The Secret Baptism Of Abraham Lincoln

Jim Martin

David Lipscomb Univerity

![]()

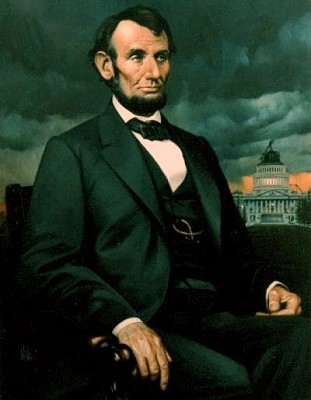

Abraham Lincoln

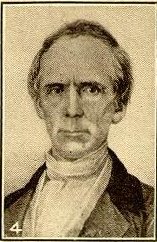

John O'Kane

Abraham Lincoln never claimed to be a member of any church, but almost every denomination makes some kind of claim to Lincoln. Starting on the “Black Easter” two days after his death, preachers began trying to demonstrate that Lincoln was a true Christian. Various ministers set out to prove Lincoln a Presbyterian, a Catholic, a Methodist, a Congregationalist, a Quaker, a Universalist, even a Spiritualist.1 (1. Cf. William E. Barton, The Soul of Abraham Lincoln (New York:George H. Doran, 1920) chap. 20; Richard N. Current, The Lincoln Nobody Knows (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1958) chap. 3; and David Donald, LincolnReconsidered (New York: Vintage, 1956) 152–53.) William Wolf labels them “shameless in claiming Lincoln as a secret member of their denomination or about to become such.”2  (2. William J. Wolf, The Almost Chosen People (Garden City: Doubleday, 1959) 26.) When the first major biography after Lincoln’s death appeared late in 1865, Josiah Holland’s Life of Abraham Lincoln, Lincoln was pictured as a “true-hearted Christian” with many “anecdotes” to adorn the theme of his religious character.3 (3.Josiah Holland, The Life of Abraham Lincoln (Springfield, MA: GurdonBill, 1866) chap. XXV.)

But Lincoln’s free-thinking law partner, William Herndon, was not buying any of it. In 1866 he began lecturing to let the world know the truth about Lincoln’s religion, or lack of it. According to Herndon, Lincoln lived an infidel and died an unbeliever.4. (4. Current, Lincoln Nobody Knows, 52. Herndon was still repeating theclaim fifteen years later. W. H. Herndon, A Card and a Correction(Springfield: Privately printed, 1882).) Newspapers and magazines throughout the country picked up the news. The fight was on, and the argument over Lincoln’s Christianity has continued through the years with such vigor that David Donald remarks, “Reminiscences on this point probably include more nonsense than can be found anywhere else in the whole tiresome mass of spurious Lincoln recollections.” 5. (5. Donald, Lincoln Reconsidered, 152.)

David Lipscomb mentions the quarrel in the July 24, 1873, Gospel Advocate:Quite an interesting discussion is going on as to whether Mr. Lincoln was a believer in the Bible and in Jesus Christ. One of his biographers, an intimate, personal friend, pretty clearly proves that he was an infidel and ridiculed the Bible and the claims of Jesus to be the Christ until the end of his life. Others present pretty conclusive evidence that he did acknowledge a change in his opinion about Christ, before his death. He often, after the forms of public rulers, expressed a reliance on God and Christ in his public proclamations &c. &c.

They argue the matter with an earnestness that indicates that they think a terrible disgrace to the Christian religion or to Mr. Lincoln or both involved in the question. 6 (6. David Lipscomb, "Mr. Lincoln and the Christian Religion,"; Gospel Advocate, July 24, 1873, 691.)

Lincoln tried to guide the nation according to Christian principles. Probably no other President every prayed so devoutly or earnestly to God. But the case for Christianity does not depend on whether or not Lincoln was a Christian. David Lipscomb's nephew, A. B. Lipscomb, reminded readers of the February 23, 1922, Gospel Advocate, “When you and I stand in the judgment before God, the questions will not be, ‘Did you follow Abraham Lincoln?’ but, ‘Did you follow God?’” 7 (7. A. B. Lipscomb, "Wherein Lincoln Was Great,"; Gospel Advocate, February 23, 1922, 170.)

Nevertheless, heirs of the Restoration Movement (Churches of Christ, Christian Churches, Disciples of Christ), like other religious groups, have wanted to call Lincoln “one of us.”

