Samuel Klinefelter Hoshour

1803-1883

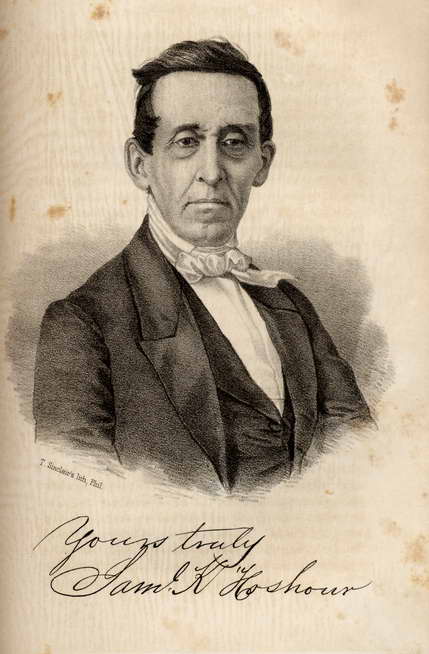

Samuel K. Hoshour

Very many persons are under the impression that the subject of this sketch is a native of Germany. This impression is incorrect. He was born in York county, Pennsylvania, on the 9th of December, 1803; and has never so much as stood upon transatlantic soil. His American ancestors, nearly a century before his birth, came from the vicinity of Strasburg on the Rhine; and their ancestry bad in them more of the French than of the German element. The immigrants to America, having settled in a community totally German, in time lost the French characteristics, as also the language; and at the time of his birth they spoke only American German.

Samuel K. was the oldest of six children; and in his fourteenth year he lost his kind father, who was in principle a Mennonite, though a member of no church. His mother was a Lutheran after "the straitest sect," conscientious in what she believed to be the will of God. Though a firm believer in Infant Rantism, she did not insist upon the sprinkling of her children, in opposition to the views of her husband, who regarded it as a relic of Popery. The neglect of this rite, however, did not prevent her from imparting to her first-born early religious instruction. On the contrary, whenever she had an opportunity, she would relate to him gospel facts, and teach him short, impressive prayers. On all proper occasions she took him to the house of God, and never failed to put into his pocket a copper for the congregational treasury, thus teaching him to practice Christian liberality, a lesson he has never forgotten.

At the death of his father, who left considerable property, he was placed under the control of a guardian in this, as in many other instances, a palpable misnomer. By this high-minded (?) guardian he was, for several years, hired out on a form at very low wages; for, owing to the density of the population, and the consequent slight demand for laborers, he, at the age of sixteen, could obtain only four dollars a month for his services.

His residence among strangers as a hireling was not by any means favorable to the development of either his moral or intellectual endowments. He went to school but little, and as he had greater fondness for extracting the finny tribes from their element and opossums from their retreats, than for extracting ideas from books, he spent the most of his time in the first-named employments; nor did his views of the sanctity of the Sabbath at all interfere with such pursuits even on that day. Under such circumstances, his progress was so slow that at the close of his sixteenth year he had not quite reached the "rule of three," which, in that day, was generally regarded as the ultima thule-the last island-in the ocean of scientific truth.

About this time his guardian and relatives concluded that he ought to learn a trade; and he was required to make choice of his pursuit. To him the county in which he lived was the world; so with his limited vision he surveyed hastily the several employments of his neighbors, and decided in favor of the tanning business! It was accordingly arranged that he should be indentured to learn the trade of his choice, at the beginning of the year 1880. But what a trifling incident often changes the direction of human life, and conducts to a different destiny the immortal soul!

During the summer of 1819, he was hired to the owner of a large grist mill, in which he was usually employed on such days as were unfavorable for outdoor pursuits. The proprietor of this establishment was a better miller than bookkeeper; and, as his employee could write a legible hand and repeat the table for dry measure, he set him to posting his accounts, which work was satisfactorily performed.

In the Fall of that year the citizens expressed great apprehensions that they should be without a school the ensuing Winter; for the old Swiss gentleman, who, for years, had been wont to teach in the Winter, and in the Summer go into parts unknown, mending old clocks and soldering leaky tinware, had not returned at his usual period.

"One morn they miss'd him on the

accustom'd hill,

Along the heath and near his favorite tree."

As the mill was the rendezvous of the leading minds of the community, their apprehensions were often expressed in the hearing of the miller, who one day found means to quiet their fears: said he, "Here is Sammy Hoshour, who can write a pretty good hand, can multiply and divide, and reduce pints to bushels: he can control the small ones, and if larger ones will not obey let them be kept at home. This proposition pleased many, but some doubted. However, necessity and the miller's influence invested him with the birch, the symbol of school-room authority in that day. He was then seventeen years old; the community was purely German; and he knew no English save a few sentences gathered from Yankee tin-peddlers. Contrary to his own expectations and those of the doubting ones, his didactic administration was a success, and gave general satisfaction.

It was expected that, at the close of the term, he would relinquish the birch and enter upon his apprenticeship; but when the time arrived he had forty dollars in his pocket, a spirit of inquiry had been awakened in his mind, and he had caught the scent of something more agreeable than a tannery. He therefore changed his former purpose, with the consent of his guardian, and determined to procure, with the proceeds of his school, some further scholastic attainments.

