Rees Jones

1802-1871

[need likeness or photo]

![]()

A Gospel Preacher Arrives in Hall's Valley

One day in 1848, a pioneer preacher appeared in the area (Hall's Valley, near Trion, Georgia). He was Rees Jones of Calhoun, Tennessee, a blacksmith and one of a number of itinerant preachers who had been greatly influenced by Barton W. Stone. His message resonated in the hearts of many of the settlers, including Sewell Hall's ancestors, who soon formed a congregation.

Jones was called, "one of the first and most faithful and self-denying pioneers in the restoration of the Bible as the Will of God." (James E. Scobey, Franklin College and Its Influence, p. 11, 12. Quoted by Earl Kimbrough, "Long Legs and Short Breeches" The Alabama Restoration Journal, Vol. 1, No. 2, March, 2006, p. 15.) He was known for mistakenly telling Tolbert Fanning that he wouldn't make it as a preacher and should "go into something else." (Kimbrough, p. 15.) He was a companion of T. W. Brents' on preaching expeditions through Tennessee. Brents mentioned him in several of his reports to the Gospel Advocate. (T. W. Brents, Letter to the Gospel Advocate, "Gospel Advocate" Vol. 2, No. 12, December, 1856 p. 368. T. W. Brents, Gospel Advocate Vol. 4, No. 10, October, 1858, p. 318.) Jones wrote articles in the Gospel Advocate, including a long, complex one in July 1869 that defended the "moral influence" theory of Christ's atonement, a concept promoted by Barton W. Stone. (John Mark Hicks "What Did Christ's Sacrifice Accomplish? Atonement in Early Restorationist Thought." Inaugural Lecture at Restoration Theological Research Fellowship, Society of Biblical Literature Conference, Chicago, IL, Nov. 1994, February 25, 2005.) Brent's biographer, John B. Cowden, said that his father told him, "Reece [sic] Jones converted and baptized most of the pioneer Disciples in Middle Tennessee." Cowden added, "Reece Jones is another pioneer preacher who has dropped out of history and tradition, who should be restored." (John B. Cowden, Dr. T. W. Brents, (Nashville, Tennessee, John B. Cowden, 1961) p. 25.) He lamented that none of Jones' contemporaries wrote a biography of him.

More Information About Rees Jones

The online history of the Old Philadelphia church in Warren County, Tennessee says that Rees Jones, who first preached to Sewell's ancestors in Georgia, was an itinerant preacher who often preached there. (James A. Dillon "Old Philadelphia Church." February 25, 2004 www.therestorationmovement.com/oldphilhist.htm.) The Old Philadelphia church building is on a beautiful knoll facing the Cumberland Plateau near McMinnville, Tennessee and is a nice place to visit. Jones had a son, Isaac ("Captain") Jones, who was active in the churches and lived his last years in Manchester, Tennessee. (J. W. Grant, The Reformation History of Tennessee, unpublished in David Lipscomb University library, 1897). The Manchester, Tennessee church of Christ had information about Rees and Isaac Jones on their web page in 2006. ("Historical Brief of East Fort and East Main Street Church" March 20, 2006, http://www.mainstreetcofc.org/page2.html) The two Jones along with Jesse L. Sewell, William Davis "Pap" Carnes "are credited with initiating the work in Manchester." (http://www.mainstreetcofc.org/page2.html) Rees Jones had a sister named Eliza Fuston who was born on June 1, 1815 and died April 29, 1906. (Obituary "Eliza Fuston" Gospel Advocate, May 16, 1907, p. 319.) She said that she was not a "Campbellite" because she was a Christian long before she ever heard of Alexander Campbell.

J.D. Floyd wrote an article in the Gospel Advocate in 1911 reminiscing about Rees Jones. (J.D. Floyd "Recollections of Rees Jones" Gospel Advocate, February 9, 1911, p. 164.) He said, "A more tenderhearted man I never met. When he was in a reminiscent mood, he would speak of his early co-laborers in the gospel, while tears would chase each other rapidly down his furrowed cheek." Jones told Floyd that Gilbert Randolph, who also worked with Sewell's ancestors in Hall's Valley, had "one gift he never saw in another man. He could get up after another had preached and at once go into a warm, pathetic exhortation." Floyd said that Jones had a "warlike style of preaching" which he attributed to the hard life Jones had, and the persecution he suffered at the hands of opponents in denominations.