The Restoration Movement was a “back-to-the-Bible” unity movement aimed at restoring the church, worship, and practice of the NT. Early in the 1800s men like Barton W. Stone and Thomas and Alexander Campbell began urging people to leave the “sects and denominations” and unite as “Christians only.” Early mottos were “No creed but Christ” and “Let us speak where the Bible speaks and be silent where the Bible is silent.”8 (8. Homer Hailey, Attitudes and Consequences in the RestorationMovement (Marion, IN: Cogdill Foundation, 1975) 54ff.) Known variously as “ Christians,” “Disciples,” and “Churches of Christ” (and less affectionately as “New Lights,” “Stoneites,” and “Campbellites”), they emphasized a literal obedience to the Scriptures. This led, among other things, to an understanding of believer’s baptism as essential for both church membership and salvation.9 (9. Cf. Leroy Brownlow, Why I Am a Member of the Church of Christ (FortWorth: Brownlow Publishing, 1945) 94ff., 132ff.) So if Lincoln was to be a Disciple, the question was not only “Was Lincoln a Christian?” but “Was Lincoln baptized?” Sure enough, a strong tradition within the Churches of Christ suggests that he was. Church historian James DeForrest Murch, in Christians Only: A History of the Restoration Movement, discusses the belief:

There is a tradition among Illinois Disciples that John O’Kane, when state evangelist, discussed the state of Lincoln’s soul with him on several occasions; finally he was convicted and wished to be immersed. He reportedly knew that his wife, who had strong Episcopal and Presbyterian social obligations in Springfield, would be greatly embarrassed if it were known that a “Campbellite” evangelist had baptized him. But one night, Lincoln slipped away from the house with proper garments for baptism, met O’Kane and was immersed in the waters of the Sangamon River.10 (10. James DeForrest Murch, Christians Only: A History of the RestorationMovement(Cincinnati: Standard, 1962) 155.)

Although the April 1953 Discipliana states, “For more than fifty years there have been published divergent stories about Abraham Lincoln having been surreptitiously baptized by John O. Kane [sic], a Disciple preacher,”11 (11. "Presidents and Disciples: Garfield–Lincoln–Johnson, "Discipliana13 (April 1953) 2.)  the “divergent stories” as well as the “tradition” can be traced to one man, G. M. Weimer, and letters he wrote in 1942.

In the February 5, 1942, Christian Evangelist, the following letter from Weimer was published:

"I met Brother John O’Kane who was state evangelist in Illinois. It was at a convention. We were together about all the time. The Lincoln matter as to whether he [Lincoln] had ever been baptized came up. Brother O’Kane told me one day, “Yes, Brother Weimer, I know all about the affair. On the night before Lincoln was to be baptized his wife cried all night. So the matter was deferred, as she thought. But soon after Lincoln and I took extra clothing and took a buggy ride. I baptized him in a creek near Springfield, Illinois. We changed to dry clothing and returned to the city. And by his request, I placed his name on the church book. He lived and died a member of the church of Christ.”12 (12. Frederick D. Kershner, "Lincoln's Religious Status,"; Christian Evangelist, February 12, 1942, 290.)

In September that same year the Christian Review published a similar letter Weimer had written July 27, 1942. Weimer stated that O’Kane, in the presence of witnesses, said:

I took Lincoln’s confession one night at our church services in Springfield, Illinois. Then when Lincoln told his wife, she stormed the castle, and declared it with intense vehemence that she would not permit such a thing.

Well, the result was a delay. Then one day Lincoln and I went out to the creek to do some hunting. We had a change of clothes under the buggy seat. I baptized him into Christ as the Bible demands. He lived and died a member of the church of Christ.13 (13. James E. Chessor, "Lincoln's Obedience,"; Gospel Advocate, October22, 1942, 1022. Even on the face of it, this story has problems. Lincoln'sactivities in Springfield are fairly well documented, but there is no record thatLincoln attended the church of Christ in Springfield or even that John O'Kanepreached there. Louis A. Warren, "Abraham Lincoln and the Disciples,";Lincoln Lore, 675 (March 16, 1942). Lincoln didn't hunt, Ida M. Tarbell, TheLife of Abraham Lincoln (New York: McClure, Phillips, 1900) 25; andLincoln's wife was not the shrew Herndon and others made her out to be, norwas Lincoln afraid of her. Cf. David Donald, Lincoln's Herndon (New York:Alfred A. Knopf, 1948) and Ruth Painter Randall, Mary Lincoln, Biography ofa Marriage (Boston: Little, Brown, 1953).

