green County. In 1784 James Linn and his father, Andrew Sr., sold the land in Pennsylvania on which they had been living. (See Deed Book A, Fayette County, Pennsylvania.) In the interview with Dr. Draper, Andrew of Cookstown says, "Andrew Linn, the elder, in his old age went to Kentucky to his youngest son, Benjamin, on Green River, where he died in 1800, aged one hundred." Andrew, of Cookstown probably should have named James instead of Benjamin here. James was married in Nelson County in 1788, and obtained title to land in Green County on which he had lived for some time. Green County was formed from Nelson. Since James and his father had owned property in common in Pennsylvania, it would have been only natural for theem to continue living together after moving to Kentucky.

(66)Spencer I, 251.

(67)Ibid., II, 608.

(68)lbid., I, 249.

(69)Ibid., II, 106.

(70)Newman, "Baptists," see n. 44; Autobiography of Barton W. Stone, 195.

(71)Andrew Linn interview.

(72)Deed Book A & B, p. 31, Madison County, Alabama.

(73)John Chisholm letter.

(74) Spencer, I, 17.

(75)Otis M. Mather to G. W. Beattie, July 28, 1921.

(76)Otis M. Mather, Six Generations of LaRues . . . supra, 152-158.

(77)Ibid., 83; A copy of the petition is in Mather's "Old Hodgenville." in LaRue County Herald, April 15, 1920.

(78)Andrew Linn interview; Miss T. L. Chisholm to Dr. Draper, March 10, 1848. D.M. 37J111. Miss Chisholm was a daughter of John Chisholm.

(79)John Chisholm letter.

(80)D.M. 36J36-40.

-George William Beattie And Helen Pruitt Beattie, Highland, California, "History of the Linns Of Kentucky, Part II, The Filson Club Historical Quarterly, Vol. 20, 1946, pages 137-161

Source: This information came to be made known to your webeditor in 12.2021. It was a chapter in a 1946 issue of The Filson Club Historical Quarterly. It is part two of a three part series. All three parts should be accessible through online search, but only the second part is pertinent to the Restoration Movement. Special thanks to C. Wayne Kilpatrick for sharing this information with us.

![]()

Chronology Of The Life of Benjamin Lynn

1701

Andrew Linn, Sr., (BL's father) was brought to America ‘as a babe in arms.'

1750

BL was born in Chester County, Pennsylvania

1767 or 1768

The Linns leave Maryland and move to SW Pennsylvania. Benjamin leave family (at 17) and goes into the forest region of Ohio to live among the Shawna (Shawnee), Delaware, Maumee (Miami in the Maumee Valley) and Kickapoo Indians. Learns languages and customs.

1774

BL helps settlers of Fort Harrod to strengthen fortifications against the Indians.

1777

Long siege of Fort Harrod, Ky by Indians (6 mos.) George Rogers Clark is in command at fort. Capt. Benjamin Linn sneaks out to eavesdrop on the Indian plans, brings back supplies to the fort, and even kills one Indian in a confrontation.

July 9, 1777

BL married Hannah Sovereigns at Harrods Station, now Harrodsburg, Kentucky during siege. She uses the Bible to teach him to read and write.

1780

BL leads expedition to Vincennes and then to Ohio against the Indians. Military career concludes.

1780

Kentucky still part of Commonwealth of Virginia, Governor Patrick Henry deed Benjamin Lynn 1000 acres of land on which his for had been constructed. (Land Records 10:3)

1782

BL formed a Separate Baptist Church near Nolin (No-Lynn) River in Larue County, Ky. There he baptized seven people, believed to be the first baptisms in Kentucky.

1792

The Linns change the spelling of their name to Lynn.

1798

John Chisholm married Benjamin's daughter Esther in Green County, Kentucky. Marriage Bond dated 27 Sep 1798. Bondsmen: John Chism [sic] and Marshall Spain. Married 27 Sep 1798 by Benjamin Linn. [Actual record uses the spelling of Lynn.]

August 1801

Attends and participates in the Cane Ridge Revival, Paris, Kentucky

July 1802

BL occupied a seat in the Green River Association of Baptist Churches

1803

BL is replaced as minister of the Brush Creek Baptist Church, having left the ministry of the Baptists. Somewhere around this time, BL is baptized by Barton W. Stone for the remission of his sins.

1809

With Lewis Bynam, BL ordains Samuel Boyd into the ministry of the Christian Church

1810

John and Esther Chisholm moved to just north of present day Huntsville, in Madison County, Alabama. The Lynn's follow soon thereafter.

1814

Early part of year, BL establishes a Christian Church in Huntsville, Alabama

December 23, 1814

Benjamin Lynn died and was buried in the church yard nearby.

