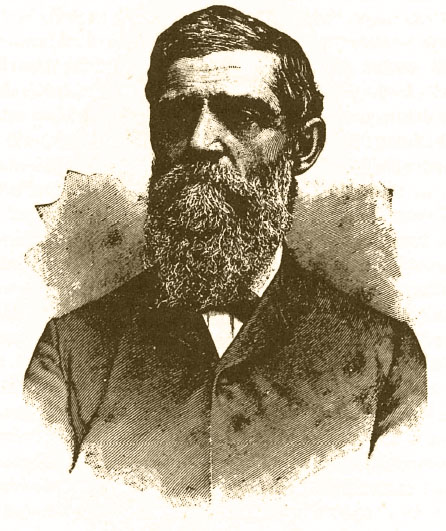

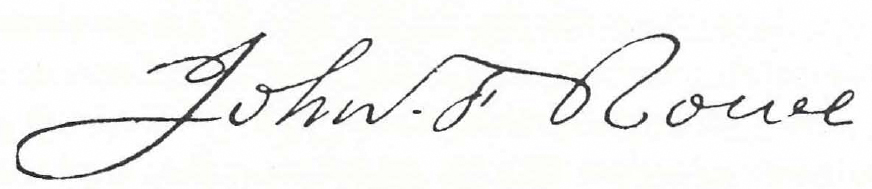

John Franklin Rowe

1827-1897

![]()

![]()

Biographical Sketch On The Life Of John F. Rowe

The American Christian Review was unquestionably the most influential paper in the brotherhood for over a quarter of a century after 1856. The editor, Ben Franklin, was, doubtlessly, the most popular preacher in the church after Alexander Campbell. For eleven years John Franklin Rowe served as an associate-editor under Franklin later to become his successor as editor of the Review. Rowe, too, founded the Christian Leader in 1886, and served as its editor until his death in 1897. Thus, through a period of intense crisis the name of John F. Rowe was often before the church. Whether his lasting influence be regarded as important or not, it is a historical fact that he played a major part in the later years of restoration movement.

Martin Rowe and his wife Martha Magdalena Alshouse Rowe were a young couple living on a farm near Greensburg, Pennsylvania in 1827. Both were of German descent; poor but industrious, and devoutly Lutheran. To them was born on March 23, that year an infant son whom they named John Franklin. In accordance to their religious beliefs the infant son was taken to the Lutheran Church nearby and "conscripted in infancy" by sprinkling.

Migration was characteristic of the times. It was a common

sight to see wagon trains pushing westward, and to hear friends and neighbors discuss moving. When, therefore, John Franklin

was only twelve years old, his family migrated into Ohio and

settled near Wooster. Here, John F. Rowe spent his childhood.

Being a farmer did not militate against his following some other

occupation as well. Martin Rowe followed the trade of a bricklayer,

and quickly taught this trade to John F. However, Rowe

informs us that when he was twenty years old, he took up the

trade of a shoemaker. This gave him a work he could perform

in the winter time when the weather made bricklaying impossible.

He worked every day from seven o'clock in the morning until

nine o'clock at night, and saved small amounts of money. During

these early years, he attended "Parrott's Academy." Educational

opportunities were limited, so Rowe read extensively and became

well informed on many subjects, especially history.

Migration was characteristic of the times. It was a common

sight to see wagon trains pushing westward, and to hear friends and neighbors discuss moving. When, therefore, John Franklin

was only twelve years old, his family migrated into Ohio and

settled near Wooster. Here, John F. Rowe spent his childhood.

Being a farmer did not militate against his following some other

occupation as well. Martin Rowe followed the trade of a bricklayer,

and quickly taught this trade to John F. However, Rowe

informs us that when he was twenty years old, he took up the

trade of a shoemaker. This gave him a work he could perform

in the winter time when the weather made bricklaying impossible.

He worked every day from seven o'clock in the morning until

nine o'clock at night, and saved small amounts of money. During

these early years, he attended "Parrott's Academy." Educational

opportunities were limited, so Rowe read extensively and became

well informed on many subjects, especially history.