This resolution, though he knew it not, was an important step in his life, it was the beginning of his literary career. He soon after entered, for the first time, an English school, being then a stalwart, awkward, and verdant rustic. His first recitation was so unique and so germanic that it subverted the gravity of both teacher and pupils. Yet, submitting with stoical indifference to these slight discourtesies, he remained in the school until he obtained a fair knowledge of arithmetic, and a slight acquaintance with the nonsense, as he supposed, of English grammar. His money being exhausted, he returned for awhile to the plow; and on the approach of winter he entered upon his second administration as teacher.

In his eighteenth year he united with the Lutheran church. Soon after this event, a copy of Pilgrim's Progress fell into his hands, which was the first book he ever read through. Besides the religious influence it exerted upon him, it stimulated his desire of knowledge. Believing that sacred knowledge was best of all, and that the Christian ministry was the repository of it, he greatly desired the requisite qualifications for entering into that vocation.

His guardian, being a Mennonite, and opposed to a learned ministry, refused to furnish him with the means of further educating himself; but a wealthy maternal uncle, who was a staunch Lutheran, consented to supply him with money until he should possess his patrimony. He then entered an English classical school of high repute at York, Pa. His highest aspiration at that time was to become a good German preacher. The idea of ever addressing English audiences had not yet entered his head.

But English declamations were required in the school, and when his day came all the pupils were eager to hear the "Dutchman." Having determined to make up in spirit and sound what he lacked in orthoepy and infection, his speech was well received; and as he passed out the Professor encouragingly predicted that, by proper effort, he would become a good English speaker. From that moment he sought to become English, and with such success that one cannot now detect the slightest German accent in his pronunciation.

In this Institution he completed about an equivalent to the regular college course to the close of the sophomore year. Here, too, by excessive study, he so seriously impaired his health, that his advisers urged him to change his location. Accordingly he repaired to the Theological Institute at New Market, Virginia, then under the control of Prof. S. S. Schmucker. By more temperate study, by frequent exercise in the rugged sections of that county, and by a free use of the mineral waters of that region, he partially recuperated his overtaxed powers, and was enabled to complete the course of study there pursued, which course embraced the collegiate studies of the junior and senior years, in connection with theology, theology, not according to the Bible, but according to the standards of the Lutheran church.

At this time the Principal, Prof. Schmucker, was elected Professor of Theology in the Theological Seminary at Gettysburg, Pa. Besides his duties in the Institute at New Market, the Professor had served three small congregations as their pastor. His flocks were so much attached to him that they refused to let him go, unless he would first provide an acceptable substitute. As it was necessary, in this pastorate, to officiate in both English and German, and as no other of the many students could do this so well as Elder Hoshour, he was nominated and received as the successor of Professor Schmucker.

In the same year, 1826, he was married to Miss Lucinda Savage, daughter of Jacob Savage, Esq., of New Market, Va.

Tenacious of the traditions of his theological fathers, fully impressed with the greatness of the Lutheran church, and not a little inflated by the fact that he had been counted worthy to wear the mantle of his preceptor, he entered upon his clerical duties with great zeal for God, though with very little knowledge of His word. In the pulpit he was not always mindful of Paul's admonition "to speak the things that become sound doctrine." Like too many young preachers he estimated the value of his preaching, not by the number of correct and lasting impressions made on the minds and hearts of his hearers, but rather by the excitement they manifested, and the quantity of tears they shed. Hence, in the preparation of his sermons, he collected all that was terrible in the domain of fear, and all that was touching in the realms of love and suffering. Then, as now, this style of preaching was popular; and, like Ezekiel, he was to the people as a very lovely song of one that hath a pleasant voice, and can play well on an instrument."

His fame soon extended eastward; and, in 1828, he received and accepted a call from a congregation in Washington county, Maryland. In this place, also, he was popular among all sorts and classes. Such, indeed, became his reputation, that in about two years he was invited to follow his old preceptor, and take charge of the congregation at Gettysburg, Pa., the seat of Pennsylvania College, and also of the Theological Seminary of the General Synod of the Lutheran Church. But his Maryland charge so heartily remonstrated against his removal that he consented to stay with them.

His pastorate was about eight miles from Hagerstown, the county seat, in which there were at that time about five thousand inhabitants, among whom Lutheranism was the predominant religion. Among others was a large and influential congregation which had been for years under the pastoral care of Dr. B. Kurtz. Owing to his proximity to this place, Elder Hoshour frequently occupied the Doctor's splendid pulpit, and so acceptable were his ministrations that, in 1831, he became their pastor, Dr. Kurtz having been called to another field of labor.

In his stipulations with the "Council" relative to his pastoral duties, there was one feature that greatly assisted him to become a heretic, if indeed he is one. It was made a part of his duty to lecture each Wednesday evening on the Holy Scriptures; and, in order to fulfill this part of his engagement, he was compelled to study the Scriptures in their proper connection. This he had never done before, though he had been preaching for five years; for, in the theological seminary, he had taken the regular course prescribed in such institutions, that is, to study human dissertations upon theology, church history, the art of sermonizing, etc., and to examine the Bible only as referred to by the standards of the particular sect! But in performing this new duty, he entered into the school of Apostles and Prophets. He began lecturing alternately on Matthew and the Acts of the Apostles, expounding the doctrine in the light of the context, and giving copious geographical delineations, accompanied by the history of places and events. Proceeding in this way, it was not long till he entertained the opinion that the religion of the Bible was very different from that in popular repute. He perceived that the former was sober, solid, a matter of principle; while the latter was full of excitement, vapory, and not a little unscrupulous. He became daily more enamored of the ancient gospel, and less confident in the popular theology; more desirous of the sincere milk of the word, and less concerned about the tenets of his church. His preaching grew more and more evangelical, and soon the light of the great Luther was almost lost in the brighter effulgence of the Apostle Paul.