1816

Family moves west to Lauderdale County, the Chisholms to a few miles north of Florence, and the DeSpains to the NW corner of the county, Waterloo. Soon thereafter, the church is established in both places.

![]()

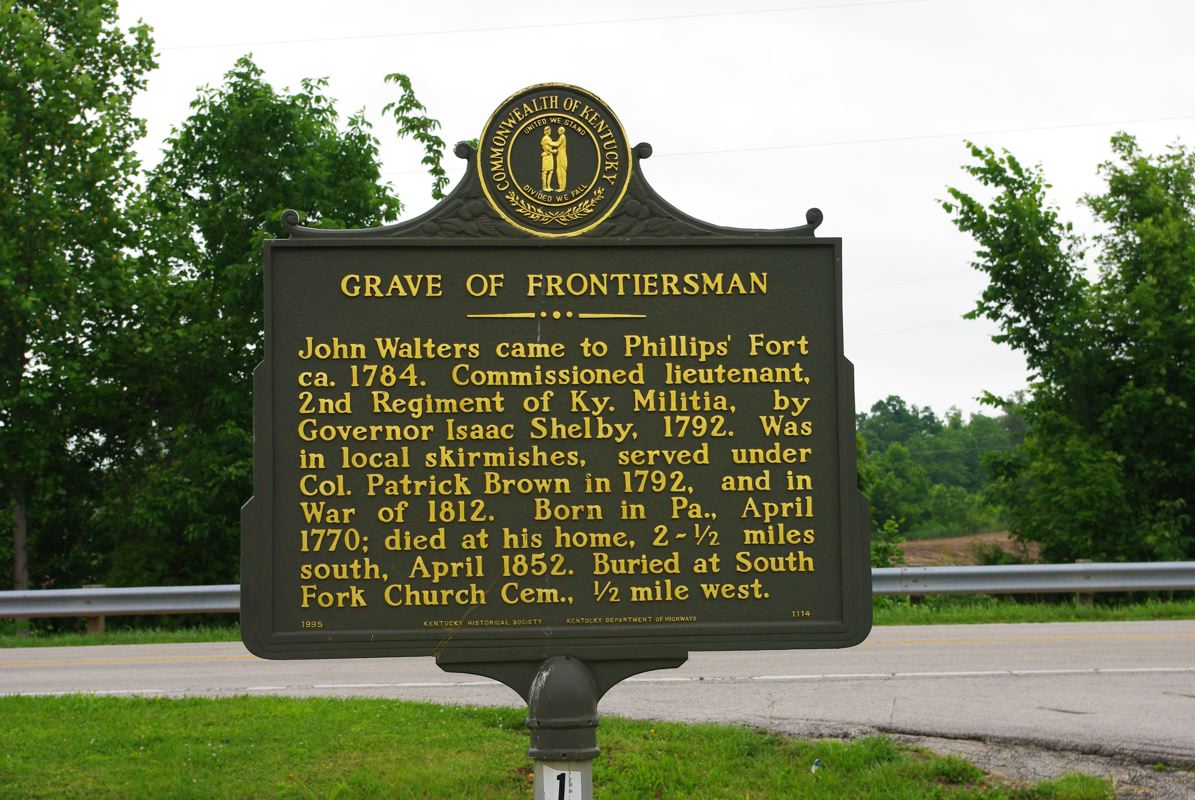

Grave Of Frontiersman

James Walters came to Phillip's Fort

ca. 1784. Commissioned lieutenant,

2nd Regiment of Ky. Militia, by

Governor Isaac Shelby, 1792. Was

in local skirmishes, served under

Col. Patrick Brown in 1792, and in

War of 1812. Born in Pa., April

1770; died at his home, 2-1/2 miles

south, April 1852. Buried at South

Fork Church Cem., 1/2 mile west.

Historical Markers GPS Location

37°30'13.0"N 85°44'16.3"W

or D.d. 37.503619, -85.737873

![]()

South Fork Baptist Church Location

SOUTH FORK church, originally called No-Lynn, was, according to tradition, constituted in what is now La Rue county, in the summer of 1782, by Benjamin Lynn and James Skaggs. The late venerable Elder John Duncan took much pains to learn the history of the church, and had conversations with at least two men who claimed to have been present when it was constituted. They stated that Lynn had been preaching in the neighborhood for some considerable time, and several persons had professed conversion. The church was constituted under the boughs of a large oak tree, where it continued to meet the remainder of the summer. Immediately after the organization was effected the church sat to hear experiences. Seven persons were approved for baptism. The times were troublous. It had been only a few weeks since the supposed massacre of Elder John Gerrard, in an adjoining neighborhood, and the Indians were now lurking in the surrounding forests. The candidates for the sacred ordinance were guarded to the water by armed citizens, and baptized by Elder Lynn, in No-Lynn [now spelt Nolin] river. If this account be true, it is probable that these were the first persons baptized in Kentucky.