As would be expected, both Lincoln scholars and Disciple scholars were skeptical. A typical reaction was that of Louis A. Warren, who happened to be both a Disciple and Lincoln scholar. He devoted an issue of Lincoln Lore to “Abraham Lincoln and the Disciples” and dismissed Weimer’s letter: “Mrs. Lincoln on several occasions is said to have stated that her husband never affiliated with any church and it is quite likely she knew as much about it as anyone.”14 (14. Warren, "Lincoln and the Disciples.";)

Obviously, if Lincoln was baptized secretly to avoid Mrs. Lincoln’s wrath, she would not have known about it. And even though Warren’s assessment of the situation echoed general sentiment, it was at least possible that Lincoln had indeed been baptized. Short of calling Weimer a liar, there was no real way to dispute his contention. The story was reprinted a number of times, often embellished as Murch’s account shows,15 (15. Note the additions in Murch's account above: The baptism was atnight; Lincoln slipped away to meet O'Kane; the Sangamon River is named.) and evidently believed by a large number of Christians.

Several people must have written Weimer asking for more details. Harley Patterson records his quest for additional information in the Winter 1976 Discipliana. He wrote to Weimer in February of 1942, just a few days after the original letter appeared. Weimer answered, repeating the same basic facts published in the Christian Evangelist and the Christian Review. 16 (16. Harley Patterson,"Abraham Lincoln's Religion,"; Discipliana 36(Winter 1976) 36-37.)

Recently, however, another letter of Weimer’s has come to light. This one was written to Clyde O. Summers on October 5, 1942, eight months after the original letter.17 (17.G.M. Weimer, personal letter to Clyde O. Summers. Chicago, 5 October 1942.) Currently housed in the Freed-Hardeman University Restoration Library, it reads as follows:

The statement I have about the incident of John O’Kane baptizing Abe Lincoln is not something copied from a paper or book.

When I lived in Eureka, Illinois, so my 2 boys could be in College, John O’Kane stayed with me and my family during a State convention. I asked him since he knew Lincoln very well, if he knew whether Abe Lincoln ever became a Christian. Then he said, “I am now going to tell you folks (I and wife and her father) all about the matter. I have kept it in my own memory because when he first had me to arrange to baptize him, his wife assumed a bitter resentment—that it would ruin their social status. So it was postponed for a while (10 days) till the ‘storm’ was over. Then he and I took a buggy ride one day with a change of clothing under the seat. I then baptized him in a small river near Springfield, Ill. Of course, he became a member of the Church of Christ. But I have kept it a secret as far as humans are concerned on account of his home condition. Now the possible people who might be hurt in their feelings are all or near dead. So, Bro. Weimer, I’ll tell you three folks, but keep it a secret for some years so no storm can be suffered.”

We promised. Wife and her father lie in their grave in Eureka Cemetery. I, as far as I know, am the only living messenger of the noted incident.

Took into Church

10,037. My sun is

setting. I am almost

86 years of age.

W.

Fortunately for historians (and perhaps unfortunately for G. M. Weimer) this letter offers enough additional information that at last Weimer’s reliability as a witness can be examined. (1) Weimer was eighty-five years old and at the sunset of his life when the letters were written. (2) The state convention where O’Kane supposedly revealed the secret information was in Eureka, Illinois. (3) Weimer was living in Eureka at the time so his two sons could attend college. (4) Even at the time of writing no one who could collaborate the story was still alive.

John O’Kane died January 5, 1881. Weimer, as a postscript to the Summers letter, mentions that he was “almost 86 years of age.” He obviously, then, was eighty-five at the time of writing in 1942; he would have been only twenty-four years old at the time O’Kane died—hardly old enough to have two boys in college! Furthermore, Weimer remembers the convention as being held in Eureka, Illinois. Four conventions were held in Eureka between the deaths of Abraham Lincoln and John O’Kane: 1866, 1874, 1876, and 1878. Since the last state convention that O’Kane could have attended in Eureka was in 1878, Weimer’s age at the time is pushed back three more years to twenty-one, barely old enough to have finished college himself.