In preparing the last class of catechumens for "confirmation," he used the catechism very sparingly, but required them to commit to memory large portions of the New Testament. On the day of confirmation he did not use the liturgical form, but confined the ceremony to the 24th verse of the 16th chapter of Matthew, the import of which he had previously explained to the candidates. This departure from the usages of the Lutheran fathers met no opposition, such confidence had the congregation in the knowledge and integrity of their pastor.

In his further investigations of the Scripture he began to call in question of the consequences ascribed to the fall of Adam, and especially did he become intolerant of the Calvinistic view of that subject. The ability or inability of the sinner was a subject upon which he bestowed much thought.

While reflecting upon this subject he made a visit to his father-in-law's, at New Market, Va., where there came into his hands, one day, three numbers of the Christian Baptist. Of the editor, Alexander Campbell, he at that time knew but little, nor was he by any means favorable to the views of the Baptists. Yet he glanced at some of the articles, and was better pleased than he anticipated with both the style and the matter. One article especially, on The Natural Man, (I. Cor. 2,) he read with no common interest, for the thoughts therein expressed were very similar to some that had flitted through his own mind. In a few weeks he returned to Hagerstown, and resumed the regular routine of his pastoral duties, but still that article on the Natural Man, like the ghost of murdered Banquo, continually confronted him.

Thus matters went on till the Spring of 1834, when an event took place which wrought a change in his views of Baptism and in the aspects of his whole future life. About six miles from Hagerstown was a densely populated region called Beaver Creek, rich in things material, but poor in things spiritual. A large school-house was the usual place of preaching, and prior appointments took the lead in its accommodations. Most of the different sects had a few adherents in that region, who occasionally procured the services of their respective ministers. Elder Hoshour frequently preached to them the Lutheran gospel; Methodists, Episcopalians, United Brethren, and Tunkers also visited them; but none were successful in making proselytes.

In the Spring of 1834, an unexpected religious commotion occurred in the Beaver Creek region. A new preacher made his appearance, dauntlessly advocating views that negatived a great amount of the previous preaching at that point. He called himself a disciple of Christ, but as he distributed copies of the Millennial Harbinger, the sects called him a Campbellite. He soon made an impression upon some minds that had hitherto been regarded as impregnable. His very success created great opposition, yet with Peter's boldness he continued to proclaim the ancient gospel without much deference to the religious leaders of the day, whom he hesitated not to challenge to the defense of their tottering systems. "The common people heard him gladly," and he was not long in making proselytes to "the ancient order." Persons of superior standing in the community, who, the clergy supposed, never would consent to be "dipped," did submit to immersion, evincing unmistakable sincerity in their profession of the Christian faith. In a few months over forty persons were immersed, and an active church established at Beaver Creek, on the foundation of the Apostles and Prophets.

The fame of this preacher spread far and wide, but as he was regarded by the orthodox as an arch heretic, Elder Hoshour in his clerical dignity would not honor "such a fellow" with a hearing. But he listened to the accounts given of him by others, and when informed that the preacher taught that all spiritual influence, in order to conversion, is exerted through the word, he would pleasantly observe: "He is for all word, the Methodists for all Spirit, both extremists, but we Lutherans occupy the middle and true ground, contending for both word and Spirit."

There was at this time a Lutheran brother with whom Elder Hoshour had lived in fraternal intimacy for several years. He had been "converted" at a great Lutheran revival, and had spent considerable time in preparing himself for the ministry; but being, like Moses, "slow of speech," he devoted himself to teaching. While the revival was progressing at Beaver Creek he became the teacher in the spacious school-house in which the meeting was held. He therefore almost necessarily became a bearer of the new heresy. Having formerly been a boarder in the house of Elder Hoshour, and being much attached to him, he often visited him at his parsonage in Hagerstown. In the course of one of their interviews the pastor asked him how the Campbellites were progressing. He replied that they were still immersing some; "and," said he, "I tell you there is more truth than poetry about those people after all. I have learned more from them about the order in which the Scriptures should be read; more about their proper divisions and the special object of each division, than our ministers of systematic theology ever taught us. I say this," continued he, "with all deference to you. I have enjoyed your ministrations; but the theory to which you are wed will not permit you to represent matters as those people do." "Ah !" said the Reverend Mr. Hoshour, "I fear you are almost persuaded to be a Campbellite." "No matter," replied the other, "I intend to honor and obey the Saviour as I understand Him in his word."

Thus ended their interview, and ere long the pastor heard that his friend had been immersed, and had become an ardent advocate of the ancient gospel. In a short time the apostatefor so he was regarded by the orthodox, made a second visit to his friend Hoshour, who asked him his reasons for leaving the Lutheran Church. Among other reasons assigned he said that during his membership in that church he had never been taught the connection between Luke xxiv. 46, 47, and Acts ii. 38, that when anxiously seeking the pardon of his sins he had never been directed to Peter's answer to the question, "What shall we do?", in a word, that Christian Baptism had a significance, a design, which the Lutheran pulpit entirely ignored. This was a startling revelation to the questioner, for, although he had been fur nine years a preacher in the oldest Protestant church, the connection between the passages above referred to had never engaged his attention.

We must conclude that very many prominent preachers of the different denominations are equally ignorant to this day, else we cannot charitably regard them; for they do not teach this connection, and if they understand it and yet preach it not, they are guilty of "handling the word of God deceitfully."