This church first united with old South Kentucky Association, but, in 1797, it assumed the style of Regular Baptists, and afterwards became a member of the Green River fraternity. It was one of the few Baptist churches, in which the "jerks" and other extravagances prevailed during the great revival of 1800-3. It was subsequently divided on the subject of slavery. But a reconciliation beingeffected, it became very prosperous, under the ministry of William M. Brown. It is at present one of the largest churches in Lynn Association. Among the few preachers it has raised up was John Hodgen, a brother of the famous Isaac Hodgen.

-J.H. Spencer, History of Kentucky Baptists, Volume 1, pages 33,34

South Fork Baptist Church

Where Benjamin Preached

GPS Location of South Fork Cemetery

37°30'28.0"N 85°44'29.3"W

or D.d. 37.507777, -85.741473

![]()

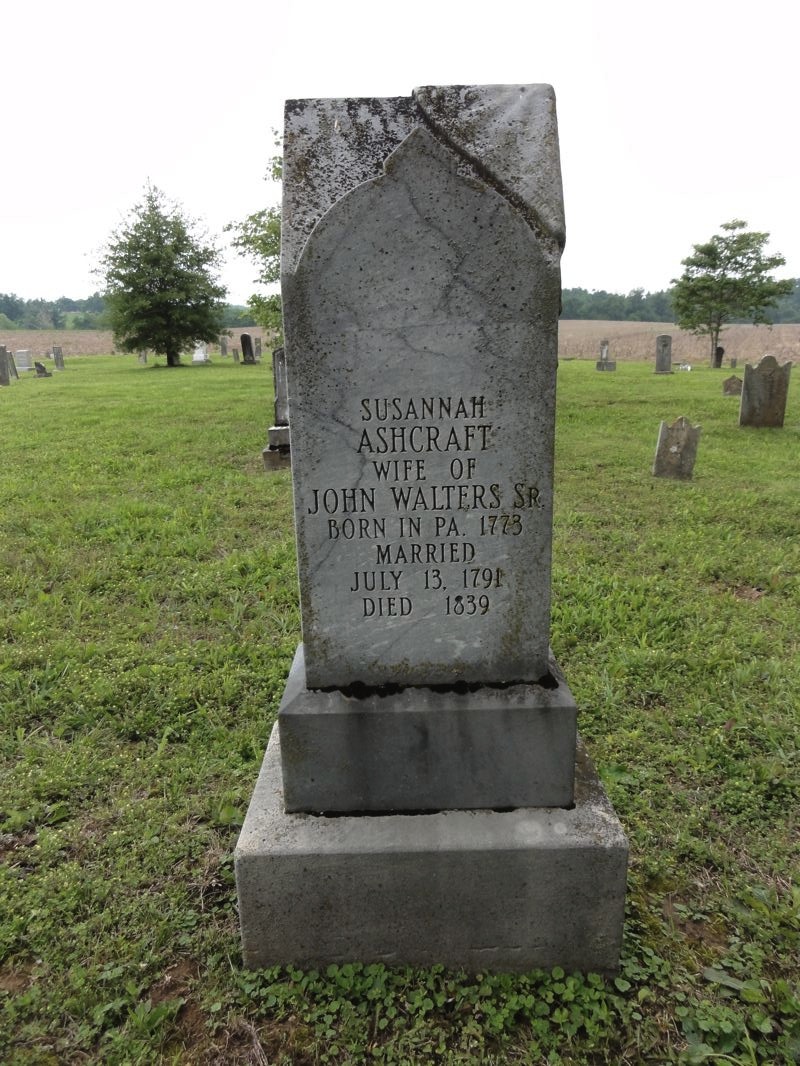

Buried At South Fork Cemetery Is

John Walters

An Indian Fighter Who Received Seven Wounds From Fights

He Was Mentioned In The Last Known Indian Battle On Buron's Run

![]()

Severn's Run 1792

A band of fifteen Indians attacked the Severns Valley settlement, killing two women and five

children, livestock and burning several cabins before moving northward. Fifteen settlers led

by Colonel Patrick Brown, set out in pursuit of the raiders. By nightfall they had tracked the

Indians to the banks of the Rolling Fork River where the Indians crossed. The settlers camped

by the river for the night without building a fire and with 2 guards posted. At daybreak they

resumed pursuit of the raiding party. They found the Indians had gone ashore on the opposite

bank. The settlers forded the river and quickly came upon the camp of Indians, which set between

the banks of the Little Branch (Brown's Run) and the Rolling Fork. They were able to surprise the

raiding party and a battle ensued, being a mixture of gunfire and hand to hand combat. At the end