Jones published a short-lived paper in Shelbyville, Tennessee called the Gospel Herald with J.C. Elliot in the late 1850's, (Tolbert Fanning, "New Papers" Gospel Advocate, Vol. 6, No. 7, July, 1860, p. 218.) but Floyd said he knew of no surviving copies in 1911. He also wrote a tract on the operation of the Spirit. Floyd remembered reading it but said he knew of no surviving copies. He said, "The present generation, reading his description of the Spirit's operation in a camp-meeting revival, would regard it as a gross caricature, but the older people who were eyewitnesses of these things would see the justness of the same." (Floyd.)

Earl West mentioned Rees Jones in his book, The Life and Times of David Lipscomb. He tells of Lipscomb's visit to Calhoun, Tennessee (near Cleveland) evidently in December 1896.

"This was the hometown of old Rees Jones, one of the early Tennessee preachers that Lipscomb knew about when he was a boy. Jones was not only a preacher, but a blacksmith. Some of the brethren took Lipscomb around and showed him the blacksmith shop where Jones had worked many years before." (Earl Irven West, The Life and Times of David Lipscomb, (Delight, Arkansas Gospel Light Publishing Company, reprint 1987) p. 254.).

-Gardner Hall, April 3, 2013

Editor's Note: Special thanks to Gardner Hall for writing this article. His thrust in the article was to paint a background of restoration work done among churches of Christ in north Georgia's Hall Valley. In the process he gave a wonderful picture of the life of the great restoration preacher, Rees Jones.

![]()