This statement of reasons naturally led them into a discussion of Baptism. On the design "for the remission of sins" they had no controversy, for that is a cardinal doctrine in Luther's catechism and in other formularies of the church he founded. Though the doctrine was believed by Luther, it was entirely overshadowed by the unwarranted prominence given to faith. This was somewhat pardonable in him, for human nature is prone to extremes, and in avoiding the formalisms and penances of the Pope he overleaped the commandments of Jesus Christ. His errors may be overlooked, but his successors are without excuse.

But, to return. The subject and the "mode" of baptism were not so easily disposed of by the two friends. On these they joined issue, hut the discussion closed without any immediate results of importance.

During the interview, however, Elder Hoshour obtained some facts relative to the teachings and practices of the Christians that seemed rather significant. Yet with respect to the "mode" of baptism he regarded them as ultra. The Theological Institute, though it had failed to acquaint him with the Scriptures, bad not neglected to furnish him with the stereotyped objections to the universal prevalence of immersion. The varieties of climate; the scarcity of water in certain localities; the inconvenience and indecency of the practice; its incompatibility with the easiness of Christ's yoke, all forbade the conclusion that immersion is the only Scriptural baptism! Rut he was soon to be dispossessed of all this opposition to the truth.

Early in the Summer of 1834 his ministerial duties led him a few miles beyond Beaver Creek, where the troublesome meeting was still in progress. On the way he met a Methodist friend who at once beset him with a representation of the ruinous influence of the "Campbellite" preacher. He stated that the class-leader had encountered the preacher in debate; that he had been vanquished; that he had gone over to the enemy; that their class was about broken up; and that the preacher was more defiant than ever. "Now," continued the speaker, "he must be withstood, and you are the man to oppose him successfully, for I once heard you preach on the conversion of the eunuch, and I think you showed plainly that it is not certain that he was immersed." This flattering invitation he did not then accept, but promised to consider the matter.

Having joined two loving hearts in the bonds of matrimony, he set out for home. As he rode along he meditated upon what had been told him until the fire of controversy burned within him. But prudence whispered to him that, before he consented to meet this Goliath of the "Campbellites," he had better examine his sling and be assured that he had a sufficient number of missiles to prostrate the giant. In obedience to this timely suggestion be resolved to examine the whole subject of Baptism, and to supply himself with all the arguments pro and con. 0 that every preacher in Christendom would do likewise, with regard to that and every other point of material difference I Then would the truth have free course and run and be glorified! Then would God also be glorified in the salvation of souls! Then would the followers of Jesus be joined together in one mind, speaking the same thing! Then would infidelity perish and the world would believe that God had sent his Son to be their Saviour! But alas! "this people's heart ha8 waxed gross, their ears are dull of hearing, and their eyes have they closed."

In his investigation, he resolved to begin with the fathers and standard authors of his own church. He first consulted the voluminous works of Luther, in the original German; and, on the two thousand five hundred and ninety-third page of the tenth volume, he found Luther's sermon on Baptism, preached in June 1520. The very first page of this sermon put him in possession of a fact hitherto unknown to him, viz., the meaning which Luther attached to the German word "taufe." The following is a literal translation of the passage:

"In the first, place, Baptism in the Greek language is called Baptismos (Baptismos) and, in the Latin, Mersio, that is, as when a person dips something entirely into the water, the water will cover it; and although in many places, it is no more the custom to push the children into the font and dip them, but only to bepour them with the hand out of the font, yet it ought to be, and would right, that a person should, according to the signification of the word "taufe," WHOLLY SINK the child or candidate into the water, and baptize and draw it out again; as the word "taufe" comes from tiefen, as when a person sinks one DEEP into the water and dips."

After reading this passage, penned by no other hand than the great and authoritative Luther's, he wisely concluded that if it should happen to be in the possession of his opponent it would prove a formidable weapon.

The next standard author consulted was Dr. Mosheim, a Lutheran also, and a historian of high repute. On the 108th page of his Church History he found the following vexatious passage:

"The sacrament of Baptism was administered, in this (the first) century, without the public assemblies, in places appointed and prepared for that purpose, and was performed by an immersion of the whole person in the baptismal font."

The next author was Michaelis, one of the most learned men of the Lutheran church, who, on the 506th page of his "Dogmatic" expresses himself as follows:

"The external act of Baptism is dipping under water. This the Greek word Baptizo signifies, as every one acquainted with the Greek language must admit. The baptism of the Jews was performed by immersion; so also was that of John the Baptist, and of the first Christians. Of this we have a proof in the fact that baptism without immersion and only by pouring was allowed in case of the sick, in the third century, and it met contradiction as an innovation. * * * Immersion was practiced till the thirteenth century, and it is desirable that the Latin church had never allowed a deviation from this. But it (the deviation) did occur, and at the Reformation it was not altered, that is, changed to its primitive form."

Weighed down by these stubborn facts from the writings of the fathers, he abandoned the idea of meeting the defiant Goliath. Like David encumbered by the armor of Saul, he said, "I cannot go with these."

The result of his investigation was a firm conviction that immersion in water is the only Christian Baptism. In the mean time a better understanding of the New Testament and of the Constitution of the Church of which the Saviour said, "I will build it," had exhibited to him the futility of infant membership.

Here he found himself surrounded by circumstances that could not but severely test his piety and his moral courage. The beloved pastor of a large and influential congregation, living in fine style and receiving a good salary, a splendid prospect spread out before him and his children, yet no longer a believer in the doctrines he Waa expected to preach, dissatisfied with his own baptism, his conscience pleading for adherence to the right and fidelity to the word of God, he was in a condition to be fully realized only by those who have passed through a similar process.