The winter of 1827-28, when Rowe was twenty years old, he

first came in contact with the restoration plea. His associates

were heard to speak contemptuously of the "Campbellites," who

were then conducting a meeting at Bentley's School House. Meetings

were commonly conducted with two preachers on the ground

one to do the preaching and the other the "exhorting." Almon

B. Green, a logical and argumentative man, was the preacher, and

J. Harrison Jones was the exhorter. A man of strong emotions,

also tender and somewhat eloquent, Jones had strong persuasive

ability with the sinner. Known affectionately to his many friends

as "Uncle Harry," Jones became a close friend and adviser to

John F. Rowe in later years. It was out of curiosity that Rowe

went to the meeting at first, but soon he became interested and

obeyed the gospel.

The event changed the whole course of his

life. Jones was his constant companion, and by traveling with

heard the greatest preachers of the restoration.

Rowe gradually built up an attitude of hero-worship toward Alexander Campbell,

the "sage of Bethany." Meanwhile, his sincerity and earnestness

caused him to make friends easily. Sensing an ability in Rowe

for great service in the church, the money was raised to send

him to Bethany College.

It was September, 1850 when Rowe arrived at Bethany, carrying a letter of introduction from J. H. Jones. Rowe somewhat presumptiously took the letter to Campbell's study where he obtained his first glimpse of the famous preacher. Because there were no other chairs in the study, Campbell piled up some books for a seat and said jokingly to Rowe, "Please, Sir, take a literary seat." Jones had said to Rowe, "Tell Brother Campbell that we want him to make a man of you," and Rowe now passed on the message. Campbell replied, "That, my dear Sir, depends on the kind of material they have sent me." Rowe wilted momentarily but Campbell's simple manners soon put him at ease.1 [1 Footnote: John F. Rowe, "Reminiscences of the Restoration, No. 2," American Christian Review, Vol. XXIX, No. 18 (April 29, 1886), p. 141.]

John F. Rowe came to Bethany College with the intention of

remaining only one year, but when Campbell urged J. H. Jones

to arrange for another year, it was done. During this second

year at school, Rowe started preaching. On one of these attempts

he rode an old gray horse twelve miles, taking four hours on the

journey, to preach a sermon he had gathered from some of

Alexander Campbell's notes. After he started preaching, he

stopped only after an hour and twenty minutes and then from

pure exhaustion. When he returned home, he weighed and found

he had lost four pounds in the last twenty-four hours.

Rowe's stay at Bethany later furnished many happy memories.

Here he had heard Thomas Campbell deliver his last address,

and was later in the funeral procession that took the elder

Campbell's body up to the cemetery on the hill. At Bethany, Rowe

enjoyed the companionship of great men. Among these were T.

M. Henley, O. A. Burgess, J. S. Lamar, J. A. Meng, and J. M.

Barnes. While a college student, Rowe served as one of the

editors of the Stylus, the college paper. He was also still a student

when he married Mary Editha Pardee, daughter of Judge Allen

Pardee of Wadsworth, Ohio. The marriage occurring in September,

1852. It is not unlikely that J. H. Jones figured in this for Mary

Pardee was Jones' sister-in-law. Graduation from college came in July, 1854. John Schackleford was called "the beloved disciple;"

O. A. Burgess was the "son of thunder;" J. S. Lamar was the

"son of consolation and good hope," and J. F. Rowe held the

"pen of a ready writer."

Upon departing from Bethany, Rowe went to spend the summer

at his wife's home in Wadsworth, Ohio. That fall he became an

agent for the Ohio State Missionary Society. He spent about

five weeks, in the company of John Reed, traveling, over the

western part of the state. In the spring of 1855 he moved to

Springfield, Illinois at the invitation of W. A. Mallory, editor of

the Christian Sentinel, to be co-editor. Most of his work was

traveling in Illinois, getting subscriptions to the periodical. A

part of the time he had as his traveling companion C. D. Roberts.