Since the Summers letter comes several months after Weimer’s original letter (and presumably a fair amount of questioning), Weimer anticipates one objection by stating that since his wife and her father are dead no one can back up his story. But what about the two college boys? Weimer admits his “sun is setting.” Obviously by confusing incidents and conversations of his earlier days he has started a rumor that persists until now.

But this does not settle the matter of Lincoln’s baptism. Both Warren, in Lincoln Lore,18 (18. Warren, "Lincoln and the Disciples.";) and Murch, in Christians Only,19 (19. Murch, Christians Only, 155.) mention another story, having Lincoln baptized in Virginia while he was President. Both are inclined, as would be expected, to disbelieve it, and Warren spends several paragraphs contrasting the account with that of Weimer’s. As Warren points out,20 (20. Warren, "Lincoln and the Disciples.") this story can be traced to the January 21, 1911, Christian Standard, in an item submitted by W. R. Lowe.

The entire article reads:

W. H. Morris is one of the pioneers of the Restoration movement. He now lives in Eureka Springs, Ark. He is unable to do much work now, but his intellectual faculties seem to be unimpaired. He was well acquainted with A. Campbell, Walter Scott, and many who were associated with them in the beginning of our great work for restoration. He has traveled and preached in most of the older States, from Maine to California. He was a soldier in the Union Army from 1861 to 1865 and is a very interesting person to converse with. He told me that in 1862, while his regiment was in Washington, or just across the river in Arlington Heights, he held a protracted meeting of about two weeks, during which he baptized many of the soldiers of his regiment. Mr. Lincoln and his Cabinet attended his meeting. Mr. Lincoln and Secretary Stanton attended nearly every night and, near the close of the meeting, Mr. Lincoln came to him and said, “Morris, do you think it necessary for every person to be baptized?” He replied: “It is not a matter of think-so with me! It is a matter of revelation. Jesus said, ‘Go and teach all nations, baptizing them into the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit.’ ‘Go ye into all the world, and preach the gospel to every creature. He that believeth and is baptized shall be saved, but he that believeth not shall be damned.’ And Peter, by the Holy Spirit, said, ‘Repent, and be baptized every one of you in the name of Jesus Christ for the remission of your sins.’” When he had made these quotations from the old Book, Mr. Lincoln said: “Well, Morris, I look at this matter just as you do, and I intend to attend to it.” Bro. Morris says he thinks from what he saw that Secretary Stanton and other members of his Cabinet persuaded him to defer the matter for the time being, and he never had a favorable opportunity after that, or, at least, he never attended to it.21 (21. W. R. Lowe, "An Interesting Incident,"; Christian Standard, January 21, 1911.)

Murch and Warren seem to have misread this one. The account may or may not be true, but Lowe does not claim that Lincoln was baptized— only that he agreed with a preacher that he needed to be and that he planned to “attend to it.” If the story is true, Lincoln was certainly not the first or the last to offer that line to a gospel preacher after an appeal for baptism.

This “almost baptism” does, however, have a bearing on Weimer’s contention. After leaving Springfield for Washington, Lincoln never returned until his funeral train pulled into the station. If he had already been baptized by one Christian preacher, why would he feel a need to be baptized by another one? Surely Lincoln would not have forgotten his own baptism.

David Lipscomb was undoubtedly closer to the truth when, only seven years after Lincoln’s death, he flatly declared in the Gospel Advocate, “Mr. Lincoln never obeyed the Lord Jesus Christ or rendered that homage to him which his position demanded—never acknowledged before the world his allegiance to King Emmanuel.”22 (22. David Lipscomb, "Mr. Lincoln,"; 692.)

A. B. Lipscomb reflected the viewpoint of the early restorers in his 1922 editorial in that same paper:

Great as Lincoln was and great as his memory promises to be, the Christian will never cease to regret that he did not comply with all the simple conditions of the gospel plan of salvation as revealed in the New Testament. “If a man love me,” Jesus said, “he will keep my commandments.” This is not only the test of friendship with Christ, but of Sonship of God . . . Abraham Lincoln . . . died without ever being scripturally baptized.23 (23. A. B. Lipscomb, "Lincoln Was Great,"; 170.)