Finally, like Moses, he chose to suffer affliction with the people of God, rather than to enjoy the pleasures of sin for a season. He resigned his charge without, at that time, revealing the special reason; and, in September, 1834, officiated for the last time in the splendid pulpit of his beloved congregation. These were to him dark days and at times his spirits were greatly depressed; but he leaned on the word of the Great Shepherd, His rod and His staff, they comforted him.

Though he could no longer preach, conscientiously, the Lutheran gospel, yet he did not immediately obey the gospel of Christ. His faith in the former system having been destroyed, his mind was reduced to a kind of chaos, and it required a little while for apostolic order to appear. It was not till the last Lord's day in March, 1835, that, without the knowledge of his family, he was immersed in the vicinity of Hagertown, Md. On reaching home his wife was greatly distressed, both because she was yet much attached to the Lutheran church, and because, with a mother's solicitude, she saw in the future nothing but penury and "the cold world's proud scorn" for herself and her little ones.

In the town he was the principal theme of conversation. Many denounced, some pitied, and a few commended him. As he walked up the street on Monday morning, none of his former brethren appeared to recognize him. Like Caesar,

"But yesterday he might have stood

against the world,

Now, none so poor as to do him reverence."

The Presbyterians passed him coldly, all because he had demonstrated his genuine piety by forsaking all for Christ's sake and the gospel's. None but the Episcopal minister gave him so much as a gentlemanly salutation. Nor were these the only chilling influences that he had to encounter. A pious mother that had taught him the first lessons in religion, maternal uncles who had taken a lively interest in his education, and were proud of his pulpit performances, brothers and sisters who were strongly attached to him as a champion of the Lutheran faith, were all in their turn to be confounded. In his interviews with them he made good use of the word, and expounded matters in such a manner that, although they would not obey the gospel, they could not severely chide him for having obeyed it.

Soon after his immersion, he left Hagerstown, and resided temporarily with his father-in-law at New Market, intending to emigrate to the West the ensuing Fall. During his sojourn at New Market, where he had been installed as pastor nine years before, he often met the sheep of his first flock. To them, also, he had become a stranger, wbose voice they were no longer willing to hear. The doors of his old church were closed against him; but the Baptists, out of personal respect, opened to him their house. When he preached on the action of baptism they were delighted; but when he pressed upon them the design, they manifested a spirit closely akin to that of the Athenians, when Paul declared to them the resurrection of the dead, (Acts xvii. 32.)

During the three months that he remained in that vicinity, he preached every Lord's day, wherever he could obtain a hearing. At the close of the last sermon at New Market, a highly respectable lady, a member of the Lutheran church, came forward and made the required confession. It was announced that she would be immersed on the next morning. Returning home, his father-in-law met him on the pavement, and informed him that his wife, Mrs. Savage, intended to be immersed at the same time. On the banks of the stream, at the appointed hour, she made the confession which is "unto salvation," and, with the other woman, was buried with the Lord in baptism.

Some time before this, as he was returning home from an appointment, his wife met him in the hall, saying, that she had been studying the New Testament, that she was satisfied that he had done right, and that she intended erelong to follow his example. Accordingly, on the next day after the baptism of her mother, she and three others, one of whom was also a Lutheran, were immersed in the same stream. Nor were these only immersed, they all arose to walk in newness of life.

Prior to his departure for the West, he spent three weeks preaching in the vicinity of Hagerstown, among his former acquaintances. In this time he immersed eleven persons, of whom five were Lutherans, two Methodists, and four "from the world." At sunrise of the last morning that he remained, he immersed the two Methodists, who both came up out of the water shouting and praising God. Yet this was heresy!

Finally, on the 16th of September, 1835, he set out for the West. While he was on the way, the Synod of Maryland met; and although he had consented, at the request of the Secretary, to withdraw privately, yet that august body formally and solemnly excluded him as a dangerous errorist. The following is a transcript of the original bull of excommunication, taken from the "Minutes of the Evangelical Lutheran Synod of Maryland, held at Woodsborough, Frederick county, in October, 1835:"

"The committee on paper No. 1 now reported, and, after some discussion, it was:

"Resolved, That the Rev. Mr. Hoshour, having changed his religious creed in some of the essential and fundamental articles of religion, as held and taught among us, has thereby voluntarily separated himself from all connection with the Lutheran Church, and cannot longer be considered a member.

"Resolved, also, That the Synod, for the above reason, expunge the name of S. K. Hoshour from the list of its ministers; that it no longer considers him a member of the Lutheran Church, and that he may live to see, feel, and acknowledge his errors, is the prayer of all chose to whom he was once ardently attached."

Such was the last step in his final exodus from the "Evangelical Lutheran Church."

On the 16th of October, 1835, he arrived, with his little family and less means, at Centreville, the county-seat of Wayne county, Indiana. His object in coming West was to procure a small farm, and, "in the sweat of his face," make an independent though humble living. But be soon found that his literary pursuits and sedentary habits had . greatly disqualified him for the business of a farmer. He no longer enjoyed it as he did, when an unlettered swain in Pennsylvania. Therefore he soon abandoned the plough, and commenced teaching a district school near Centreville at twenty dollars per month, an unprecedented salary in that day. Such was his success that, in a short time, he was elected Principal of the Wayne County Seminary, in which he taught four years to the entire satisfaction of the community.