Roberts was the financial agent for Alexander Campbell, who

was in Illinois buying up land for Campbell. This land later

contributed considerabiy to Campbell's wealth. These trips through

Illinois provided Rowe with a romantic life. He and Roberts

rode horseback constantly, and while hurrying across the fields

often scared up prairie chickens which looked like a thick cloud

floating away on the horizon.

During the time Rowe lived at Springfield he became acquainted

with Abe Lincoln, who was then a young lawyer in the same

town. Rowe once engaged Lincoln to try a suit for him, which

for some reason was stopped. He stayed at Springfield for two

years, and during the time encouraged the church to have Isaac

Errett conduct a meeting. Here their first child, Eugene Pardee,

was born. The Sentinel, however, was so much in debt that

Rowe could not be paid his salary, so he sold his furniture to pay

his landlord, left town, owing a note for $15.00. It was ten

years before he could pay it, and was following from state to

state with a threatening suit.

Financial difficulties followed Rowe most of his life. In 1857

he moved to Oskaloosa, Iowa, upon the invitation of A. Chatterton,

assistant editor of the Evangelist, to help raise funds to establish

Oskaloosa College. The agreement was that after the

school was financially secure, Rowe would be made a professor.

The financial depression that year crushed many men, Rowe

being among the number. He was forced to return to his work

of bricklaying for two dollars a day.

The times were hard. Northwest of Oskaloosa, lived an old preacher named Anderson, who had lost everything the winter

before except a cow and two pigs. Rowe lived here for three

days on a diet of prairie chicken and corn bread. The tame

prairie chickens lolled on a fence while Rowe picked them off with

a shotgun. Often he walked ten miles without pay to preach the

gospel. Once he was forty miles from home without a cent and

walked the whole distance. Before leaving Oskaloosa in the

spring of 1859 to return to Wadsworth, Ohio, Rowe was forced

to sell everything except his bed-clothing to pay his debts. Only

because his father sent him $50.00 could he make a return trip.

Rowe's activity during the Civil War centered in Ohio. The

summer of 1859 he worked as a bricklayer for $5.00 a day, at

the same time preaching at Manchester. At the opening of the

war, he preached in Holmesville, Ohio. It was Rowe's practice

to take no part in the war or in politics, however, he once delivered

an address to the Soldier's Aid Society. For two years he worked

as a member of the Board of the Ohio Christian Missionary

Society, but considering himself a "nonentity," he resigned. Because

he secured five thousand dollars for the Society from the

Phillips Brothers of Newcastle, Pennsylvania, the Society raised

his salary two hundred dollars a year.

G. W. N. Yost of Corry, Virginia, a wealthy man, cleared a

thousand dollars a day in the oil business. He and Rowe became

fast friends. Yost's interest in establishing a paper resulted in the creation of the Christian Standard.

Rowe never felt that he could understand Isaac Errett, so consequently,

he gave little enthusiasm to his support for the Standard.

Yost agreed to pay Rowe one hundred dollars a month as salary

for Rowe to write on any brotherhood publication. When Rowe

stated the facts to Ben Franklin, Franklin placed him on the

Review, giving him a one hundred dollar bonus to begin. After

that, Ben Franklin became John F. Rowe's idol.

It was 1867 that Rowe became connected with the American

Christian Review, a connection he retained until the close of 1886.

It is as a writer that J. F. Rowe is best remembered today.

The brotherhood had few men that could wield a pen with Rowe's

pungency and clarity. Ben Franklin certainly held this opinion

for in 1872 he wrote him:

Brother Rowe has stood side by side with us in the columns of the Review for years, as our readers can testify. We have but

few men who can write as he can; certainly not a half a dozen.2 [2 Footnote: Ben Franklin, "John F. Rowe," American Christian Review, Vol. XV,

No. 48 (November 26, 1872), p. 380.] When the Review of February 12, 1878 appeared, Rowe was listed

as the assistant editor. Franklin then said of him:

Long has he worked at our side, and well do we know how

to count on him. His pen scarcely ever slips, nor is it ever still.