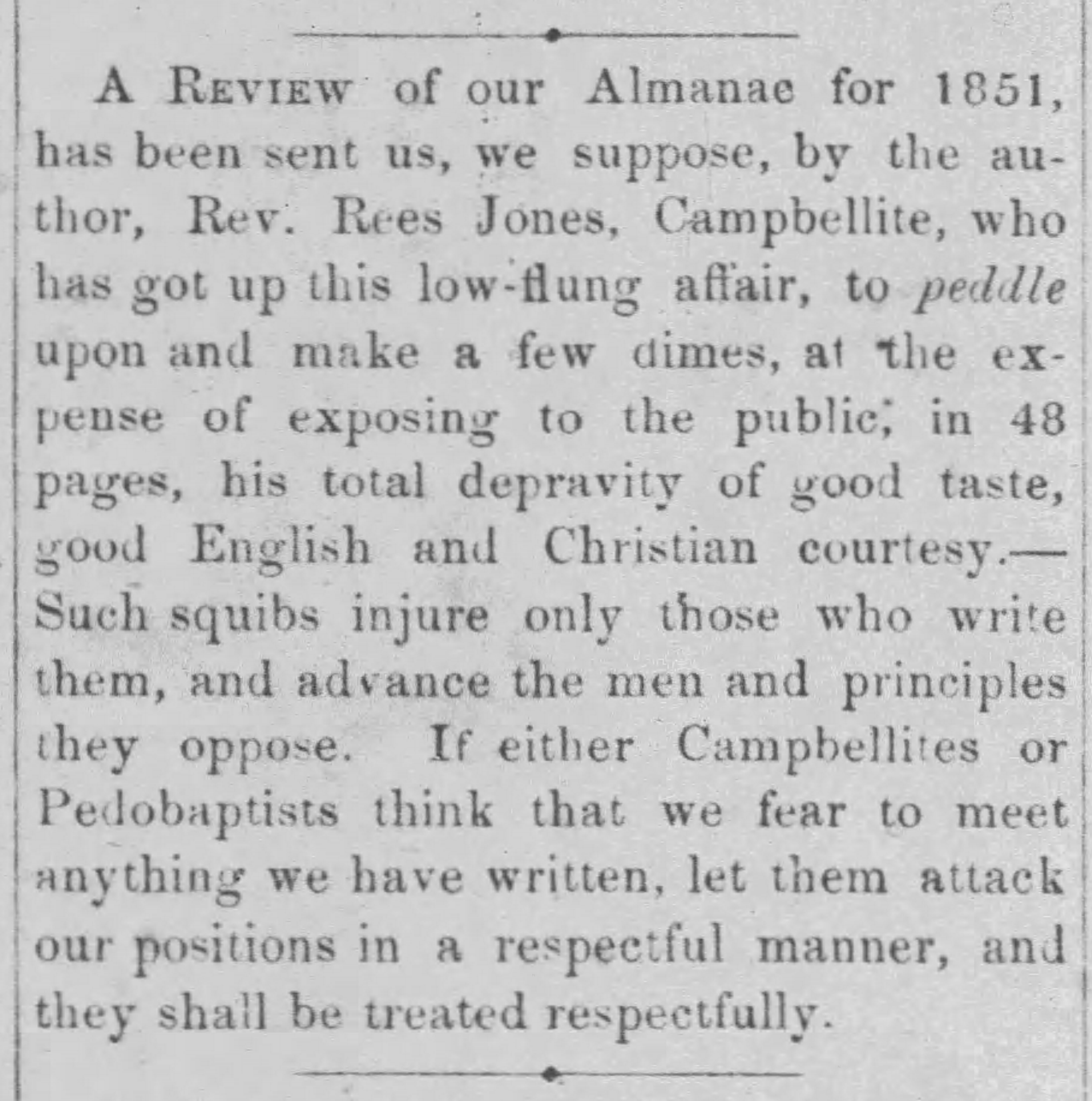

Baptist Criticism Of A Publication by Rees Jones

Tennessee Baptist, Nashville, Tennessee

Saturday, May 8,1852 p3

![]()

RECOLLECTIONS OF REES JONES.

by J. D. Floyd.

In many respects Rees Jones was a remarkable man. Soon after I became a membet' of the church, I frequently entertained him in my home. He was then an old man, and the days of his activity as a preacher were passed. By many he was regarded as a hard, unfeeling man, but this was a mistake. A more tender-hearted man I never met. When he was in a reminiscent mood, he would speak often of his early colaborers in the gospel, while tears would chase each other rapidly down his furrowed cheeks. He was strictly a reasoner, and his cold, cutting logic made him appear harsh and unfeeling. If not always, generally, men are molded by their surroundings in the formative period of their lives. This accounts for his warlike style of preaching. In his early days it was war to the knife, and the knife to the hilt. In this day of mutual recognition it is hard to realize the misrepresentation these pioneers had to meet and the persecutions they bad to endure. This kept a man all the time on his mettle. As an illustration of the spirit of the times, this incident is related: A preacher was holding a meeting in lower East Tennessee (the region where Brother Jones began his work). Quite an interest had been aroused. The opposition was fierce and unrelenting. A body of these opposers called on the preacher, when the following dialogue occurred: "We understand you came from Georgia." "I did." "We understand you ran away from there." "What if I did?" "We understand you left a wife there." "What if I did?" "We understand you stole a horse before you left there." "What if I did? What does that have to do with what I am preaching here?" Thus, without any effort on his part to contradict these charges, he went right along with his work. His friends, though, soon silenced the opposers. At one of Brother Jesse Sewell's appointments, when he was a young man, he had an addition from the Baptists. A wag, in telling of it, said: "Sewell stole one of the Baptist's sheep." From that, others took it up, and it was told far and wlde that he stole a real, fourlegged, woolly sheep. Under such circumstances it was hard for these early preachers to always be "sweet-spirited." The wonder is that these men were as mild-mannered as they were.

Rees Jones was strictly original in his methods. He

studied out the great themes of the gospel for himself, and

many a preacher o! greater note got his material from him.

He was wholly lacking in the gift of exhortation, and hence

he influenced people by reason alone. On one occasion,

when with me, he spoke of Gilbert Randolph, one of his early

companlons In labor. He said that Randolph had one gift

be never saw in any other man. He could get up after another

had preached and at once go into a warm, pathetic

exhortation. I said I did not think much of exhortation,

as it took strong argument to reach me. ''Ah," he said,

and the tears coursed down his cheek, "of all gifts I ever

coveted, it was the gift of exhortation. To see men I know

are taught and not have the power to move them to act,

it grieves me to the heart." He said he had a few times tried to exhort, but the first thing he knew he was making