During all this time, he employed his Lord's days in disseminating the simple gospel as he had learned it and most devoutly cherished it. In Centreville, the court-house was his sanctuary, in which he officiated as both preacher and sexton! On Saturdays he prepared the wood, and on Sundays made the fires and preached. His audiences were mostly composed of the more intelligent non-professors, and the more liberal adherents to the several sects, who were generally attentive, and disposed to approbate his preaching.

The Reformation was then in its infancy at that place. There was only one family, a man and his wife, that openly adhered to the cause for which Elder Hoshour plead. These, himself and his wife, at that time constituted the Church of Christ at Centreville. He acted as bishop, the lone brother as deacon, and the two wives as deaconesses! There was, therefore, little cause of strife and division in that church for each member has an office.

Though there were no contentions within, it was not long until he felt from without the sharp pints of sectarian bigotry and intolerance. Low chicanery and tact were resorted to in order to counteract his influence in the pulpit. But he occasionally made a proselyte, and by the help of others succeeded in building up a good and substantial church at that place.

After he had been there one year, the Baptists, many of whom sanctioned his preaching, insisted upon his uniting with them. He consented to do so, provided they would allow him to urge upon all "seekers," Peter's answer to the question, "What shall we do?" Acts ii. 37. To this there was some objection, and the union did not take place.

In the process of time, the majority of the Baptists united with the Christians, to whom they delivered over their commodious house of worship.

In 1836, the Legislature of Indiana appointed him a member of the Board of Trustees of the State University, at Bloomington, in which capacity he served very efficiently for three years.

At the Annual commencement of 1839, the Faculty and Trustees of that Institution conferred on him the honorary degree of A. M.

With Dr. Wylie, the late distinguished President of the State University, he enjoyed an intimate and most agreeable friendship. They communed freely on the subject of religion, and the doctor interposed but few objections to the views of his friend. He afterwards published a small work entitled: "Sectarianism is Heresy," which, possibly, was suggested by what occurred in some of their interviews. At any rate he was not a man who closed his ears against the truth, as the following incident will show.

On one occasion, in Commencement week, the chosen speaker for a certain evening did not arrive. The college chapel being crowded to overflowing, President Wylie invited Elder Hoshour to supply with a sermon the place of the anticipated speech, at the same time giving him liberty to choose his own theme and speak his mind freely. He accepted the invitation; took, as his subject, Man's Duty, Ecc. xii. 13, and proceeded to preach the ancient gospel to perhaps the largest and most intelligent audience he ever addressed. There were seated around him, on the rostrum, President, Professors, the Board of Trustees, the Executive of the State, and several literati from abroad; while before him were the elite of Bloomington and many visitors from various parts of the Commonwealth. He was then in the vigor of his manhood, and the discourse is said to have been one of great power. It was doubtless the masterpiece of his whole life.

In the Fall of 1839 he removed to Cambridge City, where he became the principal of a large and tastefully-constructed seminary. There he taught for seven consecutive years, and always had a large number of pupils, many of whom were from abroad. Several of Indiana's distinguished sons were educated in his school, among whom were Major General Lewis Wallace, and the present efficient Executive, Governor Oliver P. Morton.

During his residence at Cambridge City he preached on Lord's days either in the village, or at points from which he could return in time for school on Monday morning. Himself, his wife, and one brother in Christ then composed the church at that place. Thus it happened a second time that his flock were all officers! But they relied on the promise, "Where two or three are met together in my name, there am I in the midst of them."

With this weak force he had to combat strong opposition to what was stigmatized as Campbellism. As a teacher the several sects esteemed him highly, but upon his preaching they looked with suspicion, if not with contempt. Under all these discouragements he continued to preach plainly, scripturally, and sometimes polemically; but being afraid of building, on the apostolic foundation, "wood, hay, or stubble," he refrained for a long while from any attempt to proselyte. Still he immersed the first year some half-a-dozen substantial members, and the second year about as many. In 1848 he procured the assistance of Elder John B. New, and held a protracted meeting, which resulted in twenty-five additions, most of whom were persons of means, intelligence, and moral worth. Built up in that way, the church at Cambridge City has not yet fallen down; on the contrary, it has been enlarged from time to time, and is at the present writing in a prosperous condition.

During the eleven years that Elder Hoshour taught at Centreville and Cambridge, be preached every Lord's day except ten; often riding long distances after night-fall, through mud, and rain, and cold. During the greater part of this time he preached twice each Sunday; and for all these faithful labors, which shattered his constitution and destroyed his physical comfort for life, he received less than five hundred dollars, not fifty dollars per annum.

About the year 1846 declining health compelled him to abandon the school-room, with limited means and a family of seven children. For the support of his family he afterwards resorted to teaching the German language in the various Institutions and larger towns of the State; but, for the benefit of his race, he continued to preach the gospel almost without money and without price," as he had done for a score of years. Though but few men gave unto him, he desired to share with all men the unsearchable riches of Christ. Though he himself met with few real sympathizers, his own heart swelled with sympathy for all whose errant feet he found in the way of death.

In 1852 he purchased a small farm near Cambridge City, where he expected to pitch his tent for the remainder of his life, and give himself more fully to the work of the ministry. But being strongly importuned to aid in the construction of the Richmond and Indianapolis Railroad, he invested largely in this, to him, unprofitable enterprise. On account of this investment he became involved in debts, to extricate himself from which he was compelled to sacrifice the rural home which he had provided for his old age.