Nor does he stop with writing, but he is an incessant preacher.

He is fully out now as the successful preacher and writer. We

trust the way is now open for him to be more abundantly useful

than ever before. He is ready for the work and in it. The Lord

strengthen his hands and encourage his heart.3 [3 Footnote: Ben Franklin, "John F. Rowe on the Warpath," American Christian Review, Vol. XXI, (February 12, 1878), p. 53.]

After the death of Ben Franklin, Rowe took over the editorship of the Review, Daniel Sommer wrote of him,

Critics, sharpen your pens; he is a good subject to work on.

He will neither coax nor drive into either good or bad; but convince

him, and he will go himself into whatever is right.4 [4 Footnote: Daniel Sommer, "The Present Editor," American Christian Review, Vol.

XXI, No. 48 (November 26, 1878), p. 377.]

The reader may have guessed already that John F. Rowe was

never a prominent preacher. The harsh truth is that Rowe

bordered upon a failure as a preacher. He declared that when

he came from Bethany College, he possessed a great knowledge of

the Bible which he had learned from Campbell, but lacked the

ability to organize and present it. This was true. He had deep

convictions, and a great knowledge of the Scriptures. He was

a good student, never reaching the point that he felt he had

enough sermons to retire from further study. W. O. Tomson

said of him, "As a preacher, Brother Rowe is not what many call

a pulpit orator. . . He is clear and forcible and convincing and

never fails to send conviction to every honest heart."5 [5 Footnote: W. O. Tomson, "John F. Rowe," American Christian Review, Vol. XXIII,

(June 15, 1880), p. 186.]

Shortly after the Civil War, Rowe moved to Akron, Ohio where

he lived the remainder of his life. In the fall of 1886 he became

the editor of the Christian Leader, a paper which he founded.

The last decade or more Rowe lost much prominence. It is

not too difficult to understand Rowe's thinking, and to some extent throw a mantle of charity over these years. The church passed

a period of intense trial. By 1880 the issues in the brotherhood

had, for the most part, been thoroughly discussed. Men arrayed

themselves up on the various issues, but the question that now

forced its way to the front demanding serious attention was that

of fellowship. Many had taken the position that the use of the

instrument and the missionary society were wrong, unscriptural

and sinful. But, it became evident by 1880 that many churches

were going to use the instrument and support the society anyway.

The influence of the Christian Standard, particularly throughout

the North, had been great enough to become a rallying point for

those advocating the instrument, and using the society. Whereas

one group insisted the instrument was wrong, the other insisted

it could be used. Could fellowship remain?

This question forced its way upon the church. There were

some who had formerly strictly opposed instrumental music whose

opposition subsided. J. B. Briney had stood vigorously behind

the opposition to the instrument, but now wavered. So did

Joseph Franklin, son of Ben Franklin. What happened with

these more prominent leaders happened to many less known.

Others remained loyal to old convictions. If instrumental music

were sinful, there could be no fellowship with it, and ten million

churches using it would not make it any more right than it had

ever been. A serious division was threatening and Rowe shrank

from it. He firmly believed instrumental music was wrong, but

how to continue to fellowship advocates of it was a problem the

full force of which he never met. Uncertain sounds came from

him. A small organ, he declared was permissible, just so it

was not a large one. Brethren naturally rebelled against him on the

one hand. On the other, while some congratulated him for his

liberal spirit, he was never ardently received because of his pronounced

belief against the use of the instrument. His influence,

therefore, in his last years was localized.

Rowe's death came at four o'clock in the afternoon of Wednesday,

December 29, 1897. His health prevented his being at the

Leader office since May of that year. As far back as two years

previous, he had a heavy mental strain that affected his health.

In May, 1897, he suffered a nervous breakdown. His friends

advised him to take a vacation. That August, he and his wife

went to West Virginia for a vacation and in October returned to Cincinnati. By this time he was partially paralyzed. It was

evident that he could not recover. So he returned to Akron, to

spend his last days.