There is at least one other angle that should be explored. Lincoln, although never baptized, did have some association with the Disciples. But more has been made of this connection than the evidence warrants. Several Restoration writers seem to exhibit the tendency mentioned by Richard N. Current in The Lincoln Nobody Knows of “discovering in Lincoln the beliefs that they themselves espouse. They are prone to exaggerate these particular beliefs and to overlook or deny the rest.”24 (24. Current, Lincoln Nobody Knows, 57.)  Examples range from the recurring theme that “Many of Lincoln’s ideas concerning religion, including his aversion to human creeds . . . appear to hark back directly to Campbell and Stone . . .”25 (25. Frederick D. Kershner, "Abraham Lincoln and the Disciples,"; TheShane Quarterly 4 (April 1943) 63.) to the unsupported claim that “we can scarcely doubt that young Lincoln had an opportunity to read many, if not all, of its [Alexander Campbell’s Christian Baptist] issues. “26 (26. Ibid., 70.)

Even Lincoln’s documented association with individual Disciples is often given an exaggerated importance, perhaps to lean Lincoln toward the church.

Lincoln’s father and stepmother were Disciples. Law partner Herndon stated that Thomas Lincoln . . . united with the Christian —vulgarly called Campbellite—church in which latter faith he is supposed to have died.”27 (27. Barton, Soul, 37.)

Thomas Goodwin, the minister who preached Thomas Lincoln’s funeral, said of the President’s father, “He was a consistent member through life of the Christian Church or Church of Christ, and was as far as I know always truthful, conscientious and religious.” 28 (28. Kershner, "Lincoln and the Disciples,"; p. 65.)

Two considerations, however, must be noted. First, Thomas and Sarah Lincoln became members of the Christian Church after moving to Coles County, Illnois.29 (29. Charles L. Woodall, "Lincoln's Religion and the Disciples,";Discipliana 40 (Winter 1980) 53.) Young Abe did not accompany them to Coles County.30 (30. Benjamin P. Thomas, Abraham Lincoln: A Biography (New York: TheModern Library, 1952) 21.) Second, Lincoln was not at all close to his father. In his few written references to his father, Lincoln was both brief and apologetic.31 (31. Current, Lincoln Nobody Knows, 29.) Current writes:

There must have been a real estrangement between him and his father. He did not take the trouble to see the old man during the latter’s last illness, though it was a trip of only seventy-odd miles from his own home in Springfield to his father’s residence in Coles County. Again and again Thomas’s stepson appealed to Abraham, saying in one letter: “I hast to inform you that father is yet a Live & that is all & he Craves to See you all the time & he wants you to Come if you ar able to git hure. . . .” Abraham did not even bother to answer all the letters. He finally wrote (1851) to explain that both his own business and his wife’s sickness prevented him from visiting his father. “Say to him,” he advised his stepbrother, “that if we could meet now, it is doubtful whether it would not be more painful than pleasant; but that if it be his lot to go now, he will soon have a joyous meeting with many loved ones gone before; and where the rest of us, through the help of God, hope ere long to join them.” He did not attend the funeral. 32 (32. Ibid., 30.)

Whatever Lincoln’s feelings were toward his father, they certainly were not likely to draw him to his father’s religion.

Much has been made of Lincoln’s friendship with Edward D. Baker. Murch in Christians Only and J. M. Powell, writing in the August 27, 1959, Gospel Advocate, boast that Baker was a member of the Church of Christ and often preached.33 (33. Murch, Christians Only, 235, 132; J. M. Powell, "Col. Edward D.Baker—Friend of Lincoln,"; Gospel Advocate, August 27, 1949, 551.) Although for a time Baker and Lincoln were political rivals, they became such close friends that Lincoln named his second son after Baker.34 (34. Thomas, Lincoln, 101.) It was Baker who introduced Lincoln on the day of his inauguration as President.35 (35. Powell, "Col. Baker,"; 553.) Lincoln’s only written mention of the Disciples concerned Baker. In 1843 Baker defeated Lincoln as Sangamon County’s Whig nominee for Congress. Lincoln wrote,

There was too the strangest combination of church influence against me. Baker is a Campbellite, and therefore as I suppose, with few acceptions [sic] got all that church. My wife has some relatives in the Presbyterian and some in the Episcopal Churches, and therefore, wherever it would tell, I was set down as either the one or the other, whilst it was every where contended that no ch[r]istian ought to go for me, because I belonged to no church, was suspected of being a deist, and had talked about fighting a duel. With all these things Baker, of course had nothing to do. Nor do I complain of them. As to his own church going for him, I think that was right enough. . . .36 (36. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Vol. I (ed. Roy P. Basler;New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1953) 320.)