In June, 1858, he was elected President of the North-Western Christian University, located at Indianapolis, Indiana. In this capacity he served three years, at the expiration of which time the Institution was re-organized, and he became Professor of Modem Languages, the position which he desired, because it was far less laborious, and more suitable to his taste and genius. The functions of that office he still discharges to the credit both of himself and of that department of the University. In vacation he goes about proclaiming the word, and during the session he occasionally preaches in the city sometimes for the congregation with whom he worships, more frequently for the German Methodists, in their own language, and not unfrequently "so amiable a heretic is he" for his first love, the Lutherans.

But, ere long, he must rest from his labors. Already the almond-tree begins to flourish, and the grasshopper to be a burden. Already the strong men begin to bow themselves, and those that look out of the windows to be darkened. Soon shall the silver cord be loosed, the golden bowl be broken. Soon shall he go to his long home, and the mourners go about the streets. No man is more ready to be offered up, for without once having put off the armor of God, he has fought a good fight. Though nearly a11 else has been sacrificed, he has kept the faith, and strong in that faith he will descend to the tomb,

"Like one who wraps the drapery of

his couch

About him, and lies down to pleasant dreams."

Elder Hoshour is a frail, homely man, of an air decidedly

German. His stature is five feet nine or ten inches, and his weight about one

hundred and forty-five pounds. He has a sallow complexion, a highly bilious

temperament, raven black hair, and dark hazel eyes, full of subdued lire. His is

a singularly shaped head, which, upon the whole, is an unfair index of his

intellectual ability. His mind is of the reflective caste, active, logical,

comprehensive, and still vigorous, though impaired by the infirmities of the

flesh. If its power be estimated, philosophically, by the resistance it will

overcome, or the height to which it will elevate a given body, it will be found

to be greatly above the average. In its escape from theological darkness to

biblical light, it overcame early prejudices, clerical pride, family and church

affinities, and all sectarian restraints in the form of liturgies

and creeds; and despite the force of that gravity which, in this unscrupulous

age, drags down the conscientious man, it has elevated its possessor from the

obscurity of a German orphan boy to a conspicuous rank among the ministers and

educators of the age.

As a scholar he deserves honorable mention. The principal events of the world's history, and a general knowledge of the several sciences, are carefully stowed away in his retentive memory; and one will not easily approach him with any subject on which he may not converse intelligently. He reads five different languages and fluently speaks three, the English, the German, and the French. He is not fond of speculative theories, but drinks oftenest and deepest at the sacred fountain: hence his knowledge of the Scriptures is deep and extensive.

Since his entrance into the Reformation he has never been a sensation preacher. His forte has been to edify the church; to "enlighten the eyes of their understanding," that they might know "what is the hope of his calling and what the riches of the glory of his inheritance in the saints." He has, however, proselyted a goodly number to the faith of the gospel; but very few, if any, of whom have returned to the beggarly elements of the world. Those whose hands he puts to the plow seldom look back.

In the pulpit his style is somewhat peculiar. "Teaching and preaching" is his motto; hence, after singing and prayer, he usually expounds a chapter; after which another hymn is sung and he rises to preach. To the eyes of stranger this habit sometimes presents him in a false light, as the following anecdote will show: On a certain occasion an ex-member of the Indiana Legislature, who was also a disciple, was giving his opinion of President Hoshour. Said he, "I went, one day, to hear him preach, and he made a complete failure. He talked a few minutes, and talked very well too, then suddenly stopped and took his seat. The brethren sang another hymn, at the conclusion of which he took a new text, tried it over again, and did pretty well!" The Honorable had really taken the first performance for a failure, though, in fact the programme was carried out to the letter.

In his palmy days he was a good speaker, but his elocution is now much impaired by age and bodily infirmities. Yet he still commands the attention of his audience by the number and quality of his idem and the copiousness of his diction. But few men can make 8 more thorough analysis of a passage, draw from it more practical lessons, or discourse upon it in more elegant terms.

Sometimes he has contended earnestly with those "of the contrary part," but, in the main, he is a servant of the Lord that "doth not strive," but is "gentle unto all men, apt to teach, patient, in meekness instructing those that oppose themselves."

"By him, in strains se sweet

As angels use, the gospel whispers peace.

He 'stablishes the strong, restores the wed,

Reclaims the wanderer, binds the broken heart,

And, armed himself in panoply complete,

Of heavenly temper, furnishes with arms

Bright se his own, and trains by every rule

Of holy discipline, to glorious war,

The sacramental host of God's elect:

Are all such teachers! Would to Heaven all were!"

It is but a slight exaggeration to say of him that a man, a Christian, he is an embodiment of that charity which "suffereth long and is kind, which envieth not, vaunteth not itself, is not puffed up, doth not behave itself unseemly, seeketh not her own, is not easily provoked, thinketh no evil, rejoiceth not in iniquity but rejoiceth in the truth, beareth all things, believeth all things, hopeth all things, endureth all things." Wherever you meet him "at home, in the social circle, or in the house of his God" you meet

"The man whose heart Is warm,

Whose hands are pure, whose doctrine and whose life,

Coincident, exhibit lucid proof

That he is honest in the sacred cause."

Possessing but little worldly ambition, he has aspired, through life, to the kingdom of God and His righteousness, taking but little thought of what he should eat, what he should drink, or wherewithal he should be clothed. Hence he is one of the "poor of this world whom God bath chosen heirs of the kingdom." And now, at the age of nearly threescore, with no means of support save his hands and his head, and racked with pains superinduced by exposure and excessive mental labor, he is compelled to toil unremittingly for his daily bread. Having devoted his best days to the interests of Zion, he has reason to feel that his declining years are neglected by the brotherhood whom he loves and has faithfully served. On account of this neglect, present and past, gloom settles down upon his earthly future; but his pathway to the life to come "shineth more and more."