Still later he partially lost his power of speech. His last

articles which appeared in the Leader through November and

December in 1897 were written under the most adverse circumstances.

He was in bed when he dictated the articles to

members of his family, who, at times, asked him several times to

repeat his statements. His last words were directed to his son,

Fred L., who still resided in Cincinnati, and who managed the

Leader in the absence of his father. Rowe said to members of

his family, "Tell Fred not to waver-keep the Leader pure and

clean." These were his last words.

The funeral was conducted at the home of his second son at one o'clock on Friday afternoon, December 31, 1897. F. M. Green, then residing at Kent, Ohio, and a close friend of the family, preached the funeral. He read the words of one of Rowe's favorite songs, "On Jordan's Stormy Banks I Stand," before preaching the sermon.

—Source: Edited from Earl I. West, The Search For The Ancient Order, Vol. 2, pages 157-164

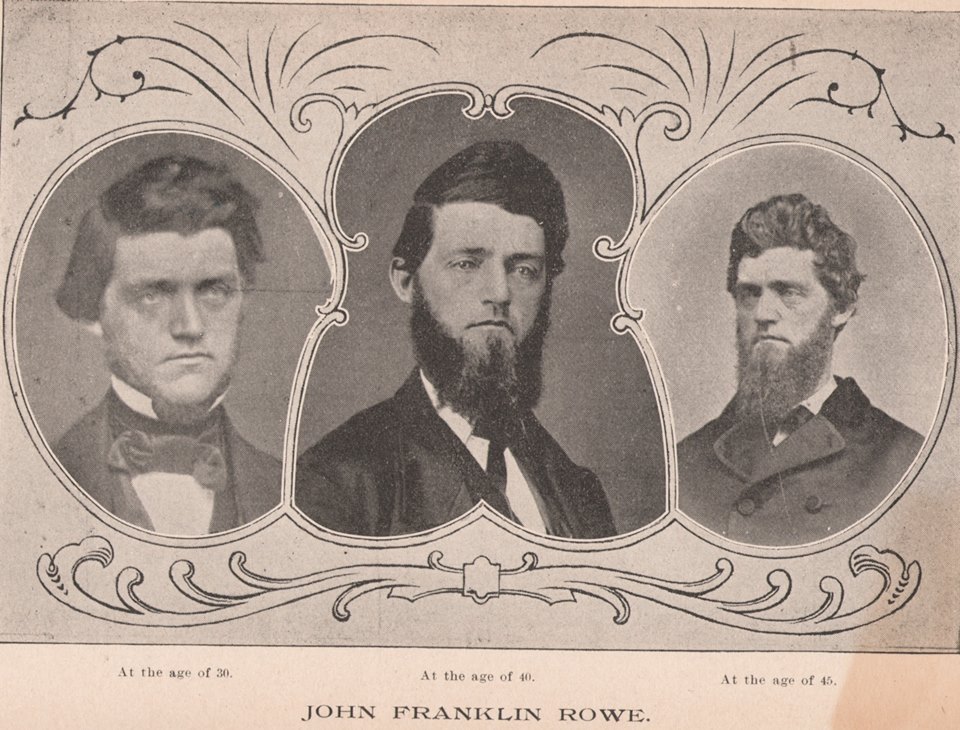

![]()

John F. Rowe At Different Times In His Life

Contributed by Terry J. Gardner - 08.23.2014

![]()