an argument. My own experience as a preacher causes me now to appreciate his remark. As the seagoing vessel approaches the shore the passengers will get a glimpse of the land, and then for a time it will fade from view, to come again In clearer sight. So it is with those who are seeking for truth. It does not come into view all at once. This Is well illustrated In the early days of Rees Jones. He became s member of a church which bad no creed but the Bible and claimed no names but Bible names; yet it, like others, used the mourner's bench. Brother Jones lived at Calhoun. Tenn. He was a blacksmith by occupation. His house had large rooms. One of these was fitted up to have service in when a preacher came along. These meetings were characterized by the usual pheuomena of the mourner's bench revivals. On one occasion when there were a number of mourners and much fervor, it was noticed that Brother Jones took no part, but, on the contrary, sat in one corner of the house with his elbows on his knees and his head in his hands. Next morning, successfully, a number of the brethren went to shop, some on the pretext of having a plow sharpened, others to have a clevis mended. When the little job was done, the member would say: "Now, Brother Jones, we want to know why you acted as you did in the meeting last night." His reply, in substance, was that the whole thing was unscriptural, and that, as he had started out to do nothing in religion for which he had no scriptural authority, he could no longer engage in such work. The day was spent with much discussion and little work. From this the discussion spread to the churches in the surrounding region. At first Brother Jones stood almost alone; but he gradually won others over to his views, and the practice of calling penitents to the anxious seat was at an

end among those who claimed to be only Christians.

Rees Jones published a religious paper at Shelbyville, Tenn .. back in the fifties. lt was short-lived; but from what I learned afterwards about his ability. I am sure it was filled with thoughtful matter. As a boy I read some of the numbers, but did not have sense enough to understand what I read. I have a special fondness for old productions and would give much for a copy of that paper. After his

death a tract on the "Operation of the Spirit" was printed. I had several copies of It, but have none now. I would be glad to get one. The present generation reading his description of the Spirit's operation in a camp-meeting revival, would regard It as a gross caricature, but the older people who were eyewitnesses or these things would see the justness of the same.

-J. D. Floyd, Gospel Advocate, February 9, 1911, pages 164,165.

![]()

Reformation Gradual

When a person emerges from a dark room into the full blaze of sunlight, it is some time before he can see objects clearly. So it is when a person turns away from all tradition and humanism in religion, and decides to let his faith and practice be measured wholly by the word of God, his getting out of the one and into the other will be gradual. If he sticks close to the principle laid down, he will eventually have to give up many cherished practices of which he never dreamed.

When Luther, slowly toiling up Pilate’s stairway on his knees, thinking to secure a double indulgence, and there came to him with such force the text, “The just shall live by faith,” that he deliberately got up and walked down on his feet and resolved to be guided by what principle, he ver little thought that it would lead to a complete separation from the church in which he had been raised. Yet such was the result, but it was a long time before it was done. Thos. Campbell and those associated with him little thought when they adopted the motto, “Where the Bible speaks we speak, where it is silent we are silent,” that it would not only lead them to give up the cherished practice of infant baptism, but spring for baptism also. Still less did they think that, following this motto, mystical conversion, feelings as an evidence of pardon, and many other things, would have to be abandoned; yet such eventually was the result.

In the earlier part of the present century that fascinating system that led to the use of the mourner’s bench had thrown its weird spell around the people, and not of the church were free from it. Its ripened fruit was the jerks and other bodily exercises. While these latter manifestations dropped out, the system was held on to tenaciously. Humble and good men, such as Barton W. Stone, resolved to throw off the bondage of creeds, and all humanism in religion. And to be simply Christians. But long after this, among those who adopted this rule the mourners’ bench was still used. While now it is regarded as the property of a few of the denominations, it is in a fact that among those who claim to be only Christians in our country it once held as important place. Unless I am wrongly informed, Tolbert Fanning, in the earlier days of his ministry, assisted in the alter exercises. An aged Christian lady, who had personal knowledge of the matter, related to me how it was that while engaged in a meeting about four miles from Winchester, Tenn., he went between services and took out the alter. At the next service he told the audience what he had done, and his reasons for so doing—his rule to be guided only by the word of God had led to his action.