It is said that, to one journeying to the far North, the mysterious Aurora increases in splendor as the sunlight fades away, and that to one arrived at the open sea that surrounds the pole, the hidden sun would appear again, sweep round the horizon, and never set. Such to Elder Hoshour is the journey of life. Having crossed the bright regions within the tropics, and passed through the checkered scenes of the temperate cone, he is now plodding on through the Arctic circle, where the shadows of a long night are falling around him. But as his sun declines, shutting out from his vision the glories of this world, the light from Heaven shines with increasing splendor, revealing the brighter glories of the world to come. Soon will he reach the great Open Sea, Eternity, where his sun of life will re-appear, and run round in a circle of never-ending felicity.

-Biographical Sketches Of Pioneer Preachers, Madison Evans, pages 220-246

![]()

Brief Sketch On The Life Of Samuel K. Hoshour

Samuel Klinefelter Hoshour (1803-1883) was of German and French lineage, and as a young man was a Lutheran minister. Around 1834 he began to revise his religious views, especially those in regard to baptism. When this became apparent in his preaching it led to a break with the Lutheran Synod. He then moved to Centerville, Indiana. At this place he became actively identified with the Disciples. At Centerville, Hoshour was head of the Wayne County Seminary, holding this position for four years. He was elected a trustee of Indiana University at this time. In 1839 he became principal of the seminary in Cambridge City. He joined the Faculty of North Western Christian University in 1855 and was elected president in 1858. In 1862 he was made State Superintendent of Education. Hoshour read five languages and spoke three fluently. Among his pupils who became famous were General Lew Wallace and Governor Oliver P. Morton. Hoshour was author of a curious book entitled, Artisan Letters and edited an edition of Mosheim's Church History in 1847. His autobiography was published in 1884. In addition to his work in the classroom, Hoshour was often in demand as a preacher.

-From Hoosier Disciples, A Comprehensive History Of The Christian Churches (Disciples Of Christ) In Indiana, Henry K. Shaw, Bethany Press, c. 1966 p. 169

![]()

Hoshour, From W.T. Moore Book

![]()

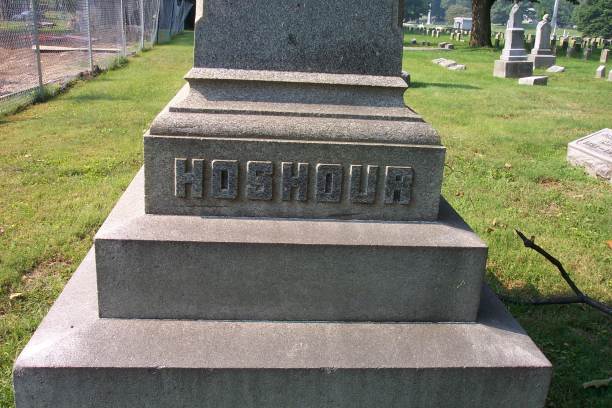

Directions To The Grave Of S.K. Hoshour

Samuel Klinefelter Hoshour is buried in the Crown Hill Cemetery, Indianapolis, Indiana. Traveling On I-65 North Out Of Downtown Indianapolis, Indiana Take The Dr. Martin Luther King Street Exit - Exit 117. (Note: If you cross White River, You Have Gone Too Far) Go North On Dr. Martin Luther King Street. Turn Right On West 32nd Street. Cemetery Will Be On Your Left. Go Until The Road Dead Ends Into Boulevard And Turn Left. There Will Be An Entrance To The Cemetery As You Cross The 34th Street Intersection. Turn Left Into The Cemetery. Lot 36, Section 9. Very close to the grave of O.P. Morton. See map of cemetery here!

GPS Coordinates

Dm.m N39° 49.051' x W86° 10.318'

or Deg.m.s. 39°49'03.1"N 86°10'19.1"W

or D.d. 39.817517, -86.171967

Grave Facing NW

Accuracy to 19ft.

Section 9, Lot 36

In 2009 - After Beautification Project

In 2003 Contruction

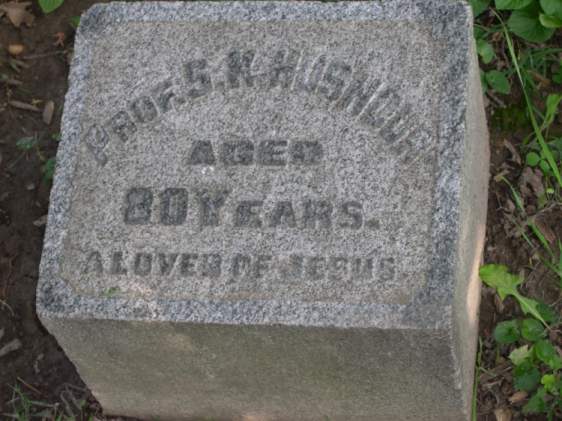

Lucinda

Wife Of

Prof. S.K. Hoshour

Aged 83 Yrs.

Asleep In Jesus

Prof. S.K. Hoshour

Aged

80 Years.

A Lover Of Jesus

![]()

Note: Special thanks is extended to Terry J. Gardner of Indianapolis, Indiana for grave photos and supplying information of the final resting place of S.K. Hoshour

![]()