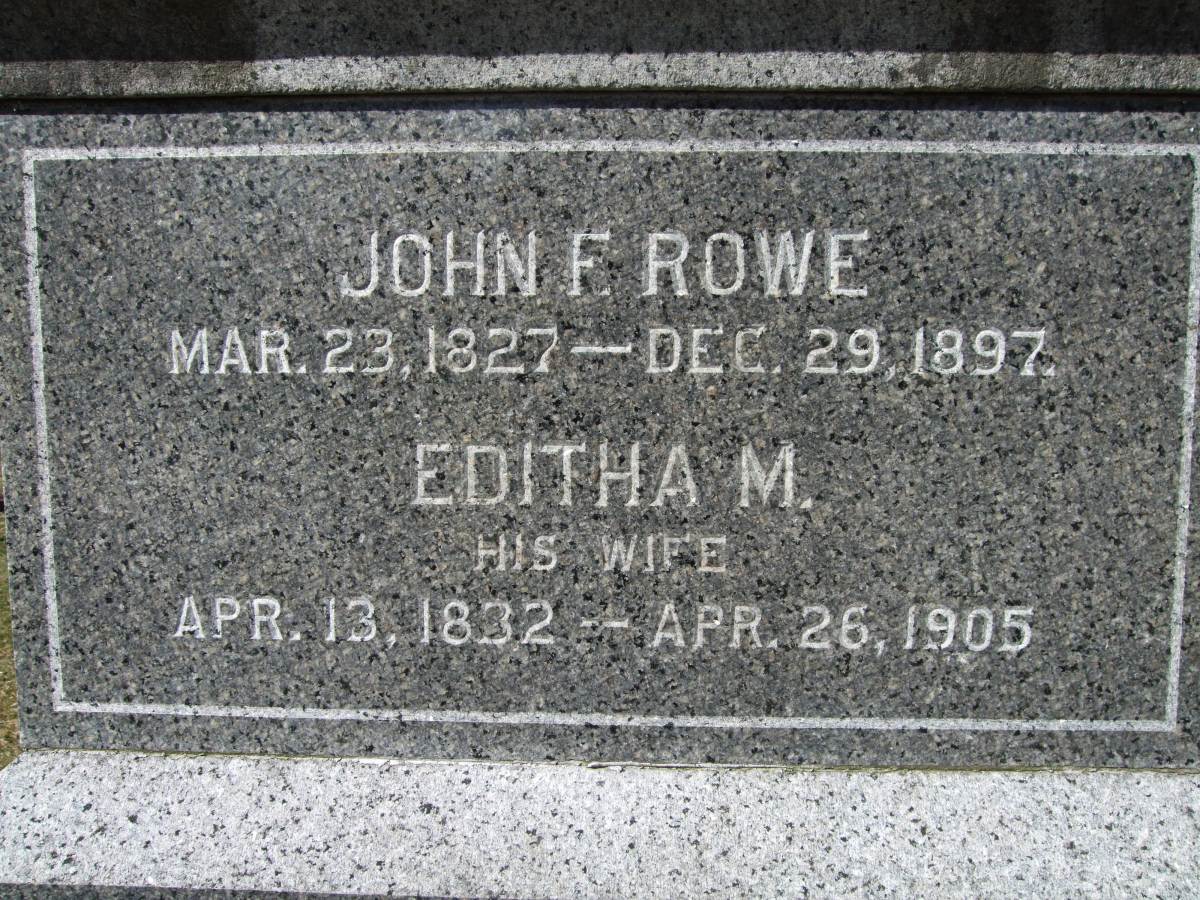

Directions To The Grave Of J. F. Rowe

The Rowe family plot is locate in Wadsworth, Ohio. Located southwest of Cleveland, and due west of Akron, is the best general description of where the family is buried. So, from Cleveland head south on I-77. At Akron take I-76 West toward Wadsworth. Take Exit 7, and head south on Hwy. 57. Turn left on Greenwich Road. The road will become College Street. Then look for the cemetery on your left. Enter the Woodlawn Cemetery to the left. Travel past the first road to the left, and continue on until you get to the flag pole. Stop the car and look toward the left, past the flagpole to the NW, and you will see the Rowe family plot. Note: If searching records you will find that though he died Dec. 29, 1897, he was not buried until the ground thawed, on March, 21, 1898.

GPS Location of the Grave

41°01'43.3"N 81°44'02.2"W

or D.d. 41.028700, -81.733950

Section 11, Lot 37 - 200

![]()

John F. Rowe

Mar. 23, 1827 - Dec. 29, 1897.

Editha M.

His Wife

Apr. 13, 1832 - Apr. 26, 1905

![]()