In Lower East Tennessee the jerks, laughing, barking, and dancing exercises prevailed to a great extent. All except a few noted exceptions of those who call themselves Christians engaged in the alter work. Among the preachers who lived in this region was Brother Reese Jones. When I first knew him he was an old man and I was but a babe in Christ. At this period he often lodged with me. The world regarded him harsh, but really he had a heart as tender as a woman. As he related the history of the conflicts of the early days in the region above mentioned, the tears would chase each other down his furrowed cheeks. His ideal preacher was Gilbert Randolph. He was a good teacher, and at the same time he was powerful in exhortation. Elder Jones said that of all gifts he ever coveted it was that of exhortation. It grieved him to see people taught, and then not be able to move them. As there were no meetinghouses open to the class of preachers to which Brother Jones belonged, he had light seats made of suitable length for his rooms. These were kept out in the yard. When a preacher came along they would be brought into the house, and services would be held there. While Brother Jones did not engage in the alter work, he had as yet, perhaps, made no open issue with his brethren about it.

One Sunday night there was a meeting of a little more fervor than usual. Quite a number of mourners were at the bench. The cries and entreaties of the mourners, the singing and exhorting of the men, and the shouting of the women, made a scene resembling a bedlam. Brother I. N. Jones, of Manchester, Tenn., now threescore and ten, was then a boy twelve years of age. The scene made a deep impression on him. He thought I was all right; and, young as he was, he felt like he ought to be among the mourners. Not seeing his father among those who were carrying on the work, he was greatly troubled. He believed his father a good man, and the work a good work, and he could not understand why his father was not a participant. Looking about, the boy at last found the father in one corner of the room, sitting on a bench with his elbows on his knees and his head in his hands, in deep thought. In this attitude he remained until the meeting was closed. Brother Jones at that time was running a blacksmith shop. Early next morning the brethren began to pour into the shop—Brother A. with a plow to be sharpened, Brother B. a clevis to be mended, Brother C. an axe to be upset, etc., etc. As each, after giving directions about his work, immediately propounded substantially the same question, it was evident that the real purpose of the trip to the shop that day was not to get the plow sharpened, the clevis mended, etc., but something entirely different. That question was, “Brother Jones, I want to know what you meant by your conduct last night?” To each one he gave the same answer: The work was not only unscriptural, but anti-scriptural; that it set aside the gospel as the power of God unto salvation, etc. The day passed with little work and much discussion. From this the fight was on, and the warfare from without was tame compared with that from his own brethren. So tenaciously did the brethren hold on to the work that it took five years to get them to abort it. For that Sunday night’s work, in that private house, started the influence that turned the brethren to scriptural methods.

In that same dwelling, J. N. Mulky preached his first sermon, while a Baptist preacher, Jesse L. Sewell, got his first idea of the proper division of the scriptures from Mulky, and was thus led into the the full light of the turret. How great the influences for good that have gone out from that house!

-J. D. Floyd, Gospel Advocate, Thursday, March 28, 1895, p. 205.

Webmaster Note: I came across this article from the life of Elder Rees Jones while researching the life of his son, I. N. Jones in January, 2025. It is an outstanding message on the struggle people endured to restore New Testament Christianity in the early days of the American Restoration Movement. If what Floyd said about I. N. Jones being 12 years of age at the time of this event, it happened in 1834.

![]()

Directions To Grave

Rees Jones is buried in Manchester, Coffee County, Tennessee in the Manchester City Cemetery. On I-24 in South Central Tennessee, the city of Manchester has three exits. Any of these can be taken, and then one can head toward town. The old cemetery is not on the main road. Get to Hwy. 41 / Murfreesboro Hwy. If heading north on 41 take a left on W. Fort St. Then, immediately turn right on N. Church St. Then left on W. High St. The cemetery will be on your right. Very close to the street in the oldest part you will find the old marker of Rees Jones. It is located just in front of a tall, maybe 5 or 6 ft. Woodman of the World marker with the name William Mahathey. The Jones monument is fading quickly.

When I found this grave, it was the second time I'd been to and through the cemetery. The first time I walked all over it and could not find it. The second time, this time in 2021, I had looked at (Find-A-Grave) and noticed someone had located and posted it. Made the second search much easier.

GPS Location

35°29'05.0"N 86°05'27.4"W

or D.d. 35.484731,-86.090931

![]()

Rees Jones

1802-1871

Milly Jones

1798-1892

![]()

Photos Taken 05.19.2021

Webpage produced 05.16.2022

Courtesy Of Scott Harp

www.TheRestorationMovement.com

![]()