Baker was a dear friend of Lincoln and a Christian. But a closer look shows that he was not the kind of Christian most people would want to brag about. It seems that his primary interest in the church was the many opportunities it gave him to speak extemporaneously.37 (37. Harry C. Blair and Rebecca Tarshis, Colonel Edward D. Baker, Lincoln's Constant Ally (Portland: Oregon Historical Society, 1960) 8.) “A compulsive card gambler, Baker favored faro, especially when accompanied by champagne and oysters.”38 (38. Ibid., xi.) Tremendous law fees were paid to Baker, but he squandered them as fast as they came in.39 (39. Ibid., 68.) It was widely rumored at the time that he once received a $15,000 retainer which he lost playing faro the same night he received it.40 (40. Ibid., 68.) Concerning his religion, a highly favorable biography written less than ten years after Baker was killed in the battle of Ball’s Bluff discreetly stated:

Being naturally of an impulsive and enthusiastic temperament, he was, for a time, prompt and zealous in the discharge of his religious duties, became an able exhorter, and began to entertain serious thoughts of entering upon the work of the ministry. But as years glided by, his mind becoming occupied with politics, and feverish with the gnawings of ambition, he gradually “slipped the anchor of faith,” and was no longer seen in his accustomed place in the house of devotion.41 (41. Joseph Wallace, Sketch of the Life and Public Services of Edward D.Baker (Springfield, IL: Journal Co., 1870) 13–14.)

Three other associations Lincoln had with the Disciples amount to even less. In The Search for the Ancient Order church historian Earl I. West mentions that on his way to Washington for the inauguration, Lincoln was entertained by R.M. Bishop, mayor of Cincinnati and an elder in the church.42 (42. Earl I. West, The Search for the Ancient Order: A History of theRestoration Movement,Vol. 1, 1849-1866 (Nashville: Gospel Advocate, 1974) 323.) No doubt it was Bishop’s position as mayor rather than elder that caused the incoming President to call.

Edgar DeWitt Jones, in Lincoln and the Preachers, mentions a law partner of Edward D. Baker’s, Josephus Hewett. Hewett “organized the Christian Church in Springfield in 1832. Lincoln knew and loved Hewett, and wrote him from Congress in 1850 [sic] a letter couched in affectionate terms.”43 (43. Edgar DeWitt Jones, Lincoln and the Preachers (New York: Harper,1948) 170. The letter was written Feb. 13, 1848, Basler, 450.) One letter, however, out of the volumes Lincoln wrote, even a highly complimentary one, hardly proves that Lincoln leaned toward the Disciples.

Jones includes another story that appeared in several church papers around 1890. Lincoln reportedly ran upon one Benjamin B. Smith, a minister of Canton, Missouri, in a railway station in Springfield. Having sat in his congregation “often,” Lincoln took Smith into his office and begged from the willing preacher a private sermon from “A to Izzard.” Behind locked doors, Smith preached for a full hour, setting forth the plea the church was making to the denominations to “return to the ancient order of things.”44 (44. Jones, Lincoln and the Preachers, 75.)

Like so many other Lincoln stories, there is simply no supporting evidence that it ever took place. David Donald dismisses the tale as “most improbable” in a chapter of Lincoln Reconsidered he calls “The Folklore Lincoln.”45 (45. Donald, Lincoln Reconsidered, 152.) Probable or improbable, it is certain the sermon did not convince Lincoln to join the Disciples.

It appears then, that in spite of legends, speculations, and wishful thinking, Abraham Lincoln was not extraordinarily close to the Restoration Movement. In the only public document in which Lincoln ever gave personal testimony about his religious views, he said simply, “That I am not a member of any Christian church, is true; but I have never denied the truth of the Sciptures; and I have never spoken with intentional disrespect of religion in general, or of any denomination of Christians in particular.”46 (46. Basler, 382.) It is perhaps fitting that his handbill published in 1846 to refute the charge of “infidelity” also refutes overzealous churchmen eager to bring Lincoln into the fold.

—Jim Martin, David Lipscomb University, as appearing in Restoration Quarterly, Volume 38, No. 2